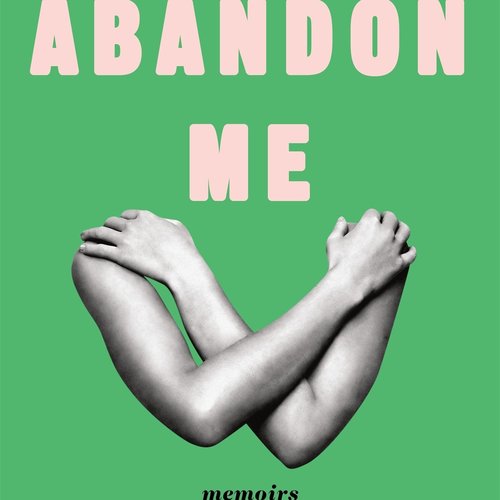

Abandon Me — Melissa Febos

Bloomsbury Publishing

February 28, 2017

The sea, once it casts its spell, holds one in its net of wonder forever.

— Jacques Yves Cousteau

The night I begin reading Abandon Me, Melissa Febos’s new collection of linked essays, I wake from a dream in which I am on a deep-sea dive gone awry. In my final moments, as my diving gear fails, I dictate an essay about drowning to an unknown presence, a presence which I can sense, but is powerless to save me. As I begin to hiccup the dark water, a voice reassures me that my dying will be quick, and I wake up before it is.

That dreams about water are really dreams about sex is a notion given by that old German master of dream semiotics, Sigmund Freud. I’d rather have dreamt of sex than death-by-drowning, frankly, but it’s no wonder I should have such a dream while reading Abandon Me. Febos’s narrator is in the midst of an explosive affair with a married woman who lives in the desert, far from her own coastal home. Early on, the pain of the distance between them reminds Febos of her childhood spent, in part, waiting for her sea captain father to return from months abroad. “When the Captain was home from sea, he woke from nightmares, screaming. When he was gone, my brother and I did. We counted time in waves… The Captain had met… storms [and] pirates. Didn’t real heroes eventually run out of happy endings?” More than twenty years later, Febos waits for her married lover, Amaia, as she “began the slow process of prying her life apart… I wanted to be strong for her but it was already hard to see a happy ending across all those miles. I waited, as I had waited all my childhood, though it never got easier.”

That Febos should love most fiercely those who were least available, invisible, or silenced by the distance of waves, geography, or prior commitments, makes sense. “How could you leave?” she writes, “I asked her again and again. There was no right answer. There was no way to prove that she would not leave again. She grew weary of trying.”

The best memoirs invite their readers into a conversation, ideally one readers are already having. When I picked up Abandon Me, I was asking myself: What is desire, and what is divine? What is romantic love, and what is holy love? And why does romantic love at its most obsessive often mimic spiritual transcendence? Why does it compel otherwise reasonable people to throw away all else for the cause of this love? Think of Romeo & Juliet. Or Tristan and Isolde. This is romance as religion. And though Febos claims in Chapter 1 that as a child she has “no god,” her obsession with Amaia, what Merriam-Webster defines as a persistent disturbing preoccupation, becomes its own kind of religion. A religion she practices with utter focus. “Nine months in love with this woman, I waited: at baggage claim in the airport, for her to call me back, to end her marriage, to promise me that she would be there. There was no distraction. I could not read. I could not write. I could not sleep. It was a despair so furious… [it] set fires… [It] was an animal.”

I was having this conversation about love with myself because two things were happening. I was writing a book about a time when I was losing my faith in the evangelical God of my youth, and also losing faith in romance. I was beginning to see the ways that I had confused divinity with desire. The ways I’d made love into a god, and God into a love. Love always required the pain of distance to really take root in me. The most significant romantic relationships of my life happened across many miles, painfully, through tears and promises. When I fell in love with Christianity, it was the same. I fell in love with what was invisible, but had been promised was on the way. In Ann Carson’s gorgeous translation of the archaic Greek poet Sappho, she describes romantic love as something which “… shook my / mind like a mountain wind falling on oak trees / you came and… cooled my mind that burned with longing.” My religious belief cooled my mind the way my long-distance lovers also did.

But like it did for me in love and in religion, distance got old for Febos’s narrator. Amaia lived near the Santa Fe desert — itself a mythic, geographical metaphor for the clash of divine and human — and in the book’s most lyrical scenes the distance between them is closed, and the affair is translated from the mind to the body. In “Leave Marks,” Febos writes, “We first made love in a hotel room in Santa Fe, where the five o’clock sun simmered on the horizon, grazing her shoulders with its fire as she knelt over my body.” What is it but worship when we kneel before a beloved like this? The answer comes quickly, not halfway through the first chapter. After Amaia received a troubling phone call, the narrator offers to read to her from Rilke’s The Book of Hours.

“The book of hours is a book of love poems to God, though Rilke was in love with a married woman when he wrote the them. So I think it must be a book about loving a woman. Maybe every desire is the desire to give ourselves away to some perfect keeper, to be known perfectly, as only a creator could know us…“

She writes, “Maybe The Book of Hours,” — and I’d say also, perhaps, Abandon Me — “is about how love makes women into gods.”

But why would Febos, a tattooed, former heroin addict and sex worker (the subject of her first memoir, Whip Smart), lose herself so completely in this affair? She hasn’t had a drink in ten years, she tells us, but this love activates something familiar in her. “I had loved before, but I had never known this mechanical insistence of my own body. It was a physical reaction absent of sense or control…” Twelve-Step recovery programs require the addict to believe in a God of their own understanding. It may be the universe, it may be a higher power, but it must replace the god that was the addictive substance. It must be a god that won’t kill you. Love without sense or control, love made into a god, is no longer love. It’s a weapon wielded most painfully on the self, but perhaps it also has the potential to deliver healing.

“When I say that I lost myself in love, I don’t mean that my lover took something from me. I betrayed myself… I mean that there was already something missing and I poured her into its place… It is true that every love is an angel of the abyss. Every lover is a destroyer. I had to be destroyed to become something else. To become more myself. But this freedom? It is worth everything.”

I’ve heard it said that memoir asks not what happened, but rather, what the f*^%* happened, and throughout Abandon Me, Febos returns again and again, in lush prose, to this question. It isn’t the answer that’s most compelling (answers seldom are). Rather, it’s the invitation Abandon Me offers the reader: to board her own ship, to hold her breath, and to leap into a dark and lyrical sea.

Melissa Febos is the author of the critically acclaimed memoir, Whip Smart (St. Martin’s Press 2010) and the recent essay collection, Abandon Me (Bloomsbury 2017). Her work has been widely anthologized and appears in publications including Tin House, Granta, The Kenyon Review, Prairie Schooner, Glamour, Guernica, Post Road, Salon, The New York Times, and elsewhere. The recipient of an MFA from Sarah Lawrence College, she is currently Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Monmouth University and MFA faculty at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA). She serves on the Board of Directors of VIDA: Women in Literary Arts, the PEN America Membership Committee, and co-curated the Manhattan reading and music series, Mixer, for nine years.Sportswear free shipping | Air Jordan 1 Retro High OG “UNC Patent” Obsidian/Blue Chill-White For Sale – Fitforhealth