[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#33999′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

One day Megi asked me how the third faerie war started, and I worried that if I gave the wrong answer, she would devour me.

A lot of our friendship was like that.

We were sitting on a picnic table near the park, our butts on the tabletop, our feet on the bench. Everywhere my body touched the table I felt like a cold plank, and everywhere I pressed against Megi was warm and melting. Our arms had been linked for at least an hour, our legs lined up ankle to thigh. I thought if anyone spotted us from far away, we would have looked like one creature, a tangle of human and faerie.

“Ummm,” I said. “The third faerie war, like all wars, had a tangled set of causes…” This sounded like the start of a bad essay for World History. “Why do you think I can tell you anything new? I’m not an expert on human-faerie relations.”

“You seem pretty advanced to me,” Megi said in a whisper that would have made the word sultry pack up and go home.

I kept my eyes in front of me. The woods were broken up by the remains of a mall. Trees sprouted off the top of a Macy’s at one end as if the store were a giant planter. The sunset raged red and purple, and Megi and I might have been the only human and faerie in the whole world watching it together. I tried not to let my worries about that spike into panic.

“Come on,” Megi said. I caught the corner of her smile without turning to face her. “Play with me.”

“What can I win?” I asked, my voice crackling over the words.

I wondered, for the billionth time, what would happen if I kissed her. Would my solemn lips cancel out Megi’s smile? Or would her smile drip into me, one slow drop at a time, until I was grinning wide?

I packed up my anger at faeries and humans and the whole broken world, packed it up tight enough that I could keep carrying it.

“I don’t remember that much about the war starting,” I lied. I remembered the exact day; I could crawl back into it, sitting in eighth grade homeroom, listening to other people stumble over the first reports, try to wrap them up in words that made sense, even if it was the worst possible kind. Attack. Invasion. Terrorism. But it wasn’t really any of those things.

I remembered the school closing, but that was later, right after the Great Planting.

“We didn’t have homework that first day.” I’d always been one of those kids who liked school, who craved books. Mostly fantasy. Megi told me that anything with faeries in it gets read at Court while everybody laughs at how wrong we got it and drinks honey spiked with whiskey and moonbeams.

Megi took an axe out of her leather shoulder bag. It had six identi-cal blades. A snowflake axe. She went to work sharpening it against her fingernails.

“It started with global warming,” I said. It felt good to be talking, even about this, because it meant I wasn’t just staring at Megi as she took me by the shoulders and turned me to face her. She had a broad face and a broad curving body. The sunset lit her edges on fire. Her garment of leaves and leather constantly shifted, as if some wind was rustling it, exposing new patches of skin. “Humans screwed up the planet so hard that it was never going to recover. And the faeries, ummm, they’d been hiding out since the Industrial Revolution. Before that, humans could talk to them, and sometimes they made out with each other.” This was starting to feel like a tangent. I circled back to the main point. “The faeries came out of hiding because the world was about to be unlivable, and taking over from the humans was pretty much the only way to save it. Well, first you tried to leave Earth, and then you came back. That’s when the battles started. Humans outnumbered faeries a thousand to one, and we still thought guns and tanks and bombs were a big deal back then.”

“And yet, here we are.” The blade sparked against Megi’s nails. “Babysitting the human species is not really fun for us, Ayla. In a few generations, if the balance is right again, I’ll get to be a seam of crystal in a rock.” Megi’s smile was so full and bright that it felt dangerous—like the kind of moon my gran always said made people do strange things. Deeds that glistened at the edges with wildness.

I looked away, toward the woods.

When I was a kid, I lived in a suburb where I had to walk half a mile to the lot behind the CVS to reach the only thing that looked like real woods. I spent hours back there finding things. Moon-colored rocks and tightly curled ferns. Scoops of dark earth or mirror-water that sat perfectly in my hands.

I wanted to ask Megi if those had been faeries, too. But she got to the asking first. “Who started the war?”

“Why do you care about this all of a sudden?” We had known each other for years and we’d never talked about what happened before we were friends. Maybe that was how we stayed friends.

“Who. Started. The. War.”

“Humans did,” I said, because that’s how I felt most days. “We started it without meaning to.”

Megi didn’t tell me if I was right or wrong. But she didn’t devour me either.

She slid down one strap of my tank top, baring my shoulder to the cool air. She trailed a finger down it. That quick, sliding motion reminded me of a single tear running down someone’s face.

And then she went to work on me. She took out a small tin of bright blue powder and spat in it. Dipping the snowflake axe into the dye, she laced the edge with color. Then she set the blade to my shoulder. Lightly.

“Humans didn’t make out with faeries,” she corrected, her whisper hitting my bare shoulder. “They made love. Long and slow and languorous.”

If talking about sex was a path in the woods, Megi was always veering onto it. Not that I didn’t think about sex. I just didn’t tellher I was thinking about it. “Sadly, we don’t do that anymore.” Her whisper was closer to my ear this time. Her breath stayed on my skin, but the words went right to my brain.

I wondered what color my face was. It probably matched the red-purple sunset. That was probably what she wanted. “Yeah,” I said. “Tragic.”

She swirled the blade against my skin.

“Why don’t do they do that anymore?” I asked. It was the first question I’d managed. Any little skitter of triumph I felt disappeared as she frowned at my shoulder and answered me with a deep, deep silence.

“Do you want to go to Court with me tonight?” she finally asked, her voice as edgy as the axe on my skin. Megi asking me to go to Court was like being invited to prom by the prettiest girl in school, and also to meet ten generations of her family at the same time.

“Is that…allowed?” I asked.

Megi clapped a hard look over her face. “It is if I want it to be.”

I looked down at my arms and found them slick with spirals—shells, or maybe galaxies. She had been painting me so I could go to Court. That had been her plan the whole time. I was probably the first human who’d been asked in at least a hundred years. “Of course I’ll go with you, Megi.”

She smiled, her face spiky with pain. “Of course.”

“What?” I hated how clumsy I was with her. It felt impossible to say the right thing. When I managed, there was this beautiful humming balance, and then somehow I would crumble it.

Megi leapt off the picnic table, and the light took hold of her hair, which was multi-colored like an autumn morning—red, brown, and the smoky blue that rose from chimneys. Her hair was also a mess, and it writhed around her shoulders as she paced. “You don’t think you can say no to me. You know I would never turn you into a tree, right?”

“It’s hard not to think about sometimes,” I muttered.

The war had started out in favor of the humans, rumbling along victory after victory, as our weapons did exactly what they were designed to do. But we forgot about magic, and desperation, and then in a single week, faeries turned ninety-five percent of the human population into oaks and birches and maples. Of course, the types of trees were different depending on which ones were native to that part of the world. Faeries would never magic someone into an invasive species. But the main point was that so many trees were now people we used to know. There was no way of being sure who had started out as a conifer and who was your old history teacher. It was smart. It kept us from cutting anybody down.

I looked out at the woods and tried to see them the way I was supposed to—as the end of some glorious era of humanity. All I could remember was the oily stomachache I got after eating McDonald’s, the hours spent filling in test bubbles, the way Mom couldn’t stop worrying about getting the best price on car insurance. “I don’t think it would be terrible to be a tree,” I whispered.

Megi ran her fingers through my hair, all the way from the roots to the messy tips, tugging gently when she reached the ends beneath my chin. “That’s why I like you, Ayla. You think about these things.”

#

My family lived inside a hill, which was better than a cave, because frankly, bats are disgusting. It wasn’t as good as a cliffside or a treetop village, but by the time we resettled, those were all taken.

Mom had gone out, probably tracking a deer or something, but Dad was in the kitchen stabbing at his dead calculator. The batteries had been out of juice for over a year, but he still tried it every day. He was adding up columns of numbers he’d carved into the table with a tiny knife. Before the third faerie war, Dad was an accountant. He thought that staying an accountant made him a rebel. I thought it made him sad and a little bit squinty.

I passed through the earth-walled room, picking up a candle on the way. It would be dark soon, and I wanted to see as well as I could while I got dressed in the little nook we called my room. “Going out,” I said.

Dad didn’t look up from his dead slab of plastic. “With Rob? Gustavo?”

I made a noise that wasn’t a yes or a no. Sort of a hmhmpfh.

Let Dad think I was going on a date and repopulating the earth.

He had told me once that it was my rebel destiny to have babies. Lots and lots of human babies. Mom didn’t care about rising up—she just wanted to live a quiet life as far away from the faeries as she could get. They had turned her parents and brother and nieces and nephew into Douglas firs. She didn’t like Christmas anymore. She said that the overlap of good memories and bad ones made her brain swirl.

“I’ll be back before dawn,” I said.

“Good,” Dad said. “Sounds good.” Then he threw the calculator at the dirt wall and a clod of dirt exploded.

With no school to take attendance and no phones to check up on us, it was shockingly easy to sneak around with Megi. Most of the teenagers I knew were taking full advantage of this in their own ways—they just weren’t spending time with faeries.

I wanted to explain to Dad that I’d tried to hang out with humans. And then Megi showed up at my elbow one day, bright and chattering. She looked more nervous than I felt, worries writhing on her face like freshly caught fish. I liked that I could see exactly what she was feeling, even when it was bad. I liked that my own feelings doubled, then tripled, as I walked next to her through the quiet woods.

Within an hour, she’d told me that she was an outcast among the faeries. “I’m pretty much reviled.”

“Why?” I asked, way too fascinated.

“Oh, you know, I think we should be making some kind of patch-work future with the humans.”

“I would sleep under that quilt,” I said. “But it might give me weird dreams.”

Her wide lips split into a grin, and then she laughed, and the earth under our feet cracked slightly. I stepped back, almost ran into a tree, and then whirled around to apologize to the person who was probably trapped inside. “Sorry, sorry,” I said, backing away from the trunk.

When I looked back at Megi, she was staring at the ground. Right where her laugh had fallen, a starry white patch of Queen Anne’s lace had burst into flower.

I was down on my knees as quickly as Megi. She studied the flowers intently. I’d never seen a faerie actually use magic before, and it made breathing feel new and complicated. She pinched her fingers and ran them up the stem of a flower, and I wondered if any human would have felt their blood sliding around in response, or if that was just me. Then she plucked the flower and was leaning forward to slide it behind my ear before I could even think about how close that put us.

Her body, my space.

Her frown, my smile.

“No one has ever made me laugh before,” she said, her lips offset with mine, but only slightly. If I pressed forward an inch, and then another, I would catch the edge of her mouth with mine.

“You mean… today?” I asked.

“I mean ever,” she said.

“I wasn’t alive for most of ever,” I said. “But if I’m the funniest thing so far, it must have been grim.”

She laughed again, and the ground beneath us grew snowy with white flowers.

“Aren’t faeries clever?” I asked. “They must laugh all the time.”

“Clever and funny aren’t the same thing,” Megi said. “One is all about amusing yourself, it’s a sort of trinket for your brain to play with. Faeries are very fond of trinkets. They’re less interested in jokes.”

“I’m not a stand-up comedian or anything,” I said, which felt strange as soon as it came out of my mouth. That profession had gone extinct.

Megi ran one hand down her throat. “I can’t laugh unless I’m in this body, and it feels so strange.”

It didn’t look strange to me. It looked glorious. Maybe that wasn’t how it felt from the inside, though. She twirled a piece of her hair around her fi nger, tighter and tighter, until a curl of smoke spiraled into the air. I snatched her hand away.

“Sorry,” she said.

“It’s okay,” I said, even though my fingers were throbbing. A blister rose where I’d touched her. “Only you can prevent forest fires,” I muttered.She didn’t laugh at that one. Too human, I guess.

Megi looked at my bright red hand. “You’ll never speak to me again,” she intoned, each word like dire prophecy. I must have given her what my mother calls A Look, because she added, “None of the other humans will speak to me more than once.”

“Maybe I can help with that,” I said, even though most humans barely talked to me.

“Maaaaybe,” Megi said, the word flaring with possibility. “Or it could just be you and me for a while.”

I nodded a little too eagerly.

After that, Megi showed up a few times a month, only when I was alone. She never had to tell me we were a secret. Until today, I thought we would stay a secret forever.

#

When I left the hill currently known as home, electric blue dusk had already fallen. It saturated me fast. I wondered if it made me look slightly more magical in my best shorts and a shirt made of scraps from the shirts I’d outgrown, sewed back together. Going to Faerie Court probably required something better, finer, more enchanted, but this was all I had.

I stood in the nearest moon-brushed field and waited. Megi loved entrances. I loved watching them. This time she floated in on a sort of armchair made of clouds, wearing a cobweb dress that didn’t cover much.

Megi was young for a faerie, which meant she had been around for only a hundred years. But she hadn’t been alive in the human sense. Most of that time had been spent as a rock at the bottom of a river, a grain of sand off the coast of Maine, a white dwarf star. So many nights, she’d laid on the ground, our heads touching, our bodies pointed in opposite directions. She told me about the few times she’d been in a human body, to dance in honeysuckle rain or to test what a storm felt like against her skin. I loved all of her stories, except for the star ones. They were too lonely for me. When she told them, I ached cold for hours.

“Oh,” she said, running her hand down the veinwork of my shirt. “All of your seams are on the outside.”

“Is that a bad thing?” I asked, shivering.

“It’s an Ayla thing,” she said. Which didn’t really answer my question.

She stepped down from the cloud chair, patted it like an obedient dog, and it dissolved. She offered me her arm, and I noticed that her arms and legs were painted with the swirls she had put on me, except hers were shimmering green to go with my blue.

Megi led me into the woods. We walked through the woodsy silence, which is actually full of sounds—cracking branches and tree whispers and insects trying to hook up.

“Watch this,” Megi said. I turned to face her. She held up her thumb and forefinger and rubbed them together. A blue-green wisp rose from her fingertips. I heard the small but satisfying crack of a nutshell coming apart.

“What was that?” I asked.

“A second,” Megi said. “It was closed up tight, so I opened it. I wanted to feel like we had more time together, just the two of us, before we got to Court.”

I nodded, secretly thrilled. I tightened my arm around hers. She smelled like the world’s best apple cider, sharp and sweet with twelve distracting spices. I wanted as much time with her as I could get. And then I thought—maybe she was just afraid of what would happen when we made it to Court. Maybe I should be more afraid.

I followed Megi further into the forest. In a little while, we came to a clearing with a shiny hill in the center, pushing up toward the canopy. I walked over to it and slid my fingers along the metal. It was as warm as skin, etched with the sort of markings Megi had put on our arms. She opened a door that I never would have noticed, and fog rolled out. I stepped back to get a better look at the whole thing.

“Faerie spaceship?” I asked, to be one hundred percent sure.

“Faerie spaceship,” Megi confirmed. She shrugged like it was no big deal. “They make great ballrooms.”

I had always wanted to see one of these up close. The year when I was thirteen, the planet was ringed with faerie spaceships. We wasted a lot of time thinking it was an alien invasion. The humans had never considered that there may have been creatures on our own planet that were highly intelligent and also highly interested in escaping our mess. In the end they came back, though. Megi told me they couldn’t stand being away from everything they had loved for so long.

#

Inside the spaceship, the faeries were brilliant and gorgeous and perfect and everywhere. It was like staring into a kaleidoscope that had come to life. I had to blink a lot and rub my eyes. The whole body of the ship was curved and open, filled with hanging plants that had long spiky tendrils and didn’t need soil to grow. The floor was covered with earthy-colored tiles in organic shapes that fitted together snugly.

“Do you want something to eat?” Megi asked, turning us toward a room that seemed to be a dedicated feasting area. There were tables heaped with roasted meat, shining fruit, oozing honeycomb. I thought I saw someone biting into a live peacock. Megi shook her head, the exact same way I would if I took her home and Dad did something embarrassing, like showing her his calculator. “Let me get you a drink,” she said. “I would stay away from the moonbrew. But everything else should be safe.”

“I don’t think any of this is safe,” I whispered.

Megi stared at me. Sometimes it felt like her stare could slice through me without any help from an axe. “Do you want to dance?”

“Ummmm,” I said. “Okay.”

Yes, I meant. Yes.

I had gotten so good at hiding the truth, or maybe just the magnitude of it. Megi would press herself close to me some days, but the next time I saw her, she would be as distant as a long-dead star. I thought if she knew, if she felt what I wanted, I would blink twice and she’d be gone.

Megi pulled me out to the center of the floor, which was also the center of the ship. I took a single nervous breath before the music started. The band stood above us on a little platform, clutching instruments I knew—fiddles, flutes, guitars. I wondered if we had stolen those from the faeries, or if they had stolen a few things from us.

Megi nodded to me as the dance started, and I nodded back. The fiddle slurred high and lonely. When the drums leapt in, we stomped and spun and clapped so fast that the room sounded like rain.

I knew the steps. I could feel them without thinking.

“Hey!” I yelled as I spun with Megi. “Did you implant these dances in my head?”

“I can’t do that,” she said. “You’re not mine to touch.”

I heard someone laugh, high-pitched and shattering. It didn’t sound anything like Megi’s laugh. She and I twisted and swam and touched each other’s waists with little darts of our hands.

“How do I know how to do this?” I asked.

Megi yelled, “You’ve always known.”

My feet worked faster, heels tapping strange rhythms. The dance formation broke, and other faeries passed me in and out of their arms, as strong as metal bars and supple as spring branches. I fought my way back to Megi.

“You’re not telling me I’m a faerie, right?” I whispered.

“Some things have always been inside of you,” she said, “waiting in your cells, caught in the spirals of a helix.” She traced the lines she’d painted on my shoulder. “It’s one of the reasons humans and faeries keep separate. Even in the old stories they were never together for more than a minute, an hour, a carefully bounded set of days.” Her voice threaded itself into the song—I didn’t hear them as two separate things. “You and I are more alike than we are different. They don’t want us to remember that.”

“Why not?” I asked. “Faeries don’t want humans on their genetic turf?”

“No.” Megi’s hands found my waist. “We know that we can cross a line, too. Become more human.”

The room split into a formation I didn’t know, everyone stream-ing as Megi and I stayed put. There were wicked smiles, stony faces, moving fast. And then the faeries whirled into place, as if this had always been part of the dance. A circle formed around us, weapons pointed inward like a mouth full of sharp, mismatched teeth.

Some of the things they were brandishing looked like thorns grown long enough to be daggers. Others were staffs made of moonglow, hooks carved from silvery ice. No snowflake axes, though. That must have been Megi’s special thing.

“Thank you for having me,” I said. “Now I’ll just…go.” I resisted the urge to back away, because there were pointy objects behind me. I spun around, but the door that had allowed me into the Faerie Court had vanished back into the seamless metal walls.

One of the faeries stepped forward and took Megi’s chin in her hand. She forced Megi’s face toward me. “What will you do? Turn her into a sapling and plant her in your courtyard? You can make love in her shade. The human will have to watch it until she withers.”

The faeries laughed and laughed, and the sound was so cold that ice crystals splayed across Megi’s cheeks.

“Is that why you brought me?” I asked in a crumbling voice.

The faeries laughed harder.

Was that the point of all this—was I Megi’s human weakness? Did she bring me to the Faerie Court to come clean?

“That’s not what I want,” Megi said, and I knew from the look on her face that she wasn’t lying. But that didn’t mean we were out of the woods. The faeries pressed in tighter. The points of their weapons paled in comparison to the stab of anger in their eyes. My heart froze and then melted, and the feelings I had for Megi, the feelings I’d been holding back for over a year, finally spilled out.

I cried. The spaceship cracked at the seams as the sky above us poured stars. The faeries gasped and screeched, their voices tearing at the night. My blurry vision swam all the way to Megi. She was crying, too—a single tear dropping off the cliff of her high-boned cheek. But it didn’t do anything. It didn’t change anything.

She was just a girl leaking saltwater.

Megi looked into my eyes and for the first time I didn’t worry if they were pretty enough. I wasn’t afraid of saying something stupid. But I was afraid.

So was she. I had never noticed it.

“Tell me about the third faerie war,” she said, thickly, urgently.

I could see what she was doing now—what she was desperate for. Megi wanted me to remind her that we were enemies. But I didn’t want to, and the not-wanting was so deep and heavy that I became immovable. The moment flowed around us. I was a rock at the bottom of a river.

And then we took a breath at the same time, to the exact same depth, a sort of music that we both knew, and when we exhaled the entire court was gone. Megi and I were sitting on the cold dirt of a bare hill, our legs splayed out in front of us. The only proof that the Faerie Court had been there a moment before was the char of roasted meat and a final strain of music.

“They’re not coming back, are they?” I asked.

Megi shook her head.

“I can’t…I can’t bring you home.”

Megi nodded. She already knew that.

“What do we do now?” I asked.

Megi pulled me closer, until we were as close as two people could possibly get, until our skin ran together like rivers. I closed my eyes—the darkness behind them was warm and ripe. She kissed me, and it tasted like salt and skin. I kissed her back, and it tasted like honey and cold stars.

We left the dark mound where the court used to be, the galaxies on our arms pressed together, our faces close enough for whispering. We didn’t care about being quiet, though. We laughed our defiance until I felt sure that humans could hear it, miles away in their hills, living inside of their new tree-bodies. Megi rubbed her fingers together and with a wisp of blue-green, another second split apart.

We found a perfect spot in the woods. And then we devoured each other.

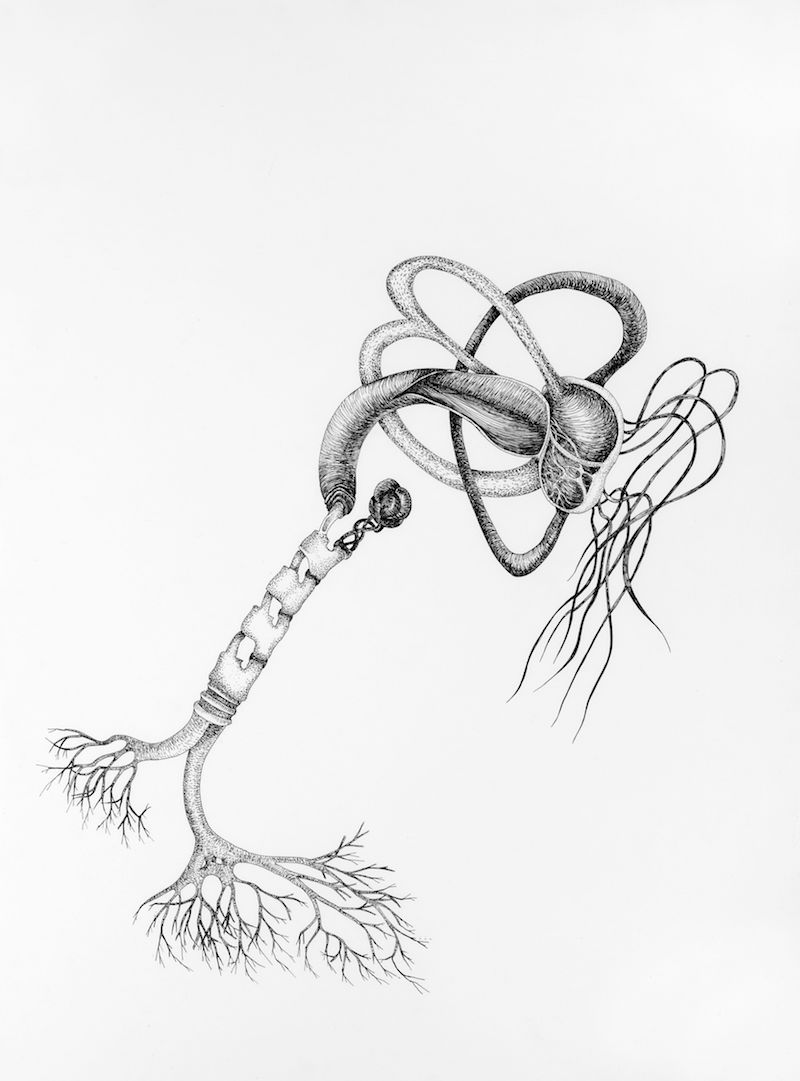

Art by Maggie Nowinski.

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#33999′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

[av_one_half first]

[/av_one_half]

[av_one_half]Amy Rose Capetta is an alum of the Writing for Children and Young Adults program at VCFA. She is the author of three YA novels, most recently ECHO AFTER ECHO, a queer love story wrapped in a murder mystery set on Broadway. Her five forthcoming novels all feature queerness and magic, from an Italian-inspired fantasy (THE BRILLIANT DEATH) to a gender bent Arthurian space fantasy (ONCE AND FUTURE) co-authored with the scoundrel of her heart, Cori McCarthy. Amy Rose lives in Vermont.[/av_one_half]

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#33999′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]Nike air jordan Sneakers | Trending