[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#33999′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

There is a crush of Storm Troopers, Men of Steel, and Optimus Primes milling around the cavernous confines of the Javits Center. Surrounded by freaks and geeks, Astrid Atangana wonders how she and her friends—the self-styled Nyanga Girlz—come across to the Comic Con crowd. Mbola, rocking grills and street gear, calling herself “Fly Girl: Superman’s dope-ass cousin from the hood;” Mimi, in the Psylocke cosplay costume, pre-ordered from China a full month in advance; and her, a too tall black girl in a too short red kimono. Wearing bifocals, no less. She takes off her glasses. She cringes, thinking about the Princeton admissions letter, secreted away in a notebook, in the far reaches of her knapsack, then secures the bag’s straps, along with the side slung holster of her katana, for what feels like the kajillionth time.

“Batman has a nice booty,” Mimi opines, twirling an eely, purple hair strand that slithers and coils around her index finger. Her flinty eyes are fixated. Medusan, Astrid thinks, filled with equal parts fascination and disgust, watching her friend watching yet another guy.

“Which Batman?” Mbola asks. “There are like a billion Dark Knight wannabes up in this piece.”

Mimi is jerking her head to their left, whispering rapid-fire, “It’s the retro, Adam West-y one, over there, over by the Halo booth,” then loudly, “Oh my God, Astrid! Don’t look right at him.”

Astrid is already looking right at him. Staring, in fact. Mbola rolls her eyes in exasperation, yet all too soon she is staring too. Batman catches their gaze and gives them all an even-toothed, Tic Tac grin. Mimi denies him a smile. Instead she turns away, flips her synthetic tresses, then tosses him a knowing, coquettish look over her shoulder. Classic Mimi. Astrid hopes he’s worth it; hopes she gets a bang for her buck. The girl spent two weeks’ worth of pay to buy her wig—its shock of violet locks had to be the exact shade of purple as her costume; the cheapo wigs at the beauty supply in the West Orange mall where they all worked were deemed insufficiently “Con-worthy.”

A schlubby, East Asian Boy Wonder sidles over and palms Batman’s left butt cheek, his lingering hand partially obscured by a waterfall of midnight blue polyester. Manhandling, Astrid thinks, her brain continuing a week-long streak of randomly churning out “M” words, morphing her into some Tourette tic-ish freak. It was weird but strangely familiar, like the month after their class trip to see Hamilton on Broadway when quotidian conversations tempted her to segue into song. That month, talk of Batman’s heinie might have triggered wordless humming of Sir Mix-a-Lot’s ’90s throwback hit “Baby Got Back” under her breath. Or at least some bars from the Nicki Minaj remix.

Mimi is glaring at the Dynamic Duo now. “Look Astrid. It’s one of your fairy tale up-the-rear endings.”

Mbola sniggers her approval of the diss.

Maleficents, Astrid thinks. She mentally kicks herself, again, for ever, EVER sharing her slash fan-fiction with these so-called friends. For months, they had cracked on her about Luke Skywalker letting Han Solo stroke his light saber during long and lonely desert nights on “Brokeback Tatooine.” She had almost given up on writing before she met Young Yoon at the comic book store. He was the one—the only one—who hadn’t laughed. Instead, he had pulled out a sketchpad and shown her his storyboards, shared panel upon panel of darkly rendered swordplay. The only text was his name in Hangul: 영윤. They’re pretty much just mimes right now. I need someone to give them a voice. Can you help with that, Astrid? And Astrid, knowing what it was like to be kept mute, had said yes. He was upstairs right now, manning their spot in artists’ alley. The one they had spent months scrap-ing together funds for in hopes that they could really make a go of all this.

Silently, Astrid packs up her ever-growing collection of Jetstream uni-ball pens, her glasses, and finally her notebook, its pages full of secret letters, story scribblings, and haiku descriptions of pass-ersby: Rotund Robin comes/Caped Crusader smiles, grateful/ Their night play begins.

“Where you goin’?” Mimi demands.

“The booth,” says Astrid. A misnomer really, it was just a table they were sharing with some other dude hawking a cheesy, bootleg comic about homicidal bees called Stinger.

“Yeah, tell the booth I said hi,” Mbola says, then turns to Mimi. “’cause that booth is fine as shit.”

Mbola has a crush on Young Yoon. An insistent one. She thinks he looks like Night—the humanoid robot cum heartthrob from her fave Japanese soap opera, Zettai Kareshi. She also thinks Astrid is secretly dating him. She is a dim bulb: her belief in Astrid’s fre-quent assertions that they are “just friends” flickers off, and on, and off again, fickly.

“You hear me, Astrid?” asks Mbola. “I said tell Young Money I said ‘make that paper.’ Get that shmoney. Get it. Get it.” She’s dancing and dipping low as she chants the last of it. Laughter wild, feral.

“Shut up, Mbola.” Mimi commands. “Come on Astrid . . . don’t get mad, girl. You promised. The panel, remember? The open buffet of K-town hotties.”

The panel that afternoon featured stars from Boys Over Flowers, Mimi’s fave Korean soap. Astrid was supposed to be Mimi’s Rosetta Stone wing-woman, pulling guys with the few Korean phrases Young had taught her. Simple stuff, really, like ‘hello,’ annyeong and ‘goodbye,’ annyeong.

“Annyeong,” Astrid says, fidgeting with her katana strap, looking at the growing frown on Mimi’s face. “I’ll be back. Just going to check in, see if we sold anything.”

She doesn’t want to come back, doesn’t want to return to the cutting laughter and faux camaraderie of these frenemies, but she knows she will. She is “Elasti-Girl,” (cue sad trombones) bending and contorting to the will of others in a single fold. She hates this about herself, knowing that she will give up all this comic book mishegoss and cave under seismic maternal pressures to head off to an Ivy far, far away, leaving Young in the way more experienced hands of Mbola. It doesn’t take x-ray vision to see this. But for now, in this fantasy land, nothing is decided. She is surrounded by mild-mannered accountants, data entry specialists, computer analysts—all shedding their daytime skins. They thrill to their secret identities in a dreamscape free from the mundanities of rumored downsizings, late mortgage payments, and vacant relationships. For a brief time, they all are heroes. Her too.

#

That morning, Astrid had marveled at the surprising ease of her escape from home. As strongholds go, the Atangana household is rather well fortified, its days regimented by a rigorously upheld agenda of activities sanctioned by her mother. The totemic family calendar marks them all: “Saturday, October 27, 10am-2pm: Mrs. Atangana—church dinner planning meeting // Mr. Atangana—golf with colleagues at Fairlawn // Astrid—college prep with M.F.” M.F. is Mimi, with whom she is supposedly prepping for next week’s college campus tour. As alibis go, Mimi is pretty ideal. She is a play-cousin, from a suitable Cameroonian family that attends the same church as her own and who, above all, possesses the same immigrant values: education and hard work. The Forjindams own a similar beige-painted-by-numbers, prefab mansion a few blocks away from the Atanganas. Both families stoically take their steep suburban tax lumps so that their kids can grow up in nice homes, with really nice neighbors and even nicer school districts.

Mimi never makes straight As like Astrid in said schools, but she does sing in their church’s youth choir, the ultimate imprimatur of a “good girl.” With a thrill, Astrid sometimes likes to imagine the look on her mother’s face if she ever found out that Mimi had had her purity ring resized so she could slip it off effortlessly when she went out on dates. She knows what her mother’s face looks like around Mbola already: the upturned nose, the repeated sniffing. Mbola is a distant relative of the Forjindams. She lives in East Orange, the bizarro West Orange, where her asylum-seeker parents braid hair, tend other people’s lawns, and receive ill-con-sidered hand-me-downs and hand-outs from their West Orange kin. Even further removed from making straight A’s than Mimi, Mbola teases Astrid for “talking white” and attends a crowded high school with metal detectors and girls named after luxury cars and liqueurs like Alizé or Lexus. Astrid’s mother thinks Mbola is an unsavory influence. “Unsavory” like corrupt food left too long on a countertop.

“…And make sure you remind Mrs. Forjindam to bring her okra stew to the church dinner this Sunday, Astrid,” said her mother that morning, cleaving through the family room and its stuffy coterie of plastic-covered couches on her way to the garage. Astrid, her proximity alert blinking rapidly, had hurried in from the kitchen, only three steps behind the hull of her mother’s retreating form.

“Astrid! See me trouble, oh. Where is that girl?” Her mother had stopped, mid-stride, suddenly sensing that perhaps she hadn’t been automatically attended to.

“I’m here, Mummy,” Astrid said.

“Yes, you are. Don’t forget what I told you about the dinner,” said her mother, charging forward once more. Into the garage, then hiking up into her towering Benz M-Class; her mother ticked through her checklist: put dishes in washer, Astrid (garage remote in hand, slow mechanized garage door lifting with the creak of an outdated android), call your grandmother, Astrid (keys turn in the ignition, the craft readies for departure).

“Yes, Mummy,” said Astrid, then again, “yes, Mummy.” The last said to empty air. Her mother had finally taken off.

#

On the PATH train platform into the city, Young, Mimi, and Mbola had assessed Astrid’s costume.

“What are you supposed to be?” Mbola had finally asked, her voice filled with no small amount of suspicion.

“What she is is highly ‘sketch,’” Young answered, giving her his highest praise in a worldview filled with two types of people: those noteworthy enough to be “sketch,” and all the rest who were just plain old “unsketchable.”

“She’s that ninja superhero chick from their comic book,” said Mimi.

“She’s a samurai. And it’s a graphic novel,” said Young.

“Whatevs, superheroes don’t wear glasses,” said Mimi, with finality.

“What about Clark Kent or Beast?” Mbola said, eager to support her wished-for future baby daddy.

“And Cyclops wears that visor thingy so he don’t burn folk up with his eyes. Ooh, ooh, and what ‘bout your girl Wonder Woman, Mimi, what about her?”

“Alter egos don’t count,” Mimi said. “When she’s Wonder Woman, she’s perfect.”

The two girls bickered as Young and Astrid swapped home evasion stories involving synchronized watches and draconian parental curfews.

At the mention of his father, Young sighed repeatedly, running charcoal-stained fingers through his crazed, anime hair, its spiky tufts defiant, jabbing the air excitedly like inky exclamation points. His Dad, senior pastor at the biggest Korean Presbyterian church in Central Jersey, bowed a head full of gelled, upstanding Kim Jong-Il hair in prayer every Sunday morning at 8 am, 10 am and 12 o’clock services. The right Reverend Yoon had serious hair and serious plans for his son to be leader of his flock someday.

Plans that did not involve Young’s blind older brother Park or having his youngest son succumb to a life of frivolous etching.

“You’re going to have to tell him about the letter sooner or later,” Astrid said. “You have to speak up for yourself someday, senpai.”

“Right back at you, kōhai.”

There were two letters actually: Young’s acceptance to a fine arts program at Pratt and Astrid’s to Princeton. Hers was in the note-book she carried everywhere, kept close to her chest like a breath or a promise. Young’s was tucked away, alongside his art supplies, in a hidey hole at school. Both were safeguarded from mothers who “accidentally” read your diary or fathers who sprinkled your “heathenish” art work with holy water.

Young had sighed once again. “Look, tell her you don’t want to go to Princeton. What’s your mother gonna do? Whip out The Photo again?”

The Photo was legendary among her friends, holding sway in their collective imaginations like lore of the One Ring or the Sorcerer’s Stone. Astrid had first seen The Photo when she was ten years old, slipping peas to their dog, Ahidjo under the dining room table. Her mother put her fork down and left the room. She returned with a photo—it was not The Photo yet—but her mother held it up to her face with all the import that it would soon come to hold. You see, Astrid had grown up listening to her classmates’ stories of how tricky parents guilted them into eating liver, Brussels sprouts, and the like with tales of all the little children starving in Africa. Except for Astrid, there was no mystery mal-nourished African child behind door number two.

That child was real.

That child was a relative.

“This is your cousin Adama,” her mother had said, pushing the photo even closer to her face, “Look at her! Do you think she can refuse food? Do you?” And Astrid had looked at the little girl standing barefoot in a blush of red dust, yet improbably clean; clad only in a trophy-shiny Super Bowl T-shirt, donation bin-wear from a team that had lost the championship. Adama stood there smiling, a mud brick hut behind her, an uncertain future ahead of her, and the photo became The Photo: her mother’s insurance for her good grades—Adama’s parents could barely afford her school fees—and good behavior—if Adama misbehaved, she was disciplined with a caning. It had worked for a longer time than Astrid was willing to own up to, even to herself.

“I can’t tell my mother anything,” Astrid said. “She’ll kill me.”

“Sure, she will.”

“No, I mean it.” Suddenly, Astrid had a vision, so vivid—Mittyesque her mind supplies. God, she wished her life was that Technicolor, or un-life, as it were. There she lay, her lifeless body prone with arms akimbo in a ghoulish foxtrot, in a photo labeled “Exhibit A.” There was Gwendolyn, her somber older sis the attorney—African parent-approved career #1—defending her mother in court as her brother Elias, the doctor—African parent-approved career #2—testified about “mental duress” and “temporary insanity.”

“If only she had gone to Princeton and become an engineer!” Her mother wailed as a jury of sympathetic peers nodded in understanding. Lawyer, doctor, engineer—the high holy trinity of professions blessed by African parents. Writing graphic novels? No. Friggin’. Way.

#

Astrid and Young “Money” Yoon’s table is at the tail end of a striv-ers’ row of indie comic labels, one-off prints, and handmade fabulist’s figurines. For a moment, Astrid is hopeful when she sees Young talking to a guy who is leafing through their dwindling maybe? stack of merchandise, but then she puts her glasses back on and realizes it’s no customer, just Abel—the skeevy owner of the comic book store at their mall.

“How big was your print run?” Astrid hears Abel ask, as she steps up to the pair, lychee bubble tea in hand.

“’Bout 1000,” Young says.

Astrid nearly spit-takes her boba at Young’s inventive salesmanship. They had really only printed 300 copies of The Seer: The Tales of Augur Brown, a blind swordswoman—Zatoichi meets Cleopatra Jones. Augur had an eerie ability to see inside evildoer’s souls and dispensed a blade-based justice, according to a personal ethos loosely derived from bushido code and the laws of the street.

“Wow, you mean business, dude. I thought this was some sorta vanity project.”

“We told you we were serious about this,” Young says.

Astrid smirks at his emphasis, she can’t help herself.

“Tell you what. I’ll display a coupla copies on my shelves and go in 50/50 on the sales price. Deal?” says Abel, head bobbing in emphasis. His graying ponytail practically wagged with excitement at the thought of profits.

“I’ve got to discuss it with my business partner.” Young looks at Astrid.

“Sure, sure. You do that,” Abel says, then turning to Astrid, says, “Nice get-up.”

Astrid looks at his retreating Hawaiian-shirted bulk, then at Young. She raises an eyebrow.

“I know, I know. He’s a chauvinist ass, who only likes his girls chesty and splayed across comic book covers. Blah, blah, you said it already. Now get over it.” He smiles.

They both knew about Abel’s collection of hentai back in his store room; his top shelf titles held for special clientele with a taste for saucer-eyed dakimakura girls, kitted out in abbreviated plaid minis with Hello Kitty backpacks, and being ravaged by slimy tentacles in every orifice.

“Whatevs,” says Astrid, turning to go. She smiles sweetly. “BTDubz, your girl Mbola says ’Hi’.”

“She’s sooo not sketch,” Young replies.

The first time Young had called Astrid “sketch,” she had kept quiet. She’d just shown him the first draft of her script for Augur Brown’s next installment. They were sitting together on a tweedy brown sofa in a tucked-by corner of the library, their legs inches apart but no actual contact ever made. Astrid found herself wiping suddenly-clammy hands and then her glasses on the hem of her flowery summer dress. Daffodil petals swept clean one lens then the other. Young was silent, poring through her work. When he looked up his eyes seemed to pinball all over her. What was he thinking?What was she thinking? She wrote stories in the margins of textbooks: tales of a father killing his infant son to end a family curse unfolded alongside tangents and quadrants in Bittinger’s Algebra and Trigonometry: Seventh Edition with enhanced study guide: a tale of two sisters on a Jack Sprat spectrum of eating disorders: one anorexic, the other obese, was in the paginated sidelines of Essential Physics by E. W. Rockswold. A niggling shame began coursing its way through her body, burrowing in deep like a chigger, down, down, down. Young finally looked her in the eye, then cast his gaze on the page, then on her again.

“Thank you,” he said simply, pulling out a vast, world-building expanse of drawing paper. He drew her. It had taken all of five minutes but when he finished it felt like the first time, in a long while, that anyone had ever seen her, the real her. Not the “you’re pretty for a dark-skinned girl” or the “damn you tall, shorty” regard that made her feel like some gawky girl Groot.

Young found her lovely. He found her, like he had set sail that day and miraculously discovered her, landing, wide-eyed and intrepid on uncharted shores.

That night she went home. Said the proper “yes, Mummys” at the dinner table and dutifully passed the egusi stew when prompted, all the while this new awareness surging inside like a secret superpower, tingling through her. She looked up sharply. Had her mother just given her a look from across the gari? She gulped the rest of her food as quietly as possible.

Later, in the dark of her room, she was glowing. A thousand Christmas lights flashing and manic, just under her skin. The sensation only just bearable. She knew how to be quiet about relieving the tension, no telltale rustling of bed sheets, no sighs—just a long pillow held tight between the soft V of her thighs, then a squeeze, a squeeze, a squeeze.

#

After way too many texts—where u at? /getting sumthin 2 eat/by auditorium/naw, by Spidey statue/huh?—Astrid finds Mimi in a clutch of adoring fans posing for photos. Mbola is ringside, holding Mimi’s Gucci purse. Astrid supposes all the attention is partly the novelty of Mimi as a “black girl Psylocke,” but most probably because her costume is basically a leotard and some strategically placed purple scarves which barely conceal her massive boobs. Mammaries, Astrid thinks. Mammaries.

Back home in Cameroon, some tribes iron girls’ breasts when they develop too fast. Wooden pestles pounded foufou and flesh alike, anything that was sharp or unyielding would do really: a grinding stone, a coconut shell, a hammer held steady-handed over hot coals. Mothers beat down their daughters’ breasts to keep them safe from come-too-quick womanhood, from the lingering gazes of that older Uncle, that school master, that strapping boy in the classroom’s corner desk at their secondary school. Her mother was born of this tradition. Astrid sometimes caught her mother eyeing her long, wayward limbs in exasperation, as if her growth spurt was somehow a calculated rebellion. Astrid tries to be good, she does, but the harder she tries the harder her mother becomes, still. Her sister Gwendolyn had tried to explain it once, stuff about Astrid being the “last cocoa,” the late-life child their flagging mother tried doubly hard to keep in line yada, yada, yada. It was all so exhausting—her mother’s worries, her nameless fears—but Astrid supposed this was why her mother had lied about The Photo.

A week ago, Astrid had learned the truth, surrounded by dark Twilight poster boys vamping at her from the walls of Mimi’s bedroom. She was checking her Facebook page: scrolling past four pokes, two event invites, and then onto three friend requests. Two were easily dismissed but the third was from some girl she vaguely felt she should know. Someone from summer camp, a Sugar Pine alum maybe? No, the girl listed her hometown as Bamenda, Cameroon. She almost asked her girls if they knew her, but they were busy: Mimi, supposedly studying but in actual truth, instant messaging with a Parisian bodybuilder on Snapchat and a Filipino Tinderoni in BK; Mbola, checking out YouTube tutorials, how-to vids by Ms. D. Vine on the best way to install your own lace front weave. She looked at the girl’s warm, glossy-lipped smile again and stopped cold. It was Adama. As in her cousin, Adama. Adama with 579 friends. Astrid had 32. Adama in dozens of duck-faced selfies and ussies. Astrid had a grainy, class photo as her profile pic. Wearing bifocals, no less. There was Adama with a braided faux-hawk, with kinky twists, in an Escalade, on a merry-go-round, with a cleft-chinned guy tagged as Okono Tambe and a barrel-chested footballer, a Mark Konwifo. What the–?

Astrid jumped up, stumbled to the bathroom, and promptly threw up.

How lame is my life? She thought, then dry heaved once more. Twice more. What life?

Two days later she got her acceptance letter to Princeton, its words standing dark and ominous against the creamy paper. It was official. The reality of that almost made her throw up again. She felt ridiculous for dreaming beyond the picture-perfect life her family wanted for her: nice cars, nice houses, nice husbands, nice jobs. All so tidy. So prefab. Sometimes she went to the mall to get messy, to fuck things up. To pocket pens behind the cashier’s back and fill that well inside herself. Why? Why did she have to make such a mess of things and want more?

“Ouch. What the–?”

Someone just stepped on Astrid’s big toe. Post-photo-op, there is some slight jostling and jockeying for position among the tight band of young men—some spandexed, some not, some with eager lenses jutting, some with limp camera straps dangling and tangling as they pressed in close to her friend. Astrid moves back a bit and her sheathed katana pokes a guy in the belly.

“Sorry,” she mumbles.

“No worries,” he says, looking her over as he rubs his deflated paunch. “Who are you supposed to be?”

“I’m still trying to figure that one out,” Astrid replies.

#

Astrid stares down at the NYC subway bench with its ritual scar-ifications, its palimpsest of celebrity memorials: Tupac 4 Life, R.I.P. Biggie, Forever Whitney. On their trek back to Jersey, Mbola and Astrid sit together silently for a number of reasons.

First, their mouths are full. Astrid is chewing wasabi nuts; Mbola is sucking on sunflower seeds, spitting their recently desalinated husks in a long trail that makes Astrid think of children lost in fairytale woodlands.

Second, they are exhausted. The rest of the afternoon had surged forward in a blur: an advance screening of a new Whedonverse TV show; Mimi’s “honorable mention” in a cosplay contest; a pretty informative panel on how to survive the impending zombie apocalypse. While the “panelists”—three guys in fatigues toting Day-Glo orange rifles—handed out copies of an actual Center for Disease Control zombie-preparedness guide, Mimi and Mbola argued survival scenarios, should an outbreak happen in Africa. Mimi figured high body counts: They can’t even cure Ebola, let alone some zombie virus. Mbola was a tad more optimistic: Stop playing. They would ether them zombie mofos. Them motherland Africans stay packing machetes. Astrid tuned them out and took detailed notes, research for her lemony Richonne one shots, on the instruction drills for how to kill or successfully elude the walking dead. Differentiating, of course, between Romero’s slow, lurching Dawn of the Dead revenants and the fast-moving undead “zoombies” of 28 Days and its ilk. Kill shots to the head were deemed universally appropriate.

Third, and most importantly, Astrid and Mbola are silent because they are alone. Mimi, their buffer, had decamped to a cousin’s house in the Bronx, leaving them in one of those awkward moments when their simmering dislike—usually confined to the occasional whitehead flare-up—now took on a life its own, gained sentience, planned world domination.

Mbola spit out another sunflower seed, breaking the silence, saying, “I read your stuff today. It’s mad dark.”

“Yeah, that’s Young’s style,” says Astrid. Young was crazy for chiaroscuro—all inky blacks, bone-whites with the occasional splash of red in a flagrant homage to his idol, Frank Miller. Her story lines fit the tone.

“You know just what his style is, don’t chu?” Mbola says. “The way you be all up on him, all the time.”

Astrid knows that Mbola is decidedly not Young’s style. He had dismissed the idea of dating her in less than a minute.

Mbola? I’d rather date a Japanese body pillow—better personality.

She’s not all that bad.

She’s crazy, and loud, and –

Whatevs, date the pillow chick. I’m sure you and Keiko-tan will have a nice life together.

Damn straight. Once you go moe you never go back.

Mmmhmm. Better not honeymoon in Paris though.

Astrid had dropped an imaginary mic as she said this, then threw her hands in the air for that burn to end all burns. Shinnichis that they were, that Sunday night’s viewing pleasure had been a docu-mentary on the frequent mental breakdowns of Japanese tourists in the land of croissants and vin rouge.

Alright, alright. I gotta give it up for a PBS snap. Young said, laughing.

“Astrid! Is you listening? You don’t got nothing to say? You too good to talk to me?” Rat-a-tat questions from Mbola, who was working herself into a state, firing up.

“No, I just–”

“Yes, you. You always looking at people and writin’. What you got in that pad about me? You know you ain’t better than nobody. You ain’t no hero.”

“What are you talking about?”

“Tahlmbout you, bitch. You s’posed to be that blind ninja chick, Blue Ivy, Augur Blue–”

“Brown.”

“Blue-black, doodoo brown, whateva . . . You ain’t her, you weak,” says Mbola, poking a long acrylic talon at Astrid’s face. “She can’t see but at least she can open her damn mouth to talk. More than your ass can do.”

“Get your finger out my face,” Astrid claps back, refusing to step away, to cower, but then she falls silent. She always falls. The platform is hollow with her silence till the homeless man slumped over three benches away lets out a random fart. Till Astrid hears the muffled rumble of a train approaching on the opposite track. No more, no more, no more, no more, she thinks, feeling a pounding in her blood as the train, and Mbola draw nearer. No more, no more, no more, no more!

Astrid flashes to a vivid scene, another vision. Her katana slashes at air and sinew and bone. Blood blossoms from jagged platform cracks like vengeful roses. All that is left of Mbola, and her scorn, lies ruined at her feet.

“Hey! I’m talking to you!” Mbola’s strident voice zaps Augur/Astrid back to reality.

“Yeah, get all quiet again, smart-girl,” Mbola continues. “You so smart, why come you got to sneak out your house? Why you stay lying to your Momz all the time?”

Mbola pushes her then. And for the first time in her life, Astrid pushes back.

She slaps, she jabs, she dodges Mbola’s left hook. In their tussle, Mbola grabs her knapsack. Pulls away, panting and triumphant, holding it over the tracks.

“I’ll drop it, bee-yatch,” Mbola snarls through a bloodied, already swelling lip.

“Just try it,” Astrid says, slowly unsheathing her katana. It’s a dull replica really, but she knows if she puts enough force behind a blow, it will hurt like a motherfucker. Her mind fills with chiaroscuro, a darkness of slashing things: Mbola, Abel, her mother, and finally The Photo—nearly bowling her over, nauseous with a need to hurt something. But then suddenly there is a lightness. She feels freed, and is filled with an awareness of her life beyond this moment, a future that is hers to choose, so she hopes. And there’s that tingling again, the itching, sticky glow of it under her skin. She knows the truth of it now.

Mojo, Astrid thinks. Mojo.

She lifts her chin high, lowering her sword to her side as she walks towards Mbola.

“Just try me,” she says.

Art by Maggie Nowinski.

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#33999′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

[av_one_half first]

[/av_one_half]

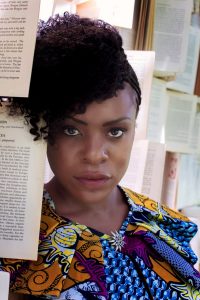

Nana Nkweti is a Cameroonian-American writer and graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. She was the Fall 2017 Phillip Roth Writer-in-Residence at the Stadler Center for Poetry and has been awarded fellowships from MacDowell, Vermont Studio Center, Ucross, Byrdcliffe, Kimbilio, Hub City Writers, Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and Clarion West Writers Workshop. Nana’s writing has been published and is forthcoming in journals and magazines such as Brittle Paper, New Orleans Review, Masters Review, and The Baffler, amongst others.

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#33999′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]bridge media | Nike Shoes