[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#1f4378′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

He’s been sober now for decades, but in the early days of his teaching career, when I was his student, he was deep into the destructive work of booze. It was a time when the ampersand was intentional & historical, Beat shorthand for every slow, tired “and” anchored to old times. It was 1974, Fort Collins, Colorado, my first year of grad school & lots of amped-up ampersands. Wild West creative writing program, not yet legit, not MFA’ed. Refuge for renegades & green writers. I was green as could be.

Back east in the Green Mountains (an undergrad at UVM), I’d made a very small dent in the literary canon –white men, many stodgy, some thrilling, all of them dead. I’d read nothing modern, nothing contemporary. Yet, I wanted to be a writer. I’d jumped ship a few times – pre-med, to psych, to eastern philosophy, to literature & one creative writing course. That was all. I loved Shakespeare, Keats, & Yeats. That was all. And on that shaky basis, I was admitted to CSU, provisionally: within the year, I must demonstrate I could write or be out on my ear.

Bill Tremblay was my teacher, my mentor. Wild Bill. Like me, he’d grown up in Massachusetts mill towns. Like me, he loved jazz. That’s where the resemblances ended. Bill was second generation Beat, influenced by Ginsberg & Kerouac. In 1974, he ran workshops in the bars as often as in the classroom. Fledgling writer that I was, Bill took me under wing. Writers drank, he said. I drank. I drank a lot. Bill read Tarot fortunes without the cards. Bill juggled seven conversations in the air without dropping one. I tried to be a minor fortune teller & hipster & failed. Bill was jazz & drugs & booze & all night binges in the bars & post-bar 12-packs in his car parked somewhere on the eastern Colorado plains, watching chain lightning run up & down the sky or watching a red sunrise bleed in the east. I watched a lot of lightning with him, watched a lot of sunrises, eyes bloodshot. I drank hard, well into my second year, until one night, I wanted to stop.

A claque of grad poets gathered around bottles of mescal, shoved at us by Bill. Drink, drink up! We swigged & swigged. At some dizzying point, I rejected the bottle. He shoved it back at my face – Drink, drink up! I turned away & then he was on me, wrestling me to the concrete floor. My mind blinked: I was wrestling with…my professor…over a bottle of mescal, wrestling with an angel & demon wrapped in one body, mentor/tormentor…But I’ve gotten ahead of myself…

In my first, green year, Bill pushed poems on me: You absolutely MUST read this… some new blast by Ginsberg or Bly, Lowell or Sexton. Bill pushed me to write poems I didn’t know I could. His voice charmed. He could read the phonebook & make it sound like a list-poem. When he ordered a burger or a beer, it sung like a haiku or jazz lyric. He did performance art before performance art. I couldn’t tell if his poems were good, blinded by his charisma.

Bill had given me two semesters to turn my game around, so I started to write like Bill, long associative phrases strung together, slightly surreal, full of fire & keening & dissociative moments that either stung like a tarantula or petered out like sawdust on a barroom floor the morning after. He gave me some Confessional advice: read Lowell’s Life Studies. Write about your family. I wanted to write love poems, nature poems. Fuck love, fuck nature, Bill said. Write about your family. & make it hurt.

I wrote six short poems & hit a wall. Somehow, I moved the wall & wrote a dozen long poems I called “The Father Poems.” They were about my father. & not about my father. The more I revised them, the less they were about him. The more I wrote like Bill, the more they sounded like Bill. My father did wild, preposterous things: danced in jazz bars till dawn, blanked out the names of his kids & wife, blacked out, woke in strange beds or on the skid, wrestled Vietnam vets out of their PTSDs, went blind as Homer, recited by heart like the Homeridae & went 100 mph round & round the brain circuitry. Soon it was obvious who “The Father Poems” were about.

Each week I took new drafts to his office. Bill loved them like a son. He praised their style, wildness, fresh riffs on this sonuvabitch of a father. What a monster, said Bill. What a horrible, horrible man! he moaned. Now I understand you, he said. What you’ve suffered. I winced, I cringed. How could I tell him the horrible truth. Mentor & Tormentor. Mon frere, mon semblable! Had I read Baudelaire, I’d have had the words.

Eventually, Bill sent “The Father Poems” to a state-wide, grad school writing contest, Richard Hugo the final judge. 1st, 2nd, & 3rd place winners were not me. In that most abominable of categories, Honorable Mention, appeared my name. At the awards ceremony, Hugo spoke briefly about the winning poems, then turned his attention to “The Father Poems.” He called them heartfelt, full of wild energy, drunken disintegration, desperate longing for integration & acceptance, desire to be healed by a father’s blessed hand. I was very glad the poems were that good, proud for myself, & prouder still for my secret mentor & tormentor, Bill Tremblay.

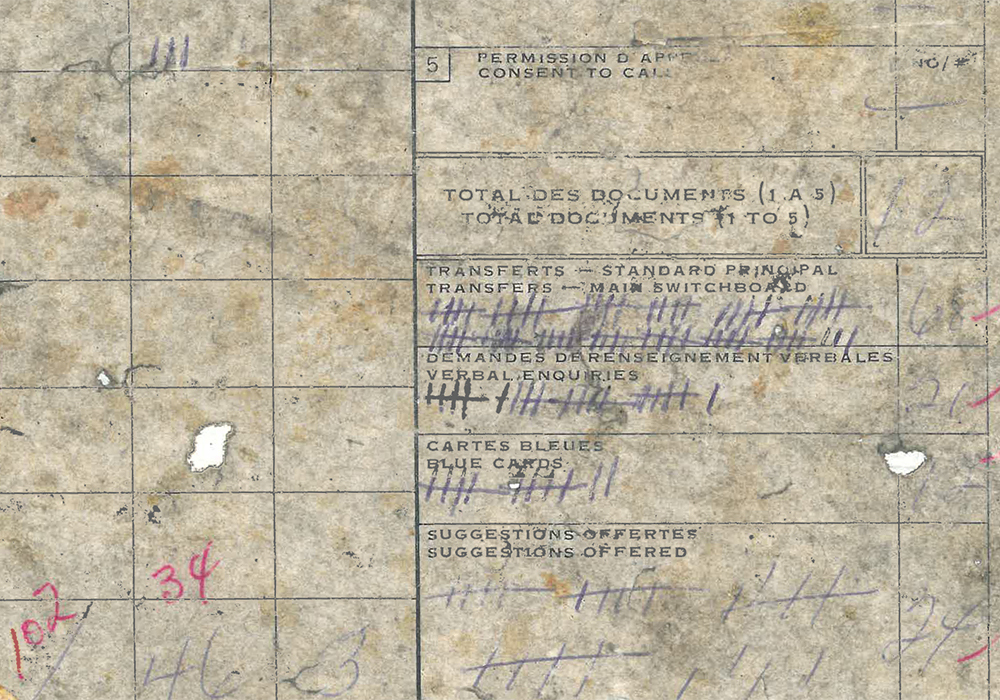

Art by Matt Monk

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#1f4378′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

[av_one_half first]

[/av_one_half]

Neil Shepard is an American poet, essayist, professor of creative writing, and literary magazine editor. He is a recipient of the 1992 Mid-List Press First Series Award for Poetry, as well as a recipient of a fellowship from the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts and the MacDowell Colony.

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#1f4378′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]Running sport media | Women’s Nike Air Force 1 Shadow trainers – Latest Releases , Ietp