At the Crossroads of Woman and Mother

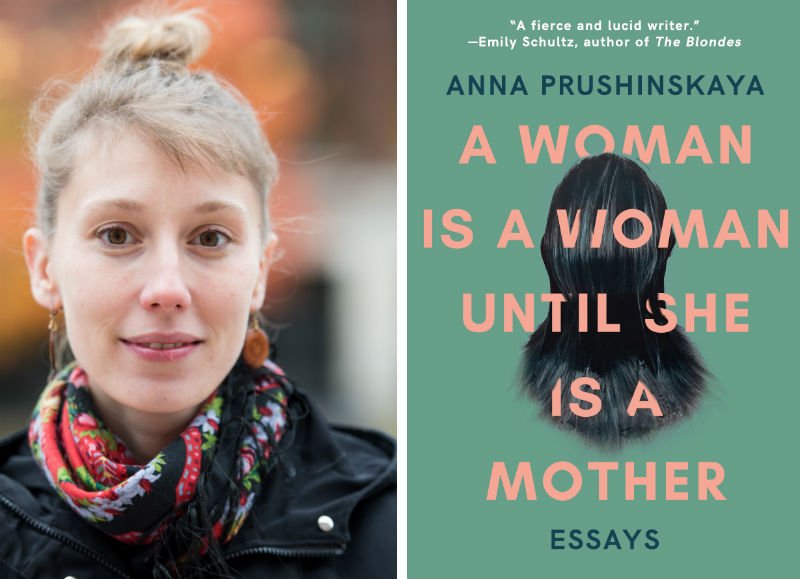

A Review of A Woman is a Woman Until She is a Mother by Anna Prushinskaya

How are women’s stories told? Who hears these stories? How do the terms ‘mother’ and ‘woman’ relate and differentiate? Can they coexist? These are some of the questions Anna Prushinskaya tackles with lyrical honesty in A Woman is a Woman Until She is a Mother, her debut essay collection. Her book unpacks the complexities of motherhood itself, as well as the transitions of “woman” to “woman with child” and from “mother-to-be” to “mother.” Through a mixture of her own meditations and examples given by respected female writers and thinkers, Prushinskaya illustrates that “mothers” are women as diverse, as complicated, as unique, as flawed as any other group of humans, and deserve to be recognized for their commitment to take on the demands of maternal work on top of the demanding struggle of being a woman in today’s society.

Prushinskaya structures her book along a chronological timeline. Bookended with the inscriptions “Does it help to know this was written while I was pregnant?” and “Does it help to know that this was written after I became a mother?”, the essays document Prushinskaya’s growth into her own identity as a mother. We are privy to witness the fluctuation in emotions and confidence as that identity changes.

Throughout the eleven essays, she artfully weaves together a wide-range of seemingly disparate topics, including technology and online maternal support communities, home births versus hospital births (Prushinskaya herself works as a doula now), the wonder of forests, and her own family’s heritage and memories of the former Soviet Union.

The book begins, fittingly enough, with the grandest mother of them all: Mother Earth. “Love Letter to Woody Plants” at first makes us wonder if we’ve picked up the wrong book. We weren’t expecting a naturalist’s diary. Speaking about types of maple trees, she writes: “They have a thorny, suckering habit. They are part of one another.” She observes that “the forest changes…[it] is strange and lovely, a place to touch and explore…I am not particularly spiritual, but I quiet…My instinct is to not to trust [the forest].” Even as she speaks about nature and its changeable ways, a subtext of self-doubt and the physical metamorphosis of life forms introduces us into the major themes of the collection. We can’t help but regress into childlike wonder amongst the backdrop of such natural splendor.

Does it help to know that I am a woman and a writer? Does it help to know that I read this book and am not a mother?

“It is a strange thing to know someone based only on what they feel like from the inside,” Prushinskaya says in the collection’s titular essay. Speaking from the precipice of becoming a mother as a woman 37 weeks pregnant, her anxiety and doubt create tension as we wait, too, for her water to break. She balances the anticipation with a delightfully dark sense of humor: “I took a shower. The shower was hot, and I worried about whether I was scalding the baby…I felt a pop and a gush, the sort of thing that happens in the movies and is actually very uncommon. I spent my pregnancy pointing out instances of such unrealistic portrayals.” At the climactic moment of her baby’s birth, she turns her experience into something beautiful and metaphorical, something that only a master poet could put into words: “Motherhood is an encounter, a shadow in mirrors, a beast laying low in the grass in the field.”

The personal essays are lyrical in nature, which comes from Prushinskaya’s early roots in poetry. She has an intimate and down-to-earth voice, yet not so intimate as to confide everything to us. Her language is careful and controlled. There are moments in the essays where Prushinskaya hints to hardships in her past, such as an abusive relationship or a possible addiction. With no further elaborations, her narrative stays focused on the topic of motherhood; thus communicating that the hardships she’s overcome are part of who she is today, but are only sideline spectators to the story at hand.

Prushinskaya’s last essay, “One Mother’s Answers,” takes the hyper-experimental form of a one-sided abstracted conversation, in which we only hear the mother’s answers. We must fill in the blanks with our own questions. The author here begs us to remember that while some questions are universal, each person’s answer is distinct. The memory, the voice, the cadence, the preoccupations—all unique.

Throughout her essays, Prushinskaya both pushes back on the constructs pinned upon mothers (be selfless, be perfect, be gentle) while actively seeking to embrace the image of doing motherhood right. This ability to see her identity as a “both/and” instead of an “either/or” makes this collection highly evocative and admirably honest.

Does it help to know that I would like a family one day? That I want to continue to work and write. Does it help to know that I want to love a baby from my own body? That I’m scared, excited, curious, clueless.

Prushinskaya’s collection gives me permission, as a woman writer, to have all these emotions simultaneously.

It is true that this collection is firstly concerned with telling a woman’s story. In fact, the only men who appear (briefly) in the book are Prushinskaya’s husband, the “EMS guy,” and the author’s Russian grandfather. But Prushinskaya reminds us that “we are all a history of someone else’s limbs.” We are all born from mothers, no matter our gender. A mother is a mother even when you grow up. A mother’s story may even be a prehistory of you.

A Woman is a Woman Until She is a Mother is undoubtedly an important contribution to the world of women’s stories. From the book’s beginning to its end, Prushinskaya strives to showcase one writer’s definition of herself as a “woman.” Being a mother, for her, was a choice; a voluntary path she understands is not available to all women. She shows that there is no right way of being a mother, nor of being a woman, and ‘the right way’ to be that person can change daily. Perhaps there is no ‘right way.’