[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#372a55′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

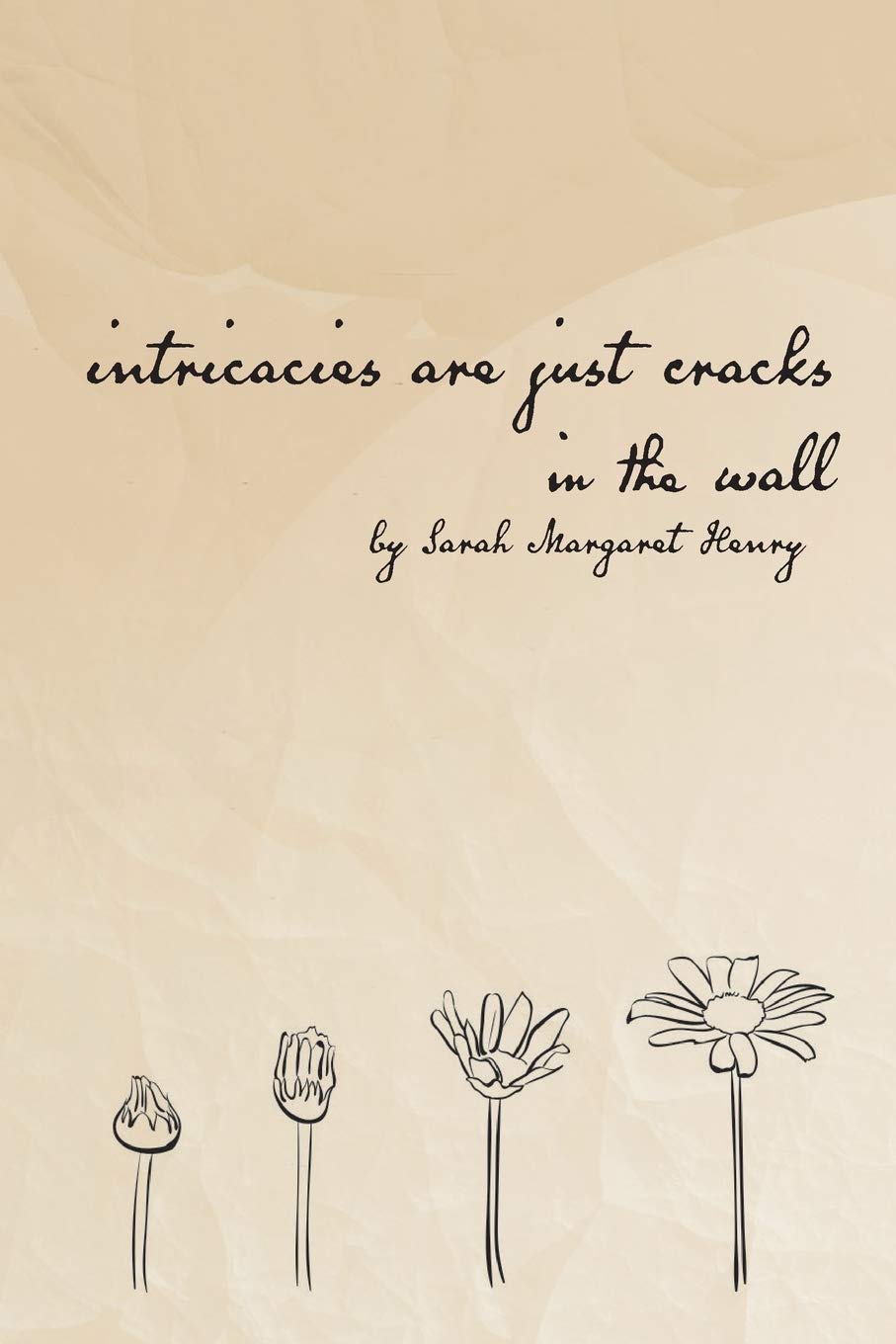

intricacies are just cracks in the wall

By Sarah Margaret Henry

122 pages. Still Poetry Photography. $15.00 (paper).

intricacies are just cracks in the wall, a debut collection of poems and lyrical prose by Sarah M. Henry, came to my attention by word of mouth and via Goodreads. There was a small buzz of excitement among my college friends regarding this book. I noticed that a few of them were marking the book as ‘want to read’ on Goodreads. A few weeks later they switched their status to ‘read’ and left compelling reasons for why I should read this collection. I was told, “it’s not like any poems you’ve read before.”

While poetry is not usually my genre of choice, I was willing to give intricacies a shot and I’m glad I did. This book isn’t comprised of just hidden meanings and figurative language like a lot of the poems I have been exposed to in school. Henry’s intricacies are just cracks in the wall is different than your run-of-the-mill poetry collection because it tells a story that is typically silenced.

intricacies are just cracks in the wall is an example of narrative poetry. Narrative poems tell stories or a single story through a collection of poems. This device is not new, but it was new to me. The only other narrative poems I have read are ancient epics The Odyssey and The Iliad, but this story was much different than those. While the epics are made up of formal poetry and special syllabic formations (iambic pentameter and dactylic hexameter), intricacies are just cracks in the wall slips between informal and formal poetry.

intricacies follows Cassidy (“Cass-i-dy, say it loud, say it proud”) through three relationships—a relationship with Jack, Oliver, and ultimately herself. Told in the first-person point of view, these poems are broken into three parts: “gradual crucifixion,” “perforated internment,” and “self germination.” These three parts tell the story of a girl who ends up in an emotionally-abusive relationship, eventually breaks free and finds herself a new, healthy love interest, and also learns to love herself again.

Henry quickly displays Cassidy as a proud young adult eager to take on the world “that is [hers] for the taking.” She unabashedly takes up space, as her mom told her to do, and she wonders if there is enough of her to fill the new apartment that “on paper / [she] knows is [hers].” She gives herself three days to get settled in before starting her first day as an editorial assistant.

After Cassidy, the audience is introduced to Jack, who seems amiable and gregarious upon first encounter. Jack helps Cassidy move in. Before leaving for the day, he scribbles a note on a business card “Hey Socrates, / Since you’re so interested in commiserating, Tuesday, 7:00, Pints Bar & Grille?” and leaves it in Cassidy’s annotated copy of The Critique of Judgement by Immanuel Kant. The Critique of Judgement is about aesthetics and beauty. Henry has Jack very artfully use Kant to ask Cassidy out. By using Kant, it is as though he is latently telling Cassidy that she too is beautiful.

Cassidy and Jack meet up first at Pints and then again at the Midtown Scholar (a bookstore in Harrisburg). At the Midtown Scholar is where readers first learn Jack is a little bit of a chaotic character as he “tears loose the copyright page” from one of the books. He proceeds to write a poem on the page and hands it to Cassidy. Through this, readers see he doesn’t mind destruction even if it’s for the sake of beauty.

The relationship between Cassidy and Jack continues to develop and Henry places subtle hints that more red flags are going up. Jack begins to call her Cassie “Before [she] can say / It’s Cassi-”. While that in itself isn’t wholly problematic, it shows he doesn’t listen to Cassidy who is proud of her three-syllable name. Henry also brings in the importance of consent. She writes that Jack “barely gives [Cassidy] enough breath / To collect a no from [her] lungs” when, on date five, Jack tries to get more intimate. Despite these red flags, when Jack’s landlord’s building is foreclosed, the two move in together because isn’t that what people do who are in a happy, healthy relationship?

Henry mostly maneuvers between free-verse poems and lyrical prose with a crown of “Panicked!” sonnets thrown in towards the middle of the collection. While some pieces are longer with more complicated subject matters (58) and others are bite-sized and easily digestible (61), each selection allows the reader to get more inside of Cassidy’s brain and her way of seeing and interpreting the world around her.

Sonnets are usually associated with love stories and happy endings. Henry artfully places her sonnets 65 pages into the collection. However, the pages do not crescendo into a traditional love sonnet for Jack. Cassidy has realized by this point that though her apartment “looks like a mouth / Filled with missing teeth / [she knows] they were rotting cavities” and “Everything missing is his.”

Instead of being a love sonnet for someone else, Henry’s “Panicked!” crown of sonnets conveys a message of self-rebuilding and reconstruction. It is also showing a literal restructuring as Cassidy begins to take medication and starts to reorder her life. From the first sonnet, Henry focuses on giving Cassidy a “meaning to existence,” an existence for herself, without Jack. While it is hard at first (“Something simple as a broken teacup / Could cut so deep and fully overcrowd / My mind”), Cassidy begins to reimagine what life can be like (“A shadow slowly growing some color, / Metastasizing into a body”).

intricacies are just cracks in the wall is an important read due to its structure and its content. While people may be familiar with narrative poetry due to ancient epics, readers can experience a modern-day narrative poetry experience through this collection. People who are usually put off by the metaphorical and figurative language of poetry should give intricacies a chance because it puts storytelling in a new light.

We don’t typically get to hear what goes on during an abusive relationship while it is happening. Henry uses the concepts of destruction and beauty throughout intricacies. She shows a relationship, fragments it, and then readers get to watch while Cassidy picks up the pieces and redefines what love means.

All this being said, readers should be cautious when approaching Henry’s collection. It digs into an unhealthy, emotionally-abusive relationship that may be triggering or off-putting for some people. By writing this book, Henry is helping to erase the stigma that surrounds abuse and abusive relationships. This book is an important read not just because it is able to tell a story through poetry but because the story she is telling is one that often isn’t voiced.

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#372a55‘ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

[av_one_half first]

[av_one_half]Noelle Thomas is a creative nonfiction writer from the greater Philadelphia area. She enjoys space (both outer and personal) & drinking tea. When not in school, she can most likely be found at her gymnastics gym or at the zoo.[/av_one_half]

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#372a55‘ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]