[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#1f4378′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

Here is what I like to think happens when we die: first, we float. Alone in boundless blackness, we are conscious only of absence. Then, all around us, faint pinpoints of light brighten slowly, imperceptibly, so we don’t notice until we’re surrounded. A luminous map of stars pulses into focus, accompanied by a swelling of strings from an invisible orchestra. We can make out far-off planets and hula hoops of debris around them. Purplish clouds of galactic dust yawn in the distance. Then, all at once, we’re flying, everything a blur of blue and orange and black, and the brass section kicks in with spirit, crescendoes, louder, more trumpet there, and we are hurtling through space faster and faster, and then, then, just when our teeth begin to grind with anxiety, an Earth-like oversized marble of a planet grows huge in front of us, and with a jolt we stop.

Here, orbiting the planet, is our gleaming, blinking, permanent destination: a space ship of some sort, a giant dinner plate attached to a sled.

What we do not understand is then made clear by a reassuring voice, booming out over synthesized ambient chords:

Space, it says, Britishly. The final frontier.

And with that, we materialize bodily within the salmon-carpeted corridors of the Starship Enterprise, where we will live out eternity via a series of fifty-minute interplanetary parables with the rest of the crew. There will be apparent risks, but we will take them all, we will follow Captain Jean-Luc Picard’s bobbing pate into any dark corner of the universe. We will be post-race, post-religion, post-war, post-disease, post-death itself: we will be the future.

This is my father’s fault.

~

Twenty years after Star Trek: The Next Generation first aired on TV, I have rented all of seasons two and four, curled myself into the arm of a couch with a glass of bourbon and barely moved for three days. Because. Well, because seasons one and three were already checked out. Or because it’s the edge of a sharp winter. Because something needs sopping up.

But mostly it’s because there is Captain Picard’s swagger. He swaggers elegantly. Long leggedly. Ring of distinguished gray fuzz arcing over patrician ears, gloved in a redblack Spandex uniform, eyebrows expressive as caterpillars. And there. Something bubbling up, over. There a choked desire to be shown something future and past at once. And Jean-Luc Picard, all aged but not yet elderly, all hero space pioneer, there, the way he swaggers across my TV screen now is the same way he once swaggered across the TV screen in my parents’ bedroom every Saturday night after dinner.

It’s not time travel, but it’s close enough.

My father liked Picard, liked Star Trek, maybe for the gravitational directive to seek out new life and new civilizations. Maybe something softer. On Saturday nights he draped himself over the long reach of his recliner, remote at the ready. He was smitten with the Enterprise’s redheaded medical officer, to my mother’s irritation, but she popped popcorn and stretched out on the bed anyway, rolling her eyes at Dr. Crusher and trying to find wrinkles. My sister and I puzzle-pieced in front of and behind our mother and our father tapped his chin with his wedding ring during commercials.

In hindsight, this ritual was singular: a lifting of my father’s unspoken ban on mindless pop-culture in the house. But the year Star Trek: The Next Generation premiered, my father was diagnosed with colon cancer. The future, then, was maybe in short supply.

˜

In episode #202: Where Silence Has Lease, the Enterprise encounters a hole in space. On the giant view screen that spans the front of the bridge, it appears as a jagged maw against the white-dotted expanse of the rest of the sky. Dewy-faced Ensign Crusher, teenaged son of my father’s crush, reports adorably that there is no matter, no energy, no anything in the hole.

This is interesting enough to raise Picard and dashing First Officer Riker from their futuristic La-Z-Boys. Magnify. Magnify further.

The view screen shows nothing at all.

Riker raises a boyish eyebrow, strokes his lady-killing goatee.

It’s like staring into infinity, he says, musing on about a course in Ancient History he once took at Starfleet Academy, where he learned that men once believed the sun revolved around the earth and that a ship sailed too far out into the ocean would fall off the edge of the world. The Captain says, Beyond this place, there be dragons.

But then, disaster. Suddenly, the Enterprise is no longer in normal space. The Nothing has engulfed them. Their fancy instruments are useless here, their warp engines unable to move them. Blackness in every direction. The soundtrack twists itself into a minor key and we cut to commercial.

~

At the word cancer, my father’s building projects—he was always putting up extra walls to create rooms within rooms—shuddered to a stop. Dust settled and nails rolled into the cracks of the baseboards and for weeks, our house was full of frames without drywall. These mute skeletons gave us the power to walk through walls.

There was a surgery and the doctors said they got it all, and when asked to remember now my mother insists that life went on as usual almost immediately. My own record is incomplete: in pictures from the time, my sister and I produce coy smiles from under pigtails and are shod in white knee socks and mary janes.

My mother says, That first time it was over so quick.

She says, We pretty much forgot about it.

There was no such thing as history then, only possibility. And the surgeons couldn’t yet know what they didn’t then see. But I don’t know if forgot is the right word, at least not for him.

Less than three months after his cancer was removed, my father piled our little blue Ford Escort with pillows and storybooks, strapped a pile of suitcases to the luggage rack, and set a course for California, two thousand miles from our skeleton house.

The mission: just to go. He had earned the future and the right to show it to us.

~

On the bridge of the Enterprise, raven-haired Counselor Troi, who is the only member of the crew required to wear a V-necked uniform and a hint of cleavage, and whose sole job is sensing things, looks into the Nothing and reports usefully that she senses a vast intelligence.

All at once a face—or something like it—appears on the view screen. It’s just a smudge of eyes, a nose, and a mouth. Vaguely humanoid. Green. The crew gasps. Ever-alert security chief Worf, his Klingon forehead like a factory accident, leaps up, phaser at the ready, though he must know that firing at the screen would be a mistake.

The camera pulls back to include the entire beeping, blinking bridge and—oh dear— Little Ensign Crusher is no longer at his station; he has been replaced by an unfamiliar actor with a minimal speaking part. This can’t be good.

The face speaks in an echoing bass: Why are you so alarmed when I’ve gone to such trouble to look just like you? Its name, it says, is Nagilum.

Sensors show nothing there at all.

~

Somewhere near Muskogee, Oklahoma, in a wash of thin summer light, my father piloted the Escort into the lot outside a Days Inn. My sister and I tumbled cranky from the back, kneaded our sweaty hamstrings. A full day of whining and poking each other across the invisible line down the middle of the bench seat had left us hoarse and cramped but at least we were finally there yet.

Smell that country air, kids, my father ordered.

It smells, we replied, like cows. Does our room have a TV?

We tripped up the cement stairs to our room. The door swung outward, pressing us against the balcony railing, and once inside we were greeted by a large brown stain on the carpet and a heavy, sour stink in the air. A choking noise escaped our mother, and she set to work stripping the filthy coverlets from the queen beds. My sister elbowed me and whispered that the stain was probably a bloodstain and that it smelled funny because the hotel people had just removed a rotting corpse from the floor.

The murderers will probably come back tonight, she said.

The TV only had two channels.

I started to cry.

When my father, laden with suitcases, filled the doorway and surveyed, his ecstatic road-warrior grin flickered but reset. He strode over the stain, dropped the luggage on one bed and rubbed his palms together. Cozy! Who wants to check out the pool?

He wrapped my snotty hand in his, and when the pool turned out to be a muddy hole choked with leaves and bugs, smellier even than our room, my father hefted me onto his shoulders and we stood two tall at the edge of the parking lot, watching for a moment as a pair of crows looped lazily over a nearby field in the dying pink of day.

~

My mother says now, We went because it was out there.

She says, He wanted to show you girls the world, because he could.

~

The Enterprise is under a cosmic microscope. Nagilum’s big green face floats across the view screen, examining the crew on the bridge, noting differences in gender and species. It demands a demonstration of human reproduction. The crew demurs.

Counselor Troi helpfully senses curiosity.

Nagilum says, Your life form surprises me. Is it true that you have only a limited existence? You exist—and then you cease to exist. Your minds call it “death.”

Nagilum’s eyes narrow and at once, at the front of the bridge, a white light flashes and we hear a cry of pain from poor doomed Ensign Minimal Speaking Part. The camera pans down to where he’s fallen. His eyes bulge and he writhes on the floor for a few seconds, claw-handed. Dies. Illustrates the point.

Nagilum informs the crew that it wants to understand this death, and that its experiments will probably require about a third of their lives. At this, Picard stands up even straighter and more broad-shoulderedly than usual.

No! he says. We will fight you, he says. He turns off the view screen and calls a staff meeting, ushering in another commercial break. We cut to an exterior shot and the Enterprise hangs like a wind chime in the void.

Picard’s voiceover is strained:

How do you fight something that both is and isn’t there?

~

Somewhere in Arizona, the highway a wet pelt in front of us, we shuttled past a man ambling down the rumble strips. He stooped under a canvas sack and pointed his thumb at our car. As soon as she saw him my mother punched the lock on her door.

I crawled over my sister to gawk out her window at the receding hitchhiker, and she immediately kneed me in the stomach for violating our zoning agreement. I yelped and clawed the back of her arm. She gave a hard yank to my pigtail. I chomped down on her hand. She howled and pushed me back to my side of the car by my face. I aimed a kick at her shin but missed, she began summoning a monster loogie, I pinched her thigh. She growled through a mouthful of phlegm and reared back—

I think I was winning, but before my mother could twist from the passenger seat to bark back at us, before my father could drag his left elbow from its sunburned perch on the windowsill and threaten to turn this car around, so help him, there came a metallic POP! from the rear of the Escort. A flat tire. We limped to a stop on the side of the road, my mother clutching the door handle, my sister and I surprised into a truce.

Silent yellow desert all around us. We hadn’t seen another car in an hour. Grumbling, my father got out and loped back to examine the injured tire, leaving us females to marinate as the temperature inside the car mounted. My sister and I craned to watch him out the back windshield, listening gleefully to the faint stream of profanity drifting in through the open windows.

As our father squatted on the frying-pan asphalt, we saw a speck on the horizon.

The hitchhiker.

Gaining on us, steadily. We watched his figure grow for a while, until I, in a flash of inspired generosity, said, Hey, how come we don’t give that guy a ride? causing my mother to swivel back violently, eyeball the situation, and emit a strangled urp.

Windows up! Lock your doors!

She poked her head out her own window and told my father he had better hurry up, please, to which he replied that he wasn’t working on his tan, thanks.

My sister leaned over to me and whispered, We can’t pick that guy up, dummy. Didn’t you see what he’s got in his bag? A big axe. And a chainsaw. And as soon as he gets to our car he’s going to chop us all into little pieces. Even Dad. He’ll probably start with Dad. And he’ll probably kill you next because you’re the most annoying.

I started to cry.

My mother sat facing forward, wringing her hands and muttering, apparently as convinced as I was that the hitchhiker meant to slaughter us in our seats. Her watch ticked. She whined my father’s name out the window.

We could almost make out the hitchhiker’s face now, and I didn’t think I saw an axe, but couldn’t be sure. My mother jittered. He came closer.

Then suddenly, a miracle: out of the shimmer of the desert, a state trooper pulled up behind us, emerging from his car with a visible gun on his wide brown hip. My mother sucked in a breath and released her hands. The trooper swaggered over to my father and stood there in his mirrored sunglasses, watching my father grunt away at the spare tire. The trooper made conversation about the heat.

When we thought to look again, our hitchhiker had disappeared into the sand. And soon we pulled away, and the hot air around us began to move, and we felt something like the future prickle our skins.

~

The crew of the Enterprise, faced with the prospect of suffering interminable lab-rat losses at Nagilum’s hands, come upon what somehow seems like an obvious solution: They must initiate the ship’s auto-destruct sequence. Preferable to control their demise than have it thrust upon them. The sexless voice of the computer informs us the ship has twenty minutes until kaboom.

Nagilum is nowhere to be found. The Enterprise floats in silent ink.

Cut to Captain Picard, cut to our fearless Jean-Luc, spending his last moments draped over a recliner in his muted chamber. Classical piano music floats softly from hidden speakers. We zoom in on the captain’s face, zoom in on an eyebrow flicking.

The doorbell chirps. Enter sallow-faced Data, the ship’s android officer. Data is neither man, nor precisely machine; he wants, more than anything, to understand.

I have a question, sir, Data says, sitting stiff on a settee. What is death?

Picard chuckles paternally. You’ve picked probably the most difficult of all questions, Data. Some argue that the purpose of the entire universe is to maintain themselves in their present form in an Earth-like garden which will give them pleasure through all eternity. And at the other extreme, are those who prefer the idea of our blinking into nothingness with all our experiences, hopes and dreams only an illusion.

Which, Data presses, do you believe?

Picard considers. The camera zooms close enough to suggest wheels turning within his gleaming head.

I prefer, he says finally, to believe that my and your existence goes beyond “practical” measuring systems… and that, in ways we cannot yet fathom, our existence is part of a reality beyond what we understand now as reality.

Data cocks his head.

In that instant, stars appear outside the portholes behind Data. The Enterprise has been returned to normal space. Just like that. Just like that, they have escaped that which they could not see; Nagilum wanted to understand death, and Picard was close enough.

~

If what we were doing was mapping our future onto America’s highways, what bore a hole in our atlas was the failed attempt to unstick as well from the past. From a surgery. From a set of empty walls. Outside of Dallas, a terrible thunderstorm beached the Escort like a whale under an overpass. Outside of Las Vegas, an encounter with the potato salad at a Sirloin Stockade buffet left my parents and sister doubled over and fighting for the bathroom at a Red Roof Inn for two days, a sickness I avoided only thanks to a firm anti-slimy food policy. In the southwest, we stood in four different states and held hands in a sine wave of experience, my mother fretting about the possibility of heatstroke. At the Grand Canyon, my sister half-heartedly tried to push me in. At Crater Lake, two tame chipmunks hopped after us down the overlook path while my mother swung her purse at them, convinced they were rabid. At the Monterey Squid Festival, the La Brea Tar Pits, the redwood forests, at Disneyland, death clung to us like a burr, my father the only one who didn’t seem to feel it.

Look, girls. This is the world, girls. This is the world.

When we came home, my father covered the bones of our house with drywall skins, and we took back our positions for Saturday night Star Trek as if we’d never left. Time slipped under us until we blinked awake one day and it was the future. Because of that, I will finish season four and rent season five, then season six. Because. I will watch the Enterprise cheat death on a loop, and the harder I look, the more it will feel like a world I have seen before.

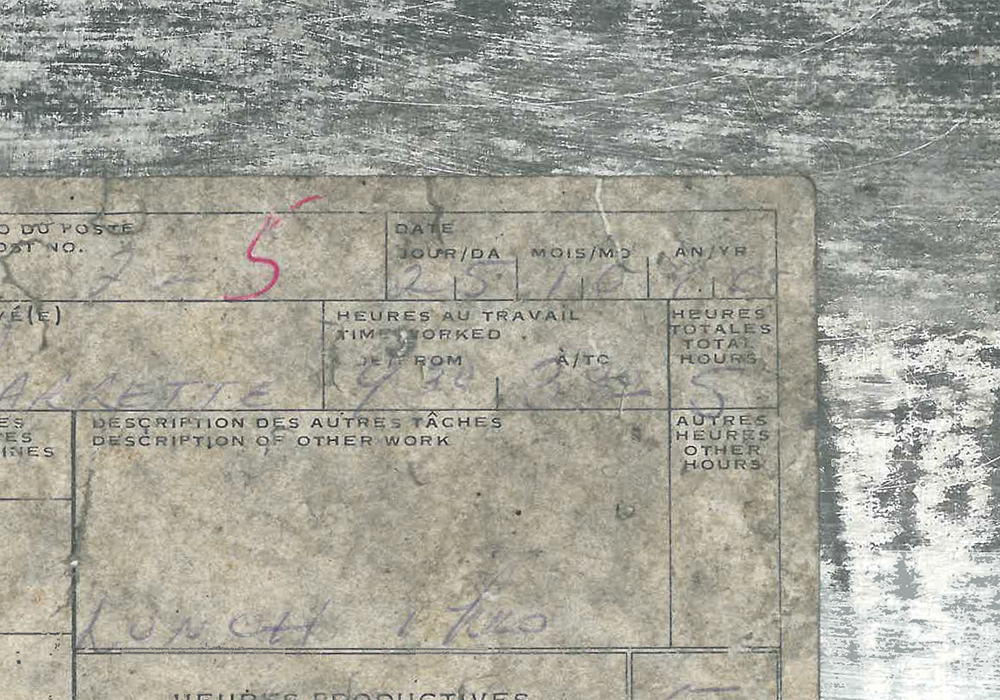

Art by Matt Monk

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#1f4378′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

[av_one_half first] [/av_one_half]

[/av_one_half]

[av_one_half]J.D. Lewis is a student in the University of Iowa’s Nonfiction Writing Program. She lives in Iowa City, where she works as a writing instructor and tutor at UI and as Art Director at Defunct magazine. Currently, her favorite president is Herbert Hoover.[/av_one_half]

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#1f4e78′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

jordan Sneakers | Nike Dunk Low Coast UNCL – Grailify