[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#1f4378′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

Meditate lying down. If it’s the afternoon, and the house is quiet, meditate on the red couch in the family room, and hope that it will lead to a little nap. Meditate with your dog. She’s always up for some Zen time, and often curls herself around your bare feet. You cannot be in the same vicinity without touching; your affection for each other is so completely and unconditionally mutual.

Practice Yin yoga. In Yin you hold postures and twists for 5 minutes. You hardly sweat and yet parts of your middle-aged body gradually soften, like frozen dough left on the countertop to thaw. Blocks and blankets and variations are encouraged. Anything goes. During Savasana place your legs over a bolster and cover your body with a blanket. Although you are in a roomful of people, notice how surprisingly peaceful this is.

If it’s the morning, meditate in bed. Stack some pillows against the headboard and semi-recline. Allow yourself breaks to sip coffee: Peets, Major Dickason’s Blend, steamed milk whipped up with your hand-held frother, one small tap of organic cinnamon, the Impressionists mug with flowers painted outside and in. As always, include the dog. She is accommodating. The dog will meditate at any time of day.

During yoga, when you are in postures that open the heart—a backbend or lying over a bolster positioned along your spine—you are often overcome with loneliness. It bubbles up from your belly and comes to rest under your sternum. It feels deep and old. After a while it passes, but makes you wonder what else your body has held onto over the years. Maybe your body is in possession of every single injury, every emotion you have experienced. Your dislocated shoulder, the argument with your co-worker in 1987, childbirth, the death of your father, may all be tucked away, folded meticulously like origami and stored away in your joints, under the sheaths of your muscle fibers, bundled around your kidney, blocking the right ear that you can’t hear out of anymore. You imagine all of your disappointments coiled snake-like into your intestines. Your fears—of heights, being held underwater, losing a child, being locked in a steam room, falling off the edge of the Grand Canyon, speaking in public, being poor, traveling out of the country, contracting ALS—all free float through your bloodstream, circling through you constantly, relentlessly, seeping into every cell.

When meditating, one is not supposed to think. But of course, the harder you try not to think, the more persistent your thoughts. Do not berate yourself for having thoughts, just observe them, notice them, and let them float by, like a slow-moving cloud. Even so, sometimes the entire act of meditation is one big frustration—some worries refuse to pass cloud-like, and instead meat hook to your brain and you’re doomed. Have a mini panic attack. Check the timer. Ten minutes of concentrated worrying is an eternity. The dog has no such difficulties. She might adjust her position, twist on to her back, for example, in hopes of a belly rub, but unless the UPS guy rings the doorbell, she’s already achieved nirvana.

Get a massage. When the therapist asks if anything in particular is bothering you, jokingly say everything. But soon after she places her hands on you, you realize it is true. There isn’t a place on your body that doesn’t feel acutely sore under her pressure. You hurt in places you didn’t even realize. You allow her to mine your pain. She digs it out between the vertebrae of your neck, underneath your scapula, in the joint capsules of your hips, hidden beneath your quadriceps. She finds all of it. When she kneads the web between your thumb and first finger you nearly leap off the table. What is that? Energy, she says, and works and works it until she feels it release. You wonder what she means by energy. You imagine this is where all your failures lie, large and small, woven into the pad of your palm.

You suspect your body has absorbed the good along with the bad. Somewhere hidden among your organs must be joy. There must be contentment, and brief flashes of peace. The fleeting but perfect moments, like the morning you drove across the Palm City bridge and the water below sparkled while Neil Young played on the radio. You had just driven through for coffee and hadn’t yet taken a sip. But you could smell it. You could anticipate the hot, bitter taste. Or how about that night flight to Boston when the girls were small? As soon as the plane lifted off they each leaned into you from their seats and fell asleep, and you closed your eyes too, and thought, if the plane went down into the Atlantic it would be ok because of the heaviness of their bodies, their warm weight against you, one sweet head in your lap, the other fitting exactly tucked into your chest. The exquisite perfectness of that was almost too much to bear.

Ask yourself why. Why do you make yourself sit still, to twist into shapes of loneliness, to allow someone else to touch your life experiences? You don’t know the answer. You only know that in the past you’ve distracted yourself—alcohol and sex and that tiny phase involving recreational drugs. You have eaten too much. You’ve eaten too little. You kept going when your body begged for rest. You’ve ferreted away feelings meaning to take them out and consider them later, another time, and then avoided the task or simply forgot. And so now you feel as though you owe it to your body, these small gestures. These acts of kindness. This is why you do what you do. To make room, to clear out a space, to unwind the tight loops of clutter so a memory of a long ago plane flight has a place to stay.

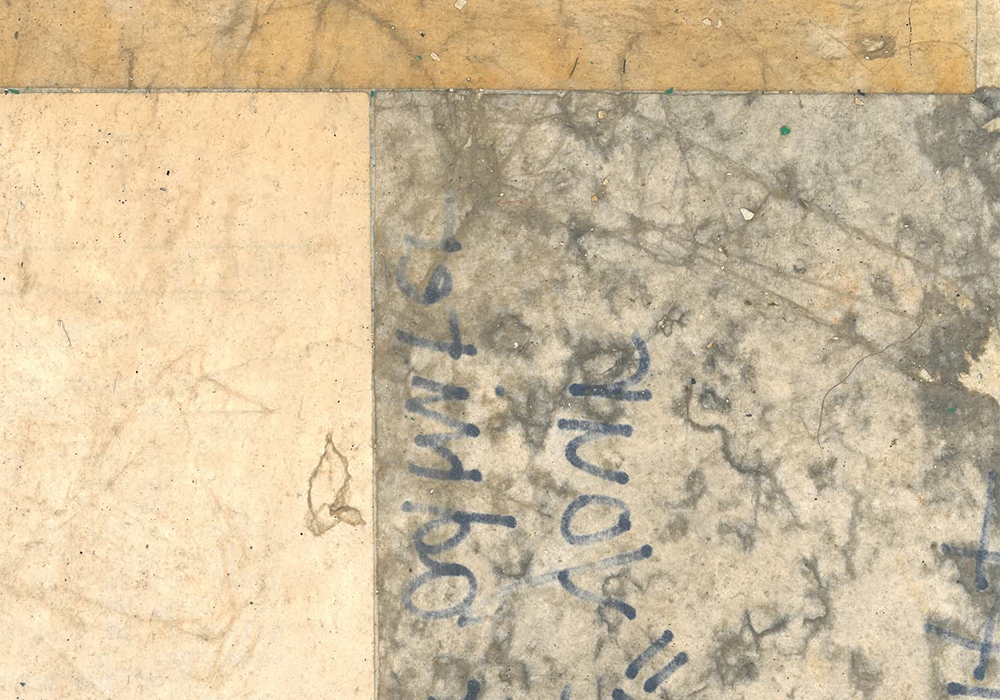

Art by Matt Monk

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#1f4378′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

[av_one_half first]

[/av_one_half]

Betty Jo Buro holds an MFA from Florida International University. Her work has appeared in Cherry Tree, Hippocampus Magazine, The Lindenwood Review, The Manifest-Station, Compose Journal, and Sliver of Stone. She was a 2016 finalist for Southern Indiana Review’s Thomas A. Wilhelmus Award, and a 2016 semi-finalist for American Literary Review’s Annual Creative Writing Awards. She lives and writes in Stuart, Florida.

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#1f4378′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]Nike shoes | Nike Shoes