Look! That picture book boasts a shiny sticker on its cover.

Study the sticker closely. Do you see a man bouncing on a horse? He’s John Gilpin.

Gallop back in time to meet the artist who drew him…

The world Randolph Caldecott loved was a leaping, flying, dancing, barking, galloping place.

At the King’s School in Chester, England, Randolph sat still long enough to pay attention, earning the title of Head Boy for his good grades.

The second school let out, he was off on adventures. On his way through town, he sampled sweets from the bakery, chatted with merchants hitching their wagons, and watched ducks splash in the River Dee.

He traveled the country lanes and fields, jumping over streams and fences. Randolph paused, every now and then, to study a pig’s snout, admire a rooster’s colors, or pet a farmer’s dog, but mostly, he was a kid on the go.

Those adventures whirled through his mind when he got home. He sent them sailing onto paper.

Mr. Caldecott didn’t encourage Randolph’s artistic talent. He wanted his son to be a banker. In 1861, at fifteen, Randolph moved to a nearby town to give banking a try.

Randolph added column after column at the Whitchurch and Ellesmere Bank. He needed a break from so many numbers! He sketched his fellow employees and the bank’s customers, a handy use for old deposit slips.

Luckily, his job included calls to local villages. He sped over the lanes in his brand new country gig. The villagers liked Randolph. They invited him to steeple chases, dances, and cattle fairs. More happenings to draw when he returned from the fun.

The Queen Railway Hotel caught fire that year. Randolph whipped out his notebook to sketch the shooting flames. He drew a more detailed picture later and mailed it to The Illustrated London News. The magazine sent Randolph a check, and, hooray, they published his drawing!

At twenty-one, he was promoted to a bank in the city of Manchester. Randolph grabbed the opportunities city life offered him: art lessons, an art club, and friendship with other artists.

Randolph suffered from a weakened heart and stomach pains, but he refused to let illness slow his artistic tracks. He snatched every spare moment to draw and paint. Sometimes, he even forgot to go to bed, working all night long.

But Randolph didn’t forget to celebrate each time he sold another piece of art.

One day he made a brave decision. He up and quit the bank.

Randolph Caldecott was on the move, this time to the great city of London. “I have enough money in my pocket sufficient to keep me a year or so,” he wrote to a friend. In that year, he would learn if he could make a living as a professional artist.

Talk about a hopping place! Randolph roved the streets and squares of London. He sketched kids rolling hoops, ladies selling flowers, and rich gentlemen strutting to the theater with their noses in the air.

Inside the theater, he drew Hamlet on stage with a sword in one hand and a torch in the other. He drew the Prime Minister giving an important speech at Parliament. And when witty Mark Twain visited from America, Randolph caught him on paper.

Randolph spent happy hours at the Zoological Gardens. He sketched everyone he met from the roaring lions to the zookeeper mucking out the stalls.

The animals lay stiller than still in the British Museum. Randolph studied the wing feathers of a stuffed stork. He measured the skeleton of another stork. He needed to understand how their bodies fit together and how they worked so he could bring animals to life in his drawings.

Project after project delivered money to his pockets. He painted huge swans for the dining room of a fancy house. He climbed high into the Harz Mountains to sketch the sights for a travel book. His big break came when he illustrated one hundred and twenty scenes for Washington Irving’s Old Christmas.

People were paying attention to Randolph Caldecott, including an engraver named Edmund Evans. Mr. Evans was experimenting with something exciting: color printing. Publishers sold books for older kids in England, but they didn’t offer many picture books, especially beautiful ones. Edmund Evans was determined to change that.

He visited Randolph in his apartment on Great Russell Street and asked him to create two picture books.

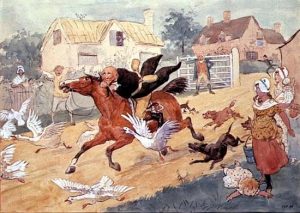

Randolph knew kids were cool. He jumped right into the project. He decided to illustrate a nursery rhyme, “The House That Jack Built” and a ballad, “The Diverting History of John Gilpin.”

First, he constructed a blank book in the size the real book would be.

Next, he figured out where to place the words and pictures. He made quick drawings called “lightning sketches” as he thought about the story.

Then he painted the actual illustrations with brown ink and a small brush.

Finally, he added color to some.

Mr. Evans printed 10,000 copies of each picture book in time for Christmas, 1878. The first printings sold out right away. Success! From then on, Randolph and Mr. Evans produced two new picture books a year.

Kids loved the books. Randolph didn’t preach or try to teach manners. The grownup characters made silly mistakes, and the kid characters got important parts. He even cast a boy and a girl as the King and Queen in Sing a Song for Sixpence.

And no one sat still. Cats caught rats. Frogs paid calls. Knaves stole tarts. A bear in a flowered dress and bonnet promenaded down the street. A doll danced. Dinnerware bopped to life.

Randolph didn’t fence his characters in with a black border like many illustrators did. His characters moved across the page as if they were actors on stage. He left plenty of white space, too, so they could breathe.

Randolph Caldecott became famous in England, Europe, and America. Not one to brag, he spoke in a low, quiet voice. He sported a pleasant expression, although it was hard to see because of his whiskers. Tall and thin, he sometimes put himself in his pictures. He married in 1880. Mrs. Caldecott began to make appearances in Randolph’s pictures, too.

No matter how busy he was, Randolph answered the letters kids sent him. “I thank you very much for the grand sheet of drawings,” he wrote one boy. “There are many beautiful things waiting to be drawn. Animals and flowers. Oh! Such a many.”

In 1885, a London magazine asked him to travel to the United States to record “American Facts and Fancies.” Randolph said yes to the adventure.

The rolling of the ship in rough seas was not the kind of motion he relished. He joked in a letter: “We hope an overland route is discovered by the time of our return.”

That fall, Randolph drew the people and sights of America, from a boy getting off the ship in New York to dock workers loading cotton in South Carolina.

The Caldecotts reached St. Augustine in December. Randolph was now sick, really sick.

The man who never stopped drawing kept on.

Then the lines in his sketchbook trailed off.

Randolph died on February 13, 1886. He was thirty-nine. His good friend wrote in a tribute, “The artist’s hand is still.”

Fifty years later, publisher Frederic Melcher created an award to honor picture book illustrators. He named it the “Caldecott Medal” after the artist who, with energy and enthusiasm, first captured for kids the scurry and frenzy and fun of the world.

Look at the Caldecott Medal. There’s John Gilpin on his horse, coattails waving as he gallops through town. Geese honk. Dogs bark. People hurry about. No one is sitting still. Randolph Caldecott, forever in motion!

***

Creative Activities to Use with Randolph Caldecott, Forever in Motion

For Teachers

Oh! Such a Many Journals: Randolph wrote in a letter to a boy: “There are many beautiful things waiting to be drawn. Animals and flowers. Oh! Such a many.” Have students fold five or six sheets of paper in half and then staple them together to make journals. Ask them to write “Oh! Such a Many” on the front of their journal. Inside, they can draw things they think are beautiful. Next to each drawing, ask them to jot down words describing that beautiful thing.

Objects to Life: Randolph was one of the first illustrators to bring objects to life in his picture books. Explain to children that this is called “personification.” Human qualities are given to things that aren’t alive. Next, ask them to find something at their seat to bring to life such as their pencil, notebook, friendship bracelet, or shoes. Through creative writing, drawing, or small group conversations, let students express what their object is thinking and feeling.

Lightning Sketches: Have students take turns choosing an animal or object for everyone to draw as fast as they can. Explain that Randolph used this technique when he designed a new picture book. Set a timer to add to the fun. Children sometimes have trouble with the concept of sketching. Help them understand that a sketch isn’t precise or detailed, but a useful tool for brainstorming and planning.

Capture That Scene: Randolph first earned money as an artist by drawing news events. Let your students bring pencil and paper out to the playground during recess Ask them to study the scene, as Randolph did, and then make a drawing of the playground action. Display the drawings in the hall for the rest of the school to admire.

Long Columns of Numbers: In honor of Randolph’s banking days, ask your students to create a long column of numbers. Have them switch papers with someone else and then add up that column. Randolph made sketches of his fellow bankers when he got tired of adding. Invite students to make a sketch of a classmate on their paper.

Travel Guide: Randolph spent happy hours exploring London. Use travel books and websites to show students the sights of London. Next, on paper or in small groups, have them list their favorite sights in your area. Let them each choose a sight to draw. Ask them to write a sentence or two describing their drawing. Put the drawings together to create a travel guide. Display the travel guide in your school media center or use it as a welcome gift for a new student.

Caldecott Medal Winners: Read Caldecott Medal winners and Honor Books to the class. Then go through the books again, examining the illustrations more closely (or have students do this in small groups). Randolph’s art was best known for its sense of motion and its humor. Ask students to look for those qualities in the illustrations and to share what they find.

Picture Book Party: Kids loved the picture books of Randolph Caldecott. Invite your students to bring in a picture book they love. Let them show the class their favorite page and explain why it’s their favorite. Then treat your students to a reading of your favorite childhood picture book. Consider playing a game or serving a snack in celebration of your book.

For Kids at Home

Clay Creations: Randolph made clay models of animals and other objects when he was a boy. To make your own modeling clay, mix two cups flour, one cup salt, and three tablespoons cream of tartar in a saucepan. Stir a tablespoon of cooking oil into one cup of water. Add several drops of food coloring. Pour the liquid into the saucepan. With an adult, stir the mixture over medium heat for a few minutes. Cool and then knead. Use your clay to create animals and anything else you like.

Action Charades: Randolph’s illustrations are alive with motion. Take turns acting out animal actions such as a duck waddling, a horse galloping, or a frog jumping, and people actions such as flying a kite, riding a skateboard, or licking an ice cream cone. The actor may not talk or make any other sounds. The other players guess the answer by shouting it out. Whoever guesses first gets a point.

Thank You Pictures: Randolph wrote lots of letters. He often included a drawing, signing his name “Pictorially Yours, Randolph Caldecott.” For your next thank you note, draw a picture of yourself enjoying the present you received. Add a simple “Thank you” and sign your name.

Cover Image: Caldecott, Randolph. Gilpin Losing Control of his Horse. Colored engraving. 19th century. Victoria & Albert Museum, London, UK.latest jordan Sneakers | New Balance 991 Footwear