Bill Kartalopoulos once lived in a large apartment in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, known as the Cartoon House. In 2012, VICE called the home “a giant flophouse where cartoonists live.” Cartoon House was full of goodies: crazy art on the walls; easels and cartoonist’s desks; a giant bubble-letter neon sign that read “CARTOONS”. It was a space where the big names in the art world often came to hang out and drink wine (or more likely, Pabst Blue Ribbon).

In addition to cartoonist parties, the space hosted numerous creative theme parties, including one inspired by the Harmony Korine film, Spring Breakers. I had the luck of attending a few of these soirees, which is how I first met Bill. He was always pleasant, seemingly unfazed as he spewed dry humor with ease. When I think of him, I imagine him as he looked then: clad in a sweater and circular-framed glasses, always appearing effortlessly cool.

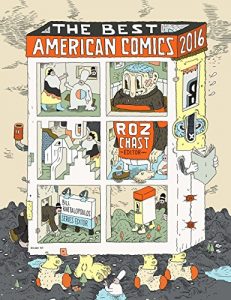

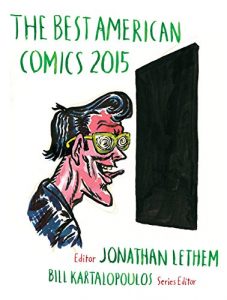

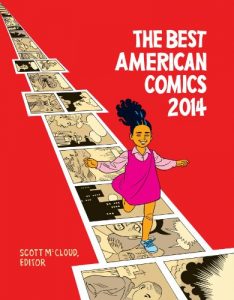

Kartalopoulos is a critic, teacher, and author, as well as the editor for Best American Comics, the #1 New York Times best-selling series published annually by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. In addition, he is writing a history book about comics to be published by Princeton University Press. Kartalopoulos has written on the topic of comics for publications such as The Huffington Post, Publishers Weekly, World Literature Today, American Book Review, The Comics Journal and others. He teaches Comics History in the MFA Visual Narrative program at School of Visual Arts, and Graphic Novels at Parsons’ The New School. Currently, he is the programming director for the MoCCA Arts Festival.

Kartalopoulos is a critic, teacher, and author, as well as the editor for Best American Comics, the #1 New York Times best-selling series published annually by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. In addition, he is writing a history book about comics to be published by Princeton University Press. Kartalopoulos has written on the topic of comics for publications such as The Huffington Post, Publishers Weekly, World Literature Today, American Book Review, The Comics Journal and others. He teaches Comics History in the MFA Visual Narrative program at School of Visual Arts, and Graphic Novels at Parsons’ The New School. Currently, he is the programming director for the MoCCA Arts Festival.

GT: Do you still live in the Cartoon House? I love that place.

Kartalopoulos: No, I left it about three years ago and it got turned into a nicer, more expensive apartment — like most places in Williamsburg.

GT: How did you become the series editor for the Best American Comics?

Kartalopoulos: The Best American Comics series has been running since 2006. It’s part of a bigger line of titles, such as Best American Short Stories, Best American Essays, et cetera. They all pretty much follow the same model where there are a series editor and an outside person who doesn’t work at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt who works on the books for a certain number of years but also collaborates each year with a special guest editor, typically a more well-known person in the field.

Matt Madden and Jessica Abel — a husband-and-wife team who are both comic artists but also teachers — had that [series editor] job for six years, but they left because they got a residency in France. I guess they recommended me to the publisher and I went in and interviewed. It worked out well.

Matt Madden and Jessica Abel — a husband-and-wife team who are both comic artists but also teachers — had that [series editor] job for six years, but they left because they got a residency in France. I guess they recommended me to the publisher and I went in and interviewed. It worked out well.

Working on the book has been interesting and enriching in a lot of different ways. It’s also a very visible project.

Comics can respond quickly to an event and communicate a response.

GT: What are the responsibilities of a series editor?

Kartalopoulos: The way these books work is that they each have an open submission process. There is an address that anyone can send work to. An author or comic artist can send their work in and it doesn’t matter if it’s been published or self-published. On top of that, it’s my job to, in essence, make sure that we get everything that we should be getting. So, in addition to the large volume of stuff that comes in through the open submissions process, I also do a lot of outreach.

If I see that an artist has posted something about a comic or zine that they have self-published, I may individually email them to ask them to send their stuff in. I spend a fair bit of time just looking around at comic book stores and comic shops to see if there is anything that is not in the submissions pile that I should have. I go to festivals and walk around and ask people to submit their work. I also talk to colleagues and friends who know a lot and they sometimes have been really helpful in recommending work that may not have been on my radar. So, I end up with a huge quantity of comics. I also look around online because there are so many people posting comics online. It’s not possible to keep up with all of it but I at least make an effort.

I spend a ton of time reading through the various works I’ve accumulated then I make a pre-selection of about 120 pieces that I think are the most outstanding pieces to send to the guest editor. Then, the guest editor makes the final choices about what goes into the book. They have some latitude, too, to bring in some material that they have discovered on their own. I’m always surprised in a good way to see the final choices the guest editor has made.

Once they have made their choices, then I have to reach out to all the artists and get preliminary formal permission to include their work in the book. I write a foreword to the book every year and the guest editor writes an introduction. I also compose a list of about 100 notable works that we also list in the book in addition to the work that we are printing. That is a place to at least mention the work that I saw and appreciated but didn’t make it into the final volume.

I also have to communicate with the art director at the publishing house and the designer. We deal with decisions that come up in the course of figuring out how to design and organize the book. We find an artist to draw the cover for the book. We’ll also commission some original art for the book, even though much of the art is already published.

GT: Are there any factors you consider when making your choices on the art?

Kartalopoulos: During my conversations with the guest editor, I try to feel out the kind of work they like to see and if there is anything, in particular, they are interested in so I’m not wasting their time.

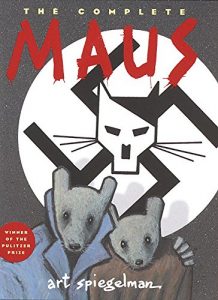

GT: What kind of influence does your past work with Art Spiegelman have on your work with Best American Comics today?

GT: What kind of influence does your past work with Art Spiegelman have on your work with Best American Comics today?

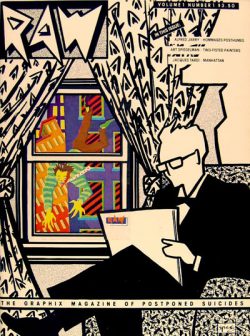

Kartalopoulos: Working with Art was a huge education because he has a real encyclopedic knowledge about comics. On top of that, he also has a really strong analytical and critical point of view. Spiegelman — together with his wife, Françoise Mouly, who is the art editor of the New Yorker (and has been since 1993) — edited in the eighties and early nineties a comics anthology magazine called Raw, which has a reputation for being one of the best comics anthologies of all time. They were very selective about the material that they chose and were attentive to design and presentation.

The standard that was exemplified in Raw persists in Art when he is looking at new work. He is always interested in knowing what is new in comics, but at the same time, he also has a real high standard for excellence. On top of that, Art works very hard; he has a perfectionist tendency towards the projects that he gets involved in. So, all of those things have, to a greater or lesser extent, informed a lot of the projects and work that I have gotten involved with.

Working with Art Spiegelman was a huge education because he has a real encyclopedic knowledge about comics.

GT: Tell me about your upcoming book.

Kartalopoulos: I’m writing a general history of comics for Princeton University Press, focusing on North American comics. It’s a book that is badly needed, I think. It’s something that comes out of my teaching. This book would certainly be useful for me to have in my teaching, but it would be of interest to general readers too.

There are a lot of books about individual subjects in comics that have come out in recent years, ranging from multi-volume reprints of well-known comics like Peanuts or Little Orphan Annie to biographies of comic artists, like the creator of Wonder Woman.

There are also a number of books about specific subjects such as American comics in the 1950s. The list goes on. But there isn’t a Comics History 101 book for someone who just wants to understand the broad overview of the story and to see how all those other pieces fit together in a sort of narrative. So it’s a little backward, in the sense that we have all these very specialized books, but we don’t have a book that should function as a starting point.

GT: Why are comics so important right now?

Kartalopoulos: There are a lot of reasons why comics remain relevant. For one thing, I think they are unlike a lot of other visual media — ones that require budgets; a lot of people; access to technology, or all of the above. Somebody can make a comic with pretty modest means. It does not take a lot to make a comic. It’s basically just pen and paper. In theory, you can do anything with that. You can create an entire visual world that way, whether it’s a personal world or a fantasy world.

I also think that we live in a visual culture. I don’t really think comics are necessarily on the cutting edge of that visual culture like they used to be because technology keeps moving forward. I think that comics at one point seemed like a step beyond prose towards a more visual narrative, but now we have so much video and interactive online content. Comics start to look more traditional somehow by comparison.

I also think that we live in a visual culture. I don’t really think comics are necessarily on the cutting edge of that visual culture like they used to be because technology keeps moving forward. I think that comics at one point seemed like a step beyond prose towards a more visual narrative, but now we have so much video and interactive online content. Comics start to look more traditional somehow by comparison.

Comics take a bunch of images and put them together in a coherent and articulate way, where you go from image to image, and from text/image combination to text/image combination. Then you look at it all and it all adds up to something. If there is an intelligent cartoonist at work then there is a design behind it all. By the time you get through reading it you can comprehend the design and see that there is maybe a larger concept behind it. I think that that in a way is almost like the equivalent in poetry relative to our visual culture, which is so incoherent. We just go from web page to web page, from video to message, from this to that to the other thing. You can get really drowned by this mosaic of stimulation over the course of the day as you consume media, but by the end of the day, it may not add up to anything or you may have to struggle to make it add up to anything.

It does not take a lot to make a comic. It’s basically just pen and paper. In theory, you can do anything with that.

I feel like comics process all those elements and present them in a coherent design. It models a deeper understanding of fragments of text image combinations. I think, from a media studies point of view, there is something to that because it is a very direct medium and should have an ongoing grassroots appeal as a way to express oneself visually.

GT: How can comics be utilized in our current political climate?

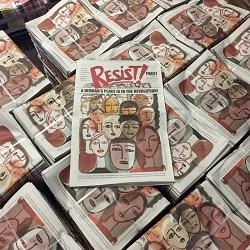

Kartalopoulos: There is a newspaper that just came out called RESIST! that was edited by Françoise Mouly and her daughter, Nadja Spiegelman. It was full of comic strips and cartoons — mostly drawn by women — initiated after the presidential election and published in Time for the Women’s March on Washington. They made thousands of copies of it and gave it away at the March. That shows how comics can respond very quickly to an event and communicate a response, a point of view.

Other work can be much more considered. There’s an artist called Joe Sacco who creates book-length journalistic comics. He goes to war zones, and has been in places like the former Yugoslavia and Palestine, and has created these very journalistic research-based projects where he interviews a lot of people, does a ton of research, takes photos and creates sketches, and then goes home and works for years to produce hundreds-of-pages books about a subject.

That certainly does not permit an instantaneous response like the newspaper I was just talking about, but there is a lot of value to that work because it shows something about how long comics can document something real, true and important in a way that other media can’t. He can put the reader in places where the camera can never go. He can present these characters, real individuals, in a way that represent their points of view intimately. It’s closer to the way that a writer would work, but he is able to provide visuals in the manner of a documentarian without the need to provide the kinds of happy accidents that make a good documentary.Sports brands | Nike News