[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#372a55′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

I.

Kazuo Ikeda’s first and last taste of fugu had been the spring he turned seventeen. Seventeen was practically adulthood. Kazuo’s goals for his adult self were:

- Do something interesting. This did not include camping in the car amongst redwoods with his parents; eating salted toffee while visiting historic Old Sacramento and nearly as historic old relatives; or catching the cable car to Fisherman’s Wharf only to end up overstuffed at Ghiradelli Square.

- Interact with a girl.

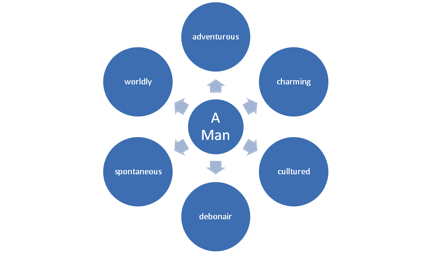

- Become a man. A helpful diagram:

Another way to chart it would be simply to frame a picture of his grandfather Masayoshi, who was up from Los Angeles for a few days’ visit.

His goals seemed causally linked. Doing something interesting would make him more of a man, which would make him more desirable to the opposite sex. And Kazuo knew just the thing: he would eat pufferfish. It struck just the right note. A cultured carelessness, weighing his very life against the pursuit of pleasure. Filleting open the underbelly of fear itself. And unique because San Francisco had just opened its first restaurant where fugu was legally on the menu—“Tora Fugu,” meaning tiger blowfish. Even its name sounded fierce, masculine.

Here was where Grandpa Masa was key. Grandpa Masa wouldn’t tell him Tora Fugu was too fancy. They wouldn’t end up, after exhaustive debate, at a tourist-trap restaurant in Fisherman’s Wharf. And Grandpa Masa did not disappoint him; in fact, he upgraded Kazuo’s dream.

“Of course you can get fugu in the U.S.—San Francisco, New York, L.A., et cetera, et cetera—but it’s not the same, ne, Kazuo-san?” Grandpa Masa’s tone was a pat on Kazuo’s head, but Kazuo beamed at the respectful “-san.” Although it had been tacked onto his first name instead of his last, which docked a few points of respect from the greeting, “-san” was still infinitely better than “-chan”—a notable upgrade from Grandpa Masa’s last visit.

“Totally. What’s the point,” echoed Kazuo.

Masayoshi’s son and daughter-in-law were hiding their smiles. Masa saw all of this—Kazuo’s eagerness, his parents’ amusement, that they had raised the boy so weakly that he grasped onto anything stronger to emulate it. It was up to him. The boy was already sixteen. Masa hoped he wasn’t too late. He should have visited more. Kept a closer eye on things. “I’m taking him to Japan,” he announced. “For his seventeenth birthday. We are going to eat real fugu.”

One month later, Kazuo found himself on board the beautiful bulk of a triple-seven. Because of Grandpa Masa’s many years as a pilot with JAL, no amenity was denied them. They’d waited in the VIP lounge, where Kazuo drank his cola from the same kind of tumbler in which Masa was having his whisky. “Don’t worry, boy,” said Masa, dismissing Kazuo’s drink with a royal wave. “When we get to Japan, they’ll be less strict.” As business-class passengers, they preboarded shortly after midnight, bypassing the bedraggled-looking people crowding the entrance to the jetway. “Excuse. Excuse!” muttered Grandpa Masa, elbowing his way through. Kazuo felt the mere act of passing the others made his body a big smirk, so he inclined his head, walking in a perpetual bow. He sympathized with the obasans and those with infants wailing, but his posture straightened as they went down the jetway because Kazuo loved airplanes. He loved everything about them. He loved their sleek aerodynamic bodies, the improbable alchemy that turned three-hundred tons of metal into a graceful bird. He loved the science of the planes, their symmetry, the anatomy of their airfoil wings deflecting air toward the ground, keeping the plane aloft. He wanted the world below, in miniature.

Masa was encouraged by the sound of the boy right on his heels. His grandson refused a steward’s help with a capable “I can manage” and stowed his own bags. Pausing at the third row, Masa offered Kazuo the window seat, and the boy refused mildly but then took the seat after Masa insisted. Good. None of that wishywashyness of the boy’s father. He had gone wrong somewhere with that one. He preferred to think of Tadao not as his son but merely as Kazuo’s father. He preferred not to think of Tadao at all.

Kazuo sat at the window, peering out. In the dark, he could barely make out the figures of the men down on the ramp, loading luggage into the bowels of the plane. He wished they were taking a daytime flight, because he knew once they were airborne, the lights of California would recede quickly, replaced by the wide expanse of the Pacific. Eleven hours of unrelenting ocean, all of it plunged into the ink of night, the next sighting of land in daylight likely Japan itself. Or so he’d read.

“Kazuo, you want something to drink?” Masa had flagged a flight attendant while they waited for take-off—the palest and most pretty, with her shock of short jet-black hair. But the boy hadn’t heard, hadn’t noticed—he was entranced by something outside the glass. “What are you looking at?” asked Masa, touching his grandson’s shoulder.

Kazuo startled, turned, reddened. “Some water. Please. I mean, hi, thank you.” What was customary? Were you supposed to treat a flight attendant like a professional doing her job or pretend she wasn’t serving you and was just a friend, doing you a favor? Kazuo, in business-class now, didn’t know—it seemed like a foreign country already.

“So, what had your attention there?”

“Oh. I was just watching them load the plane.”

“Your father’s not working tonight, is he?”

“No, no. He’s off. Home, I guess. With mom.”

“Wouldn’t that be funny? If you and I were sitting here while your father weight-and-balanced the plane? Don’t screw up, Tadao. You’ll wipe the Ikedas clean off the map!”

“Dad never screws up, though.” Kazuo was surprised by the slight edge to his voice. For the first time, he wondered what his father felt when Grandpa Masa was around, constantly disapproving of him. He was ashamed that it was the first time he’d really thought about it, but he also hated that his father inspired pity. “People”—he said, meaning his grandfather—“think Dad just puts bags on the plane, you know, but it’s much more than that. The math of balancing bags, cargo, passengers and pilots, equipment, fuselage … it’s intricate.” As he said it, he realized how much he meant it. His father’s job was behind-the-scenes, perhaps, but it was important. Grandpa Masa was looking at him strangely—perhaps he was rambling. He felt scolded. “Anyway. Dad’s really good at what he does. His coworkers even call him on his days off to get his advice about loading.”

The flight attendant came back with Kazuo’s water and a glass of red wine for Masayoshi. Masa thanked her and swirled the glass a bit, dipping his nose deep into the fine plastic. Almost like a real glass. He sipped at it slow, letting the wine live for a moment in his mouth while he measured his words. He had upset Kazuo, which he hadn’t meant to do. While he admired the quick way his grandson’s temper had flared, he was also alarmed at the precision with which his grandson understood and seemed to admire Tadao’s job. “You certainly know a lot about it. You gonna follow in his footsteps?”

“No,” said Kazuo because he knew that was the right answer. And then “no,” again, because it was true. “I want to be a pilot.”

“So, in my footsteps then!” boomed Masayoshi. Pride was swelling inside him and he didn’t know where to put it. He clapped the boy a bit too hard on the shoulder. “This is excellent. A pilot,” he said, his voice taking off and trailing. He tried to picture Kazuo as a grown man in the starched shirt and black uniform, the gold-accented pilot’s cap at a jaunty angle, just so. The pale and pretty stewardesses with their silk neckerchiefs and their soft little hands covering their giggles. Paths clearing before Kazuo because he was an important man, he flew planes, he was a hero. But Masa could not. Even in his mind’s eye, all he could see was a boy in a suit too large. Nevermind, nevermind. Kazuo could grow into it. “A pilot. This is a good job. This is a good goal, Kazuo.”

The abrupt clank of metal signaled that the hatches were closed, and now came the warm rumble of the huge engines. Kazuo felt it in his seat as much as heard it. His whole self felt like humming. He had a good goal, a good dream job. Grandpa was impressed. Kazuo was also impressed. He’d never put it into words before. He had always been drawn to planes, and his father’s own profession ensured that talk at home revolved around the airline industry. But he hadn’t thought—well, and there it was. A dream. If you want something badly enough, you will get it, his father always said. Kazuo could see it now. He saw himself in the cockpit, gazing out the windshield of the plane, the land quilted below, asphalt runway, then miles and miles of patchwork blues, the colors becoming more vivid, deepening, as his plane soared out over the Pacific. He visualized the flight instrument panel, a dashboard of hundreds of buttons and levers, blinking lights and notifying beeps, and the version of himself in the crisp white shirt with black-and-gold epaulettes knew what each one meant. He watched his grown self—who had taken on the compact, stocky stature of Grandpa Masa, the same decisiveness in every movement—talking easily and laughing with his co-captain. He saw himself cock the captain’s hat and straighten the black tie, heard himself announce, “This is your captain speaking …”

The lead flight attendant brought Kazuo back to business class, beginning her safety briefing with an elegant buckling of a seatbelt, clicking the parts together near-soundlessly and pulling the belt tight around thin air. Grandpa Masa was pulling out the sleep socks and eye mask from the first-class bag. But Kazuo wasn’t tired at all. How could he be? He didn’t care how long the flight was, he wasn’t going to miss an instant of this. It was his first international flight. His first triple-seven. His first solo trip with his grandfather. And somewhere in the air, high in the arc between San Francisco and Tokyo, he was going to turn seventeen. Kazuo imagined he was standing on a precipice, heels on the ground, toes in the air, and all around him he could hear wind whistling, the blue sky cut only by contrails, and any single thing might be the thing to put him over the edge.

II.

The phone rang. Kazuo rolled his chair over from where he’d been checking en-route weather conditions and answered it the way he always did. “Hai. Japan Airlines Flight Operations.” It wasn’t a question. He was unconcerned with labyrinthine levels of Japanese politeness. Anyone calling would be American, anyway, and calling with a job for him to do. He just wanted to get to doing it. He was a precise man, from the top of his head, which grew obedient hairs that lay meekly on his head and were trimmed every four weeks, to his meticulous Windsor-knotted tie and his unembellished black leather belt, to the tips of his spotless black leather shoes.

“Did you know that 60% of people who eat tainted fugu die?” The caller was male. Kazuo did not recognize the voice.

Kazuo thought he must have misheard, so he asked, “Pardon?”

“Fugu. You know, pufferfish. Particularly torafugu, Tiger blowfish. It’s a killer. Yet 10,000 tons of it are consumed each year. 10,000 tons of potentially fatal fish—can you imagine?”

“Ahhh. Yes. Strange. But, sir, I think you have the wrong number.” Kazuo replaced the receiver. Prank caller, he decided, probably some kids surfing the web and randomly dialing for kicks. He recorded the call in the company call log, though, noting:

Call received by: Kazuo IkedaOn telephone #: ___________ Date/time received: December 6, 2007, 10:35 PMSubject: Wrong number?Memo: Male caller. Probably wrong number or prank caller. Kept talking about pufferfish.

He recapped his pen and placed it neatly next to the call log. The teletype printer began spitting out the latest NOTAMs. He stood in front of the printer, waiting for the pages to finish, the planes outside taxiing in the dark. It was his favorite time—the quiet of the empty office, checking weather, checking route maps, receiving intel from Japan’s flight dispatch center. There was only the quiet hum that precedes the rush of his evening. He had been with the company for fifteen years, which at this point (having turned thirty-five) was almost half his lifetime, and he was devoted. He liked having something larger to belong to, a team of people, all working myriad jobs to ensure that all three-hundred passengers took off, remained airborne, landed safely, with maximum comfort and efficiency, while delivering profit to the company. He liked being part of a team—even, or perhaps especially, being the one to whom his co-workers turned. It was always “Kazuo! I need help with the watercooler…” or “Kazuo-san, how do I make a formula in Excel again?” or “Kaz. Man. Could you work my graveyard next week? It’s my boy’s birthday. I’ll get you back later.” They never got him back later, of course. He flipped jugs onto water coolers, made elaborate and stunning Excel documents, took graveyard shift after graveyard shift, and they just took the credit or took the time off with their kids. But it didn’t matter. Kazuo felt good—here he was, staring out into the dark, planes taxiing before him as if he’d summoned them. He imagined himself a conductor in a tuxedo, standing on high before an orchestra of planes. Everything poised for flight, for adventure, for greatness, but subject to his baton.

The phone rang again. Kazuo hurried back over to his desk, catching the phone on its fourth ring. Before he could say anything, the caller spoke.

“I was afraid you weren’t going to answer.”

“Ah, yes.” Kazuo’s face flushed with embarrassment, he scolded himself for daydreaming on the job. “Sorry. I was in the middle of something.”

“It’s okay. I know you’re busy. I don’t mind waiting.”

A pause. It wasn’t unpleasant. There was something companionable about this unrushed lull in conversation on the phone in the middle of the night.

Kazuo checked his watch. “Sorry, but … who did you say you were? And what can I do for you?”

“Actually, I didn’t say. But you know what I want.”

Kazuo waited for the caller to elaborate.

The caller didn’t.

“Sorry, sir. It’s been a long night. What did you want?”

“Fugu. I want to talk about fugu.”

Another slight pause now, during which Kazuo understood that what he thought was companionable silence had been nothing more than him recognizing the voice from the earlier call.

“I was telling you about the 10,000 tons consumed every year when we got disconnected. I’ll assume we got disconnected and not accuse you of hanging up on me. So. The poison in fugu is called tetrodotoxin. Such a sharp word. Like a knife’s edge. A substance 10,000 times more deadly than cyanide. Strange, don’t you think, that connection: 10,000 tons consumed; 10,000 times more deadly?”

Kazuo picked up the call log.

Call received by: Kazuo IkedaOn telephone #: ___________ Date/time received: December 6, 2007, 10:40 PMSubject: Prank caller? Memo: Repeat offender: same man who called earlier tonight. Caller intent on communicating that pufferfish is (a) very deadly and yet (b) very popular.

“Are you still there?”

Kazuo hadn’t realized it, but he was holding his breath. He let it out, slowly. “Hai. I mean, yes, still here.” Almost involuntarily, he added, “Sorry,” then cringed. His co-workers were always telling him to stop apologizing for everything, and here he was, on the phone with a prank caller apologizing for breathing. Or, more accurately, for not breathing.

“Thought I lost you there again. That we’d gotten disconnected. That would be unfortunate. Disconnection. It can be so abrupt. One minute you really think you’re getting through to someone, so … thoughtful is their silence; the next minute you realize you’ve been disconnected for a good 45 seconds and you’ve been sitting there talking to yourself … I’m not talking to myself, am I? You are still there?”

“You can’t see it, but I’m nodding,” said Kazuo.

“Ah, good. I’m glad,” said the caller.

“So. Tetrodotoxin,” Kazuo prompted. “You were saying?” He knew he should hang up the phone. The man was wasting his time, and Kazuo had an important job to do. It was his responsibility to brief the pilots, notifying them of the flight path chosen for them, taking into account inclement weather as well as a variety of other factors. Still, he couldn’t shake the companionable feeling. Kazuo told himself that a few minutes for a phone call wouldn’t set him back with his work. He was bored tonight, and he had hours to finish preparing his brief. Anyway, wasn’t it for just this kind of thing that he always worked so diligently—for the occurrence of the unforeseen? He was gathering more intel, that was it. For the call log. So his bosses would have a complete record.

“Tet-tro-do-tox-xin.” The man’s voice caressed each single syllable. Kazuo mouthed the word, noting the light, quick touch of his tongue to the roof of his mouth on the t’s and the d’s, feeling how the first and last syllables pulled his face into a smile, or a grimace, whereas the middle syllables puckered the mouth, expelled staccato breath. “It is what voodoo practitioners put in their potions to reduce humans to zombies. It’s completely deadly, yet the demand for fugu rises to the point that the fish is now endangered.”

Kazuo chuckled.

“What’s funny?” asked the caller.

“Ironic, isn’t it? A fish naturally equipped with a defense mechanism that ends up being endangered because of it?” He laughed again, and the sound echoed awkwardly. “I’m not talking to myself now, am I?” asked Kazuo. “You’re still there? We didn’t get disconnected?”

“I’m here. But we did get disconnected. Ironic, you say?” The man’s voice has risen in pitch. There was a deep breath drawn. “I don’t think you’re getting the point, Kazuo.”

And in a beat, the intimacy was stifling.

As if the man could hear Kazuo’s thoughts, he repeated his name. “It’s not funny, Kazuo. It’s not ironic. It’s death by pufferfish. It can take anywhere from twenty minutes to eight hours to die. It’s all but unstoppable once begun. At thirty minutes, the fugu eater feels weak, dizzy.” The caller’s voice picked up urgency as he went, moving faster now, a crescendo in volume, breathing shorter and more rapidly between words. “He senses a tingling in the mouth that quickly gives way to numbness. The paralysis spreads. The eater goes into convulsions. Airways no longer work. Breathing becomes constricted. Until, finally, the eater dies of respiratory failure.” The man flung this last line out as if he’d been climbing toward and finally arrived at an ecstatic height. “What a way to go, eh Kazuo? And yet still you Japanese fuckers eat the stuff. I can’t fathom it. But what can you expect from a nation that invented the kamikaze, the young man who’d offer himself to the Emperor for the opportunity to live like a cherry blossom in spring—a life made more beautiful by its brevity. If nothing else, Japan knows its Russian roulette.”

He heard a click—a tongue against teeth? Perhaps in imitation of a cocked and pointed gun? But then there was the busy tone. The caller had hung up on him. He froze, still holding the beeping phone, then slowly replaced the receiver and reached for the call log. His pen poised above the pad, he paused for a moment, gathering his thoughts before putting the pen to paper:

JAL employee on shift kept caller on phone for approximately fifteen minutes in order to better ascertain his intentions. Caller’s intentions seem exclusively to be cataloguing how pufferfish’s poison (tetrodotoxin) can kill. Further development: Caller knows JAL employee on shift’s name. How did caller know this employee would be working this shift? Why did caller target employee? At approximately fourteen minutes into the phone call, caller employed racial slur “Japanese fuckers.” At approximately fifteen minutes, caller hung up on employee.

Kazuo recapped his pen and laid it down neatly next to the call log. He didn’t know what else to do.

III.

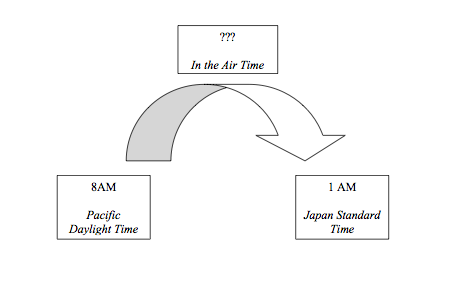

But of course eleven hours is a long time, and you can only watch so much air pass before you get bored, so at some point in the middle, Kazuo slept. It was only when he felt the slight bump-bump-bump and the headlong rush of the plane fighting its brakes that he woke. He hadn’t meant to fall asleep, and he certainly hadn’t meant to stay asleep so long that he missed the turning moment from sixteen to seventeen. It would have been at 8 AM PDT, which was midnight Japan Standard Time the next day, more than two-thirds through their trip, the Aleutian Islands somewhere far below, concealed under multiple strata of clouds. Kind of confusing, actually. He could compute the exact moment that he turned if he were grounded anywhere in the world, but high in the undemarcated air, in no timezone, he was neither here nor there. Kazuo carefully diagramed the process

TIMES AT WHICH KAZUO WOULD TURN SEVENTEEN

Had he been awake, would he have been able to feel the exact moment that he crossed that nebulous border between the years? He had arrived, but he didn’t feel any different. And like the plane balking at its brakes, he was disappointed to have landed. He wanted still to be in the air, the world below, in miniature.

“You missed breakfast. Here.” Masa, who’d woken hours before, handed Kazuo a dry bagel, a small container of grape jelly, and an apple. His grandson barely seemed awake and was frowning. “It doesn’t matter, Kazuo. We’re going to eat soon, anyway, and it will be better than airplane food.”

Grandpa Masa and Kazuo took the JR East Sōbu Main Line to Masa’s favorite restaurant, where the chef came from a long line specially apprenticed in the art of fugu preparation. Tucked deep in back-alley Sumida, Tokyo, the restaurant was in a residential area far from the neon-lit, speeding Tokyo Kazuo had imagined. Grandpa Masa strode down block after block, never consulting a map, as if the route was programmed into him. They turned the corner onto yet another street, this one eerily devoid of people, lonely. He wondered if it was such a good idea to pick a restaurant in such a desolate area, but he trusted his grandfather, and his grandfather evidently trusted this particular chef—trust was the thing when it came to fugu. You were placing your life in another’s hands as surely as if you were selecting a heart surgeon.

Before entering the restaurant, Masa lifted his head, noting the towering cumulus sitting heavy and grey above, reading them with his pilot’s eye as portent of imminent thunderstorms. It would be a bad night to fly. In fact, it was the kind of evening for scotch to warm your belly, for an early night with a good book, but instead he was here, entertaining his grandson. “Never mind, never mind, boy,” he said, clapping Kazuo roughly on the shoulder and pushing him through the door of the tiny restaurant. The air was still inside, and the long pale polish of the sushi bar empty. No doubt the would-be patrons were tucked in with their own scotches and books, or beers and TVs. Masa pursed his lips, and right then heard a firm “Irasshaimase.” A kimono-clad young woman had materialized to seat them.

Following her, Kazuo whispered: “You’ve been here before?”

“Many, many times,” said Masa. “Namba-san is one of the most talented chefs in all of Japan—especially when it comes to fugu.”

“Are you sure …” Kazuo trailed off into the room, which seemed to him as empty and somber as a tomb. He cleared his throat and began again, “It hasn’t, um, changed hands or anything, has it? I mean, where are the other customers?”

Masayoshi felt an undignified and uncontrollable urge to giggle. It was rising in him, high and fast, like effervescence in champagne. It wouldn’t do, so instead he barked out a laugh. The girl blushed and bowed with embarrassment to Masa. Ah, he must have startled her. He hadn’t noticed. Anyway, the blush looked good on her, cherries on the snow-white of her cheeks. He straightened out his face to reply to Kazuo, “Probably the weather … Or perhaps chef has killed them all.”

Kazuo’s head came up sharp, only to see Grandpa Masa had been staring at him. Grandpa Masa had been teasing, but the tilt to his head seemed pitying, perhaps even repulsed.

“You really are a … how do they say, Nervous Nellie, aren’t you?” His grandfather barked again.

This time the pretty waitress did not flinch. She indicated that they should enter a room lined with tatami mats and sequestered by shoji screens. She presented the menus. “No, no, no,” said Masayoshi, waving the menus away.

Grandpa Masa let loose a long and fluid discursive in Japanese. Kazuo caught none of it, anxiously noting the disappearance of the menus with the girl. So much for being treated like a man. He wasn’t even going to be allowed to order for himself.

As soon as the girl left, Grandpa Masa leaned in to say, “Pichi-pichi, eh, Kazuo?” From the arch of his grandfather’s eyebrows, Kazuo read that he should have been attracted to the young hostess.

“What exactly is pichi-pichi?” asked Kazuo, in hushed murmur, leaning in toward his grandfather.

“Fresh and young.” Grandfather’s voice was low like his but more husky. “Ready.” Kazuo’s mind rewound quickly to the moment they had entered the restaurant—her disembodied firm greeting, then her tiny stature and the black of her hair and kimono highlighting the white of her skin. As she’d led them to be seated, her legs constricted by the tight column of kimono and feet hobbled by the high geta, her eyes properly looked down, demure. This was what Kazuo should like. Three more kimono-clad women materialized a few minutes later with dishes of food, tall, sweating water glasses, and cups and a strangely shaped teapot. From each plate glistened the unknown, and Kazuo’s insides began to flutter. As soon as the women left, Kazuo reached straight for the teapot and cups. “Grandpa, may I serve you some tea?”

Masa snorted, he couldn’t help it. “Kazuo-chan, that isn’t tea … it’s sake. I mean to make it up to you—seventeen years of having my son as your father. Clearly I’ve got my work cut out for me.”

Kazuo was growing increasingly bewildered by his grandfather’s hostility. “Sake, then,” he said, trying to tough it out. “Grandfather, may I please serve you some sake?”

“Okay, okay. I’ll take some sake, boy,” Masayoshi said, accepting the cup from Kazuo.

Kazuo then poured himself a cup, mimicking how Grandpa Masa held the tiny cup in his right hand.

“Kampai!” said Masayoshi.

“Kampai!” replied Kazuo. He moved the cup quickly to his lips.

“Slowly, now, Kazuo. Don’t down it like a shot. Sake must be sipped slowly. It must be savored,” cautioned Masayoshi.

“Okay, okay, okay,” said Kazuo.

Masayoshi brought his cup to his lips to hide his smile. Kazuo had timed his own first sip to his perfectly. The boy took the drink like a man—this heartened him. There was still time to salvage things. Slow and steady, he reminded himself. Be gentle. Then he pushed forward a plate of fugu-sashi, sliced so paper thin that through its flesh the blue-and-white floral design of the dish itself was visible. “Note the arrangement, Kazuo,” Masayoshi prompted. “They lay the sashimi just so, in overlapping rings like this, to suggest a chrysanthemum. The flower of death,” he snorted. “No one can say Japanese lack a sense of poetics.” A giggle threatened to escape again. The sake seemed to be going to his head fast—he shook his head to clear it. On the plate in front of him was nigiri-style fugu, slightly thicker slices of fish, served sushi style, minus the nori. The plate was garnished at its edges with yubiki, a salad made from the fugu’s skin. The pale pink flesh glistened as it bent delicately over well-formed beds of rice, not a grain out of place. “Ahhhh,” Masayoshi sighed, gazing at the dish. “Fugu is one of the most exquisite things we can eat. It is the one food denied to the Emperor of Japan, no matter how he begs, for his own safety, but it is something you and I—common men—can, of our free will, partake in. It is so beloved by us Japanese, despite being essentially a poison rendered inert. See that color?” His grandson nodded. “Like the inside of a shell.” He sighed. “Very fresh.”

“Pichi-pichi,” piped up Kazuo.

“Yes, good, Kazuo. Fresh and such a gorgeous pink. The pink is less vivid when it is farmed, as they do in the U.S.,” he said, his distaste written in the savage curl of his lip. “See how tender?” Grandpa Masa gently nudged the flesh with one chopstick, and the fish trembled before them. “It is soft like the skin of a woman …” He trailed off. “Anyway. Eat.”

Kazuo eyed the plate, aching with the desire to impress his grandfather and with the fear of putting something in his mouth that did not belong there. “But, Ojīsan, if it is poison, why eat it?”

“Ahhhh, yes, Kazuo-san, this is the question, ne?”

Kazuo beamed.

“Squirrels avoid red berries. Birds eschew colorful bugs and frogs. The fittest species have always been the ones that ate the brown and the gray. But we Japanese are so foolish. We scorn fear and welcome risk. We eat for the pleasure of the delicate sweetness on our tongue, the firm yet subtle flesh, the rich complexity to be had. We eat to embrace umami, the fifth taste, savory, mythically, mystically, unbelievably, indescribably delicious. We eat for the chef’s aesthetic skill in presenting us a deadly predator as our meal, and his technical prowess in rendering the poisonous flesh just poisonous enough to still give a pleasurable tingle to the lips and tongue, like an aphrodisiac. We eat to embrace the forbidden, to hold it as intimately as we would a lover. We think what is life if you avoid beauty?”

Grandpa Masa’s reply, while poetic and philosophical, had not really answered Kazuo’s question. The fish was pale and soft. It seemed innocuous, but he had read that even the smallest pinch of this poison—the size of a match head—was lethal. Still, his grandfather was waiting, so Kazuo picked up his chopsticks. He plucked a nigiri-style fugu from the plate and placed it in his mouth like his life depended on it.

IV.

It had been an hour since the pufferfish caller hung up on him, and Kazuo was still out of sorts. Why hadn’t the man called back? He had assumed that there would be some closure, some explanation for this intrusion of absurdity into his evening. None came. He had assumed wrong. The phone remained silent. Who was the caller? Should he have recognized the voice? What did it all mean?

Why, of all things, did he call to talk about pufferfish? The past rose up like bile, but Kazuo fought it back down. He would not worry that scab, healed over but still ruby bright. Was all of this only talk, or was there some deeper meaning he needed to read between the lines of what the man had said? He must have missed something. He read and reread his call log and as best he could replayed the conversation in his head. There had been, of course, the odd focus on death. Had the man been threatening him? Or perhaps it had to do with his job—perhaps the man was threatening Kazuo in his capacity as a JAL employee. Or the man could have been warning him, anonymously, of a threat to his person, to the JAL company, or to its passengers. Kazuo recalled the feeling of camaraderie. He had inherently trusted the voice, sensed—or perhaps assumed, he allowed—that on this night, like him, the caller was feeling lonely.

But what could the voice have been warning him about? Kazuo hadn’t a clue. He retrieved JAL’s thick binder on office protocol, flipped through it so quickly he cut his right index finger on the paper. He pressed a paper towel to his finger so he wouldn’t bleed onto office procedures. The blood flow staunched, he flipped until he found the checklist on airport threats. He skimmed the page: obtain precise wording of the threat; force caller to lose control so as to gather more information; be sure to note any background noises, which might help in identifying the location or identity of the caller.

The manual didn’t help much. He’d already decided the caller not only meant him no harm but, in fact, was trying to prevent him (or the airline) from coming to harm. One had to go with one’s gut on matters like this. With lives up in the air like this. Kazuo retraced the conversation again. But there was no wording of a threat, precise or otherwise, just this vague sense of dread that crept into him and lingered, right there next to the camaraderie. He hadn’t managed to force the caller to lose control or provide more information. He didn’t recall any particular background noises, either.

What did he know? Start there. He grabbed the call log and began a new entry. He left the “call received by,” “telephone #,” and “date/time” fields blank, and on the subject line wrote: More details regarding the “fugu caller.” In the memo section, he scrawled whatever came to him, as fast as they flew to him:

Not a wrong number. Caller identified employee by name. Employee unable to ascertain age from caller’s voice, except that he’s gone through puberty. Caller did not seem to be “under the influence.” No particular accent noted. Employee believes caller to be American born from his speech patterns and aforementioned lack of accent.

In his haste, his handwriting was tightly scrawled, all points and nooses. He should have detailed that first call. Instead, he’d written it off as a joke.

Caller is vaguely threatening or warning of a threat. Very insistent and specific about death by pufferfish. Possible threat to catering, or involving catering, based on the singular focus on death via ingestion?

The more he thought about it, the more it made horrible sense. Tetrodotoxin. Colorless and tasteless and therefore undetectable until it was too late. There was a weak sort of irony, too, in the fact that passengers were always complaining about how airline food was so bad.

Possible toxin: tetrodotoxin, from pufferfish. Could be easily mistaken for another pale pink fish until the fish is placed in the mouth. By which point it is too late anyway.

But why would someone want to poison the passengers?

The phone rang. Kazuo tensed but then snatched up the receiver. “Hold please,” he said in his most clipped and business-like tone. Without waiting for a reply, he placed the caller on hold. This was exactly what he’d been waiting for. He needed more intel. He scrawled quickly, finishing his train of thought and preparing himself to handle this.

Possible threat to airport, specifics yet unknown. Employee uncertain as to how to proceed.

But the hold light went from red to clear and the beeping stopped. The silence was very loud, because it ached with the inevitable ring that would follow. Indeed, seconds later, it began again. He picked up the phone and said, “I’m glad you called back. It was rather rude of you to hang up on me earlier. I was so enjoying our talk. I thought we were really getting through to each other, but then you disconnected.”

“ … hello?” said the voice.

“Sorry, sir, but you need to call this number instead.” Kazuo gave the caller a different phone number and hung up. He was in control now. He would drag the information out of the man. He would take copious notes. He would keep everyone safe. Kazuo carried the call log and pen to the other desk, where the second phone was, and waited. Predictably, moments later, it rang.

He picked up the phone, calmly answered, “Hai. Japan Air Flight Operations.”

“Hello? Hellooo?” said the voice. “Are you there? I can’t hear you.”

“I am here,” said Kazuo. “Just as I was earlier.”

The caller sounded indignant: “You again? Weren’t you the fellow that just transferred me? What was the point of that?”

“I cannot accept threats on that other line,” he replied. “Japan Air company protocol.”

“Are you—you’re not kidding, are you? You’re serious! You’re killing me here. HAA!” the man laughed. It was a rough sound, a laugh that tore free from the man’s gut, short and abrupt, perhaps involuntary. Like a dog barking.

He continued his notes in the memo of the call log:

Caller increasingly agitated. Regarding caller’s location: Employee still trying to ascertain.

Right then, it struck him. The caller had called him. Could it be so simple? Nobody outside of JAL or affiliate contractor employees would have this number. He brightened at the simplicity, until he remembered that these employees could be in San Francisco—as well as Japan, Brazil, Los Angeles, New York, and the rest of the airports at which JAL had stations. Still. He had narrowed the caller’s identity down from the impossible breadth of anyone in the entire world to something a bit more manageable. Quickly, he scrawled:

Probable JAL or affiliated contractor employee

Kazuo kept his tone flat and his breathing even. “Sorry, sir. You were talking so fast. Go slower. Why do you say I am killing you?” he paused and then went for the jugular. There was no time to waste. “When isn’t it true that actually you are trying to kill me? Or passengers? Or at least warn me of such a threat?” Kazuo paused pressed his ear close to the phone.

“Ha! HA! What are you, a comedian? Threats? Killing you? Jeezus, who is this, anyway?” The voice was having trouble stopping laughing. “Who put you up to this? Put Kazuo on the phone already. Let the poor man do his job.”

He was indignant. “This is Kazuo. The same person you’ve been talking to all night. About fugu.”

“About fu … what?”

“Fugu. Listen. Stop messing around. I want to know, right now, what I am dealing with. Is it poison? In the food? Who do you work for? Catering? Are you the threat, or is someone else?”

“Say, Kazuo, are you all right? Is that really you?” The voice was sobered, the laughter completely gone. “It’s Bobby. Bobby J. From maintenance? What’s going on over there?”

“Oh.” Kazuo smacked his forehead. “Oh, hey, Bobby. Sorry. Thought you were someone else. Sorry about that. Ha!” His laugh sounded hollow, even to him. “What can I do for you?”

“The usual,” said Bobby J. “Jeez, Kaz. You kinda had me scared there for a minute. Thought you went postal or something.”

As Kazuo updated Bobby about the estimated arrival time of the inbound flight and the approximate outbound fuel load, he kept the chatter breezy and bright. He laughed at the man’s jokes and asked after his wife and infant daughter. After they hung up, Kazuo lay his head down on his folded arms and hoped Bobby J. would not report his strange behavior.

Did it even happen? There was his call log proving he had taken notes, but no other evidence. The specter of white fish haunted him, his manhood crumpled in a napkin back in Sumida city. Here then was the irony, here the poetic justice—pufferfish had not killed Kazuo but, rather, some potentiality in him. He had always suspected his life was over at seventeen—now he knew it was true.

V.

The torafugu was in his mouth. It was slippery-smooth—tsuru-tsuru, Kazuo recalled the term—so fresh it seemed to be swimming around of its own accord, milling about amongst pearly rice grains. Expect a resilient chewiness, he thought as he closed his jaws onto the flesh. Open, close, open. Not exactly slippery—kind of slimy, but the rice was familiarly comforting. The taste will be as subtle as the fragrance of spring rain, as pristine as the water flowing over a river stone flanked by a virgin forest. Close, open, throat tickle. Long pause, but grandfather was looking at him. So, close, open, swallow. The bite of fish was still largely whole when it went down his throat. It stung as it went. Stray rice grains required a second swallow. And even then, the stubborn fish tried to swim back up, like a stupid salmon with the urge to spawn.

“So…? What do you think?”

His grandfather’s chopsticks were frozen, forgotten, mid-flight between plate and mouth. Glee lit his face. Kazuo reached for his water, changed his mind, then clasped his cup of sake instead, taking a large sip. Everything he had read was coursing through his brain. Where was the pure, clean flavor? How had he missed the umami, that mythical deliciousness, the holy grail of flavor?

“Absolutely shiko-shiko in the mouth,” pronounced Kazuo, reading straight from the memorized literature. He touched left forefinger to thumb and punctuated the statement with a short, firm shake. He was feeling better about the whole thing. That first bite hadn’t been so bad—tasted like a mouthful of seawater. Kind of like eating day-old squid, rubbery—even, he ventured, a little boring. This was what the Emperor pined for? Someone should tell him he wasn’t missing much. The texture had been a little tough on him, much chewier than its delicate appearance suggested. But he’d swallowed, and anyway, this was what he’d come here to do. To boldly swallow, and begin again, and find the man inside himself he knew he could be, far from the measuring stick of his father.

“Good, Kazuo, good.” Masa, briefly embarrassed by the thickness of his voice, placed the fugu-sashi in his mouth, letting the fish rest there till he couldn’t wait any longer and closed his teeth on it. He tasted deep ocean, the rush of the hunt, the fish’s sleek and hurried evasion of the fisherman, the moment that the animal realized it couldn’t outrun the boat—Masa savored the decision to fight. The flavor ballooned in his mouth, he could nearly feel the thrilling prick of the animal’s spines. He swallowed slowly, imagining that every surface of his mouth was lit up differently, and when he opened his eyes the room seemed brighter. The colors of the food on the table were more distinct. He felt more alive, full of hope. Masayoshi reached for his sake, swigged the rest in his cup despite what he’d told Kazuo about savoring it, and poured himself another to the brim, though customarily he would have waited for someone else to fill it. “Eat, eat!” he prompted, gesturing to the table, uncaring even of the high note his voice hit.

Kazuo picked up his chopsticks and selected a few pieces from the assembled plates. He had this now. Grandfather wasn’t even watching him. They were just two men, enjoying their meal. He fairly smirked as he lifted a large pink-white morsel, lightly grilled, to his mouth. But this piece burned when it touched his tongue. He shifted it about, debating how rude it would be to sip his water with his mouth full, then finally just bit down. The piece burst and hot liquid filled his mouth. With each nanosecond that the liquid sloshed around, Kazuo’s pulse quickened through his veins. There was a distinct tingling in his lips, a fat numbness to his tongue. Sweat broke out along his hairline, and in other unseen places, beneath his arms, at the small of his back, inside his underwear. Then his body rebelled, expelling the fish with force into the napkin he barely held to his mouth in time. He could not look at his grandfather. He rushed to the bathroom with his eyes down, not wanting to know if the restaurant was still empty or had filled with customers who were now staring at him. Mocking him. He locked himself into a stall, his gag reflex prompt and his body heaving. He sat there for ten whole minutes waiting for his grandfather, who never came.

Eventually Kazuo realized Grandpa Masa wasn’t going to come, so he flushed the toilet, unlocked the stall, and rinsed his mouth thoroughly at the sink. On the way out, he threw his napkin into the trash. He made his way through the restaurant, which had filled somewhat more, back to where his grandfather was eating without him. No one stared at him as he walked back to their private dining room—heads were bowed to the quiet, intent task of eating. All he could hear was full-volume, surround-sound chewing, sometimes a few boisterous slurps of soup. His grandfather’s plate was a mess of rice, fugu, and skin. Grandpa Masa did not acknowledge Kazuo as he continued to chew the bite in his mouth. Kazuo cupped his hands around his water glass and busied himself with drinking.

Once he had swallowed, Masayoshi raised his eyes to Kazuo. “You all right?” he asked gruffly.

At first, Kazuo nodded, not trusting his voice. But he had to know. “What was that?” he pointed to the large white morsel with the faint grill marks on it.

“Mmm. Shira-ko. A most prized delicacy.” Masayoshi concentrated on keeping his tone even. “You see, the fish spawn in early spring, so it is only available for a very short window of time.” He was finding it difficult to even look at the boy. “Like Beaujolais, or autumn Alban truffles.” He knew the boy didn’t know what he was talking about and he pressed on, not giving a damn. “Shira-ko means ‘white babies.’” He paused, then said with relish, “Grilled sperm sac.”

At this, the boy began drinking at his water again, in earnest. The girl came back to refill it. Masa grasped her wrist and took the water pitcher from her, setting it down firmly in front of Kazuo before releasing her. When she hovered, uncertain, Masayoshi dismissed her with an impatient flick of his wrist toward the door. “Nevermind. It’s an acquired taste. Have some more fugu-sashi. Or nigiri.” But the boy seemed to pale before his eyes, his posture slumping girlishly, so with aching disappointment Masayoshi relented. “Or sushi. Look, spicy tuna rolls. And here, some nice tuna-avocado-tobiko rolls. Your favorite.” Masa rearranged the plates. When he’d finished, it was like a line had been drawn, bisecting the table.

Kazuo helped himself to rice and those more familiar fishes that had materialized in his absence. They let the sounds of their chewing carry the silence between them. Their eyes did not meet. After they had finished eating, their waiter cleared the table and brought them cups and a pot of tea. Kazuo and Masayoshi sat sipping, cupping the warmth of the teacups. Grandpa Masa opened his mouth, then closed it, as if reconsidering. Finally, he said without malice: “I don’t understand it. Neither your father nor you is anything like me.” He could not have devastated Kazuo more. Kazuo felt the bile rise again, but he kept his face blank and concentrated on calming his stomach. His grandfather returned to sipping his tea.

About this time, there was a lull in kitchen orders, and so the owner-cum-head chef came out of the kitchen and made an appearance in their little private dining room. The chef exclaimed, “Ehhhh?! Ikeda-san! Ohisashiburidesu!” Grandpa Masa exclaimed back “Hai! Ohisashiburidesu, Namba-san! Kono aida wa, arigato gozaimashita!” Kazuo mouthed the words to himself with small lips, zeroing in on the ones he knew: Ikeda-san was his grandfather. Namba-san was the chef. Arigato gonzaimashita was thank you very much. Meanwhile, the two men exchanged very deep bows to show their very deep respect for each other and continued to fire back and forth rapidly in Japanese, most of which Kazuo couldn’t follow—save the words “chō-oishii,” very delicious, “shinsetsu na,” you are too kind, and “pichi-pichi.”

Then there was some sort of exchange regarding Kazuo, because he heard his name get passed through both men’s throats and saw his grandfather incline his head at him, unsmiling. The chef smiled tentatively and released a few short sentences at him. Kazuo opened his mouth to reply, but his grandfather interrupted dismissively, “nihongo hanashimasen.” Chef nodded at Grandpa Masa, then said in English: “I am saying to Ikeda-san, your ojīsan, that I am … hoping you enjoy the meal? The food is okay? You are not … sick?”

In response, Kazuo bowed so low he could see under the table. He wished he could crawl there and stay. “Uhm. … Hai. Chō-oishii, des. Very tasty.”

The chef inclined his head to Kazuo. “Ahhh, thank you, thank you, Kazuo-chan.”

Masayoshi thanked the chef once more: “Dōmo arigatō gozaimasu, Namba-san. You have outdone yourself. I will return, again, with great pleasure. You are a master. The fugu was perfect, just as I remembered it. Next time, though, perhaps I will bring a more appreciative companion?” Kazuo’s grandfather and the chef both laughed, again bowing deeply to each other. The chef went back to the kitchen.

When Masayoshi next spoke to Kazuo, it was to talk of their plans to explore Tokyo during the next week. They never spoke of the fugu again. Instead, they went through all the motions, riding the shinkansen, frequenting the ramen shops, marveling at the flashy, plugged-in wonder of Akihabara, gawking at the gothed-out lolitas of Harajuku, burning their prayers at the Meiji-Jingū shrine, getting lost in the Escher-like half-floors of Tōkyū Hands and puzzling over its clocks that tick backward, partaking in the bustle of the famous Tsukiji fish market. They did all of these things together, but the distance between Kazuo and Masayoshi only grew more pronounced.

Back on board for the long ride home, Masayoshi let the steward stow his bags and moved into seat 1A, pointing his finger across the plane to 1K. He’d paid extra for these seats in first class, where he and Kazuo could each have their own window and were separated by aisle, seat, and another aisle. At cruising altitude, he could lay the seat flat into a bed and knock out till they were back in the States. For now, though, he propped a pillow against the window, ignoring even the steward’s polite offer of a drink, feigning sleep. And what was there to feign? He was an old man—old enough to have a grandson who, at seventeen, had a long life ahead of him, and although that way couldn’t be charted, Masa, for one, could see the precautionary nature it would take. Without opening his eyes, he reached furtively under his blanket and undid his seatbelt. He recognized this for the childish gesture that it was, but for no clear reason it comforted him. Soon he was no longer feigning sleep.

Kazuo stowed his things and when prompted, asked the male flight attendant for a cranberry juice. Across the aisle, Grandpa Masa was already asleep. It was mid-day, but maybe sleep was the way to go—some seasoned traveler’s secret to avoiding jetlag. Or perhaps his grandfather was genuinely exhausted from all the walking they’d been doing. Kazuo knew he could come up with a million reasons but none would ring as true as Grandpa Masa just being tired of him. Maybe he was still a “boy,” but he wasn’t stupid.

In the years that would follow, Kazuo no longer let himself imagine what his life would have been like as a pilot. He finished high school, graduated, took a job under his father, working the ramps for Japan Air Lines. Found he liked it. Found he had a real skill for rote memorization. Computer codes. Three-letter airport abbreviations. Formulas for weight and balance. Endless acronyms. NOTAM, Notice to Air Men. GMT, Greenwich Meridian Time. And after 9/11, TSA and Code Orange. It was a vernacular, and Kazuo became fluent with ease. He worked his way up from there, memorizing, training, testing, and landing finally at the position of Flight Operations Officer. He spent his days plotting the routes of JAL’s flights as they soared through the sublime, bypassing cold fronts, maneuvering around typhoons, and minimizing turbulence. It had taken so much to get to where he was. He comforted himself with the order of things. He could tell you that the presence of altocumulus on a humid day meant an advancing cold front and thunderstorms on the next. He could create macros within an Excel template to pinpoint the exact amount of time a plane would be delayed by mechanical or human error. And he could imagine few finer pleasures than unfurling the high-altitude enroute charts, full of their coordinates and route names, an elaborate roadmap of the sky. Kazuo saw it in three dimensions, the waypoints knotting together various airways like constellations.

But for now, Kazuo was still the boy in the hulk of a triple-seven. He glanced again across the plane, but his grandfather either slept or pretended to. He raised the window shade and saw nothing, but he knew of the flurry of men below. They had cleaned the interior, exchanged the food, emptied the lavatories, calculated the distance and difficulty of the flight, and appropriately fueled the plane. They were calculating the load, puzzling where each piece had to go. They were researching weather advisories, spreading out flight maps, briefing pilots, conferring with ATC. They were going over TSA passenger lists highlighted for terrorists. They were hauling containers of mail, private shipping pallets, and hundreds of overstuffed suitcases. The dogs, cats, and exotic animals would soon be stowed and the air-pressure and conditions of that cargo hold carefully checked.

Nowadays they had up to three men in a cockpit, and for what? Kazuo remembered what his father once told him—that after 9/11, computers had become the brains of the flight industry’s operations. Pilots were there to chaperone and to provide a reassuring human face to the cockpit while flying through such suspicious skies. “The aircraft can—for all intents and purposes—fly itself,” said Tadao. “Pilots press a few buttons to take off, another few to land, and don’t do much else in the meantime.” He and the rest of the men on the ground were actually more essential than pilots. At the time, Kazuo dismissed his father’s comment, couldn’t hear him through his firmly held, romantic view of pilots as real men, but as he watched the forward compartment being loaded, he knew it to be true. It was his father who held the plane in his hands.

Art by Kerri Augenstein

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#372a55′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

[av_one_half first]

[/av_one_half]

Mayumi Shimose Poe is a freelance editor and writer. Recent work has appeared in Bamboo Ridge, Drunken Boat/Anomaly, Frontier Psychiatrist, Hawaii Women’s Journal, Hybolics, and Japan Subculture Research Center.

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#372a55′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]Sport media | Cactus Plant Flea Market x Nike Go Flea Collection Unveils “Japan Made” Season 4