[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#1f4378′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

It was a frigid New England February day, much like this one, when we were first introduced. Of course, I imagined that I knew something about you beforehand, by the way you moved and kicked and somersaulted in my belly — by your satisfied silences and painful protests. The only ‘real information’ I had was that you appeared to be healthy, and that you were a girl.

I prepared your sister and our home for your advent: Another crib with attractive floral bedding, matching dresses, spring bonnets in duplicate and coordinating bathing suits for the summer. Your dad protested all this unnecessary expenditure, but I slyly reasoned that birthdays a half year apart meant that hand-me-downs would be seasonably unsuited. And so I dreamed, and I clicked, and adorable and trendy confections in pink and purple and mint and magenta arrived at our doorstep. It was folly but it was fun.

When we finally met you were momentarily silent. You took a pause to adjust to your surroundings before announcing your presence as I anxiously strained the only autonomously movable part of my body, my neck, to catch a glimpse of you around the blue curtain where the surgeon had extracted you from my womb. The surgery had been painful, the anesthetic insufficient, but all that was forgotten as every fiber of my being was focused on your unseeable presence. And then I heard you. You didn’t whimper, you didn’t cry, you didn’t squall. You ROARED: “Here I am!” Soon after, as you lay swaddled near my head in a white towel with pink and blue stripes, I was able to gaze into your eyes through a happy haze and introduce myself in return.

“Hello Princess,” I said, “I’m your Mama.”

Your dad often recounts the moment he held you first. Your hearty, solid body, your pumping fists and legs and the surprised thought, “This one is a different model,”comparing you to your dainty sister. In the weeks after, we would share all the funny and not so funny moments with our friends: the attempted VBAC, the insuing complications and that hilarious moment when the anesthesiologist, from her poor vantage point at the head of the gurney called out, “It’s a boy!” Hilarious, because you were not, most definitely not, a boy.

What you most definitely were was a spirited little thing. As you grew, you had a way of fearlessly barreling around and into things that earned you the nickname “honey badger.” For mild plagiocephaly (flat head), you wore a bright pink football helmet for several months before your first birthday. We assigned your audacity to the fact that the helmet protected you from the consequences of most of your escapades.

You had a curiously deep voice and a blithely cheerful personality. As our second child, you benefited from the benign inattention of more relaxed parenting. However, despite its charms, your ‘knock about-edness’ began to concern us as time went on. You lacked coordination, constantly falling off and into things, sometimes seeming to deliberately throw yourself into the couch or floor. We contacted our local Early Intervention specialists and after a lengthy assessment you received services for Sensory Perception Disorder, a minor hiccup in an otherwise pristine medical record.

When your baby sister came along you were still in diapers. You welcomed her with generosity, with no significant jealousy or displacement. You three were so close, so affectionate to each other. Our family was complete. Three healthy, bright, beautiful girls: we had spun the wheel of fortune and won the jackpot. There were no clouds on the horizon and the sun shone in perpetuity. Of course I exaggerate. There were tussles and tiffs, bumps and bruises, reflux and influenza, terrible twos and tormentuous threes. But for the most part, I was grateful beyond measure that our lives were so lovely, so ordinarily good. I enjoyed posting pictures of my darling daughters, now dressed in triplicate, to Facebook, and I reveled in the compliments we received.

As you crested the middle of your second year you developed a curious habit, a persistent routine. You started to change your clothes repeatedly, maybe 10–12 times throughout the day. I reacted with both annoyance and mounting concern. Your pile of sartorial rejects meant exponentially more laundry. Goodbye matching dresses. My concern was that your habit was tinged with compulsion. When you woke up crying at 2am one night begging to be allowed to change into a new outfit, I called your pediatrician. Since you did not display other signs of compulsiveness we associated your desire to change with your general sensory seeking behavior. You were changing clothes in order to feel the fabrics rub against your skin. Children with a sensory deficit often seek sensations because they do not experience them to the full extent that the rest of us do in the ordinary course of our day.

This theory held water for only so long, for soon after you started preschool at 2.9 years, you became attached to one particular garment — a short-sleeved cornflower blue turtleneck sweater with a brown dog on the front which you wore for the next six months with few exceptions. You wore your ‘doggy sweater,’ day and sometimes, if you won the battle, night. You wore it over your tutu to ballet class, and over your holiday dress to see Santa at the mall. I ordered several more on eBay. Again, I cursed silently as I increased the frequency of my laundry to accommodate your needs. Since the weather was chilly we had a temporary reprieve from having to figure out how the doggy sweater would work on top of swimwear. I decided to fight that battle come spring. But by the time spring arrived our struggles over the doggy sweater would seem trivial compared to something new and far more alarming.

In the interim between the advent of the doggy sweater and your third birthday you set a stake in the ground and declared yourself a boy. At first we bantered with the word “pretend.” We explained, and you acknowledged, that you were pretending to be a boy. At preschool you tentatively assigned yourself to the male faction of the class and you were told that you were pretending, and that pretending was fine as long as it didn’t interfere with the workings of the school day. When I was told that you were told that you were pretending, I nodded and acquiesced. It made sense. This new thing was foreign and it was troublesome and above all, it seemed unhealthy. Another obsession. Another whim.

Whim or not, our home soon became a battleground over gender with you constantly pulling me, your dad and your older sister into unwilling skirmishes. You would glare at us with your huge defiant brown eyes and say, “I AM A BOY,” and I, a great believer in the principle of the inverse proportionality of parental disapproval to a child’s sedition gave little protest. I would sigh: “That’s fine sweetheart. You can be what you want to be in our home.”

I kept your sister off your back when she protested your apparent disregard for basic biology (which we explained to you). We started to have discussions about the narrow-mindedness of gender expectations: pink and blue, dolls and trains. We assumed that you were stating a preference for things un-girly. We couldn’t comprehend that you could even conceive of what gender was when you had barely begun preschool. So we told you to go ahead and wear boy clothes, and that gray was a perfectly acceptable favorite color for a three year old girl, and that yes, if it was important to you, we would call you Jackson, or Max or Jake or whatever the nom du jour was.

You never asked us to call you anything but Mia, your birth name, in the public arena. But our soothing acceptance never seemed to be enough. You became watchful and guarded at school and in public. At home, there were many occasions that you let go, hitting, kicking and punching, wailing and screaming: “Don’t talk to me!” “Get away from me,” and frequently, “You ruin everything!” Your anger seemed atypical, in excess of the ordinary emotional vicissitudes of being three.

You had always been jolly and loving as an infant but now I was the only one you would kiss and hug — you frequently exploded if anyone else tried to show you affection. Sometimes, even with me, if I casually brushed your hair with my hand or gave you an unsolicited hug you would recoil and bark angrily at me. And that was another thing — your new, quite unsociable habit of pretending you were a dog when people addressed you. You would lope around in a circle, as if chasing an invisible tail, tongue hanging out, “Aarf! Aarrrf!!” leaving us to explain your odd behaviors. To be fair, we had many peaceful moments and it wasn’t all bad. Sometimes you relaxed and your beautiful happy nature shone through. Those moments were a blessing, a dream — and I cherished every one, bracing for the next upset.

I knew that being ‘as a boy’ was important to you. I knew little of the word “transsexual.” I had first encountered it as a young adult, riveted to the dark thriller Silence of the Lambs, in which the antagonist, “Buffalo Bill,” skinned his victims in order to create for himself a ‘woman’ body suit. I was aware that there was a newer term — transgender — and that, in my way of thinking at the time, younger people could be ‘afflicted’ with this too. It was weird, it was beyond the pale, it was, to my current shame, slightly grotesque. I did not truly believe that it applied to my beautiful, round-faced, bright-eyed, innocent preschooler.

But then one day in the late fall of your third year I attended a routine parent teacher conference. Your teacher expressed her concern in hesitant tones: “You know, Mrs. Lemay, has it ever occurred to you, is it possible — that Mia may actually believe she is a boy?” You had just learned how to write your name, all jumbled letters and fat precious pen strokes. We were so proud of you. You however, did not share our pride. Apparently, when required to write your name you would comply, but then immediately cross it out. This obliteration of the marker of your given identity spoke volumes about how you perceived or rather, refused to perceive yourself.

Reality, which had been hovering just out of conscious reach, struck. My stomach churned. I tasted the ash in my mouth (I never understood that expression before). Tears stung as they welled up in my eyes. I tried to stem the flow out of embarrassment, wiping my eyes and nose on my sleeve, standing in the middle of the bare auditorium, no box of tissues in sight. Not my little girl. Not happening. Please wake up.

I stumbled through the next days in a painful haze. We were a few weeks shy of winter break and I reached out to a friend of ours, a therapist who had worked with at-risk LGBTQ youth. As we stood doling out cheddar cheese bunnies and pretzels to our raucous offspring on a play date she confirmed my fears — we should consider that you might be transgender.

I pressed her to tell me what that meant. Not the dictionary definition, but what the implications were: to your future, to your physical and mental well-being and to our family. I heard words like “outcomes” and “high-risk” and “medical intervention” and statistics like “over 40% attempted suicide,” and my world started to unravel. She tried to temper these dark things with words of encouragement and moral support, however it was impossible to process any further. The blood was rushing too strongly in my head as my heart was being carried downstream with the vestiges of my fantasy of a wonderful life for you.

I freely write about the negative emotions that the possibility of your transgender nature evoked with regret, but no shame. By now, you know how proud I am of you, how happy I am to be your mother, and how I perceive your unique nature as a precious if puzzling gift. At the time though, it was a devastating blow.

I began to grieve, waking up in the early morning hours biting my pillow to silence the sobs, my sheets bathed in the stink of bad dreams. I was losing you, my precious daughter. You were in the room next to me in peaceful childhood slumber, but you were most assuredly slipping from my grasp, hurtling into a void of social rejection, physical mutilation and suicidal depression. I felt helpless. I began, as many parents do when faced with a child that has unique needs, to ask, “What is the treatment?” by which I meant: What is the cure.

I called the Gender Management Clinic at Boston Children’s Hospital, and although you were too young for the program they referred me to a therapist who had experience with transgender youth. She was not covered by our insurance at the time but was willing to speak with me at length on the phone. She advised me that many children — up to 70–80%, who present as gender-non-conforming (running the gamut from tomboy/effeminate to truly transgender) revert to their assigned, or ‘born’ gender upon reaching puberty. Oh phew. What a relief. “Keep things fluid,” she further advised, “Try not to box your daughter into making a choice either way. Just show support.” All good advice and I was temporarily buoyed by the hopeful news. To my desperately seeking ears, this meant you might well be going through a phase. How wonderful.

And so we left things. You asked to cut your hair and we gave you a sweet pixie cut. Keep it fluid. It was all about compromise those days. Slowing your inexorable march toward all things boy. For your dance recital, your instructor graciously allowed you to wear a tux with a bright pink bow-tie and cummerbund to match the sequined tutus your classmates wore. Your wardrobe was by this time mostly boy clothes. I say mostly, because I snuck in girl clothes in dark colors…they had tiny embellishments, embroidered hearts and bows that reminded me that one day, you could be my little girl again. In my eyes, they also served to ward off the questions I imagined I would have to answer about your appearance to those who knew you as a girl.

For a while you tolerated this deceit, but you soon became quite canny at the subtleties of gendered clothing. You would reject the white Peter Pan collar in favor of the crisp button-down. A-line shirts and ruched sleeves disappeared from your drawers, along with velour and Lycra. Hanukkah and Christmas came and went and you received superhero action figures and matchbox cars from us and your wonderfully perceptive Grammy and purple pajamas and pink pencil sets from well-meaning loved ones who didn’t understand the extent of your preferences. You jumped for joy with the one and wrathfully rejected the other. Even I still clung to the belief that if you could only see the gray areas between the pink and blue you might find yourself at home somewhere in between. Hence the Katniss Everdeen doll that made its way into your heap of Christmas loot. I still recall your look of utter disdain.

It was soon February again and we celebrated your fourth birthday. And you grew taller, wiser and accomplished many things. Over the winter break I had tentatively broached the topic: Would you be happier with a boyish/unisex name at school? You categorically refused. Your answer gave me a covert thrill of hope. I dared to dream that you were not fully committed to being a boy, and that you would be one of the preponderance of kids who ‘figured it out’ because their parents didn’t make a huge deal out of it. For use at home, you settled with us on a name which sounded similar to your given name in order to avoid the confusion of the daily merry go round of arbitrary boy names. We urged you, and you accepted the name Mica.

It was your dad who came up with a brilliant scheme — when you went to school, you could add an apostrophe, a little sickle on top of the “I” in Mia that would stand in for a letter “C.” This would mean you were writing Mica, not Mia and therefore you needn’t cross it out. We all giggled at the subterfuge and it was enough, for a while.

But I knew in my mother’s heart that you were not truly happy. Not like your sisters. Not like the unburdened joy that I thought you ought to have felt coming from a warm loving home with plenty of affection, positive experiences and toys galore. There was an un-childlike, persistent sadness that lay about you like a pall in those years which should have been so magical.

You see, I believe that what had happened while I was wasting my energy hoping that you would make peace with your biology was that we had become unwitting contributors to your fracture into two different people: “Mica” and “Mia.” Home and school. Boy and girl. Unguarded and guarded. Open and shut. Reality (yours) and role-play (ours).

On the home front things were most certainly getting ‘better,’ or should I say, ‘easier?’ Your tantrums subsided as we managed to convince you that we were truly OK with you being a boy and that we believed that what you felt about your identity and your expression of it was your choice. Your sister had become a huge support in this regard. Not many five-year-olds could act with the grace and compassion that she did (and still does). She stopped teasing you about not being a ‘real boy’ and accepted our mantra that “what you are in your heart and your mind is far more important than what you are in your body.” The hard knot of your anger started to dissolve. We all basked in this momentary detente.

In the early spring of your fourth year we went on a glorious trip to Disney World where you were the only kid we saw in a Prince Charming costume. You glowed when strangers stopped and remarked, “Isn’t he adorable!!” and “What a handsome little man!” and we didn’t correct people, because we knew how much you enjoyed being ‘mistaken’ for a boy. The status quo was an OK place to be.

But back at school, activities and in our community at large you remained markedly withdrawn. Our reports from your teachers were that, if prompted, you joined in group activities. You rarely, if ever, engaged your peers in free play. The day you hugged your teacher for the first time brought her to tears. I believe you occupied a special place in her heart and that she felt protective of you. I am so grateful for the good people in our lives.

Despite the fact that you were beginning to relax in the classroom, you continued to erect walls between yourself and others. The barking and loping persisted, and always there was the hood that would come over your eyes that said: shutting down now. In my ignorance I even wondered at times whether you were touched by a mild form of autism, but it seemed incongruent that this behavior turned on and off as if by a switch.

It was that playdate at Papa Ginos that shuttled me right over the edge from keeping it fluid to the time is now. To be truthful there were many small fissures forming in the Theory of Status Quo as I have now come to see it. There was your tearful sister begging me to force you into a dress so that “people will treat her nicer.” There was the sweet little girl at a birthday party that asked me about you: “What is that? Is that a BOY or is that a GIRL?” There were the burgeoning signs of dysphoria (“What’s wrong with my body? Why did God make me like this? Is he stupid?”).

But what finally broke me from my unhappy trance was nothing more complicated than a post-last day of school pizza party where I got a chance to see you interact with your classmates outside of a structured setting. Everyone was there, the boys, the girls, and most of the moms. You sat down at the edge of a gaggle of girls and tucked into your slice. No one jostled you in friendly banter, no one yelled, “Come on Mia! Let’s run to the end of the restaurant and back!” The happy little bodies were in constant locomotion, stepping around you and over you as you sat staring at your pizza. Then you looked up at a group of boys being disciplined by their frustrated moms for running amok, “Sit down Jack! Behave Grady!” and the expression on your face skewered me. It was a hunger that I had never seen before. You weren’t confused. You knew where you belonged. You just didn’t know how to get there. What if it was I who was responsible for showing you the way?

School was officially out for the year. You were signed up for the next year. Another year, deposit down, of living two lives. Open-shut, boy-girl. I watched you carefully during the next week while you enjoyed a camp run at your preschool, and I thought and I weighed, and I deliberated and I doubted until a million possible futures nearly drove me to distraction. What if? Your dad and I talked long into the evenings after you had gone to bed and in the mornings before we emerged from ours. A video had gone viral in the weeks before. A slideshow of a transgender boy, not much older than you, whose loving California family had supported his public transition. We wondered if seeing the pictures of this boy who was so obviously happy in his ‘new skin’ could make you believe in the possibility of your own fulfillment.

It was Friday, June 13, in the evening after your last day of preschool camp when we called you upstairs into your Dad’s office. We told you we had something for you to see and so you sat, engulfed in your dad’s big black swivel chair as he cued the video on his laptop. I translated the words into ‘kidspeak’ as they began to flit across the screen, accompanied by wonderful, endearing pictures. You viewed intently and solemnly as young Ryland Whittington was transformed from a beautiful little girl with golden locks into a handsome smiling boy in a buzz-cut and tuxedo. When the video ended you asked to watch it again. Then you sat staring at your hands. We asked you what you thought about the boy and you shrugged, stone-faced. The walls you had erected were made of hardier stuff than we expected. But the moment was now. All three of us in this room, your palpable pain, the resolution we needed to help you find.

So I got down on my knees and took your soft, still baby-like little hands in mine. I asked you to look at me but when you lifted your beautiful gaze to mine, I was momentarily speechless. I rallied: “I believe you,” I said and I didn’t bother to wipe the tears with my sleeve this time. “We believe you. All we want is for you to be happy, but you need to help us understand what will make you happy.” Your dad knelt down next to you too. “Do you want to be a boy all the time like that boy we showed you?” he asked gently. Your eyes filled immediately. “I can’t,” you responded with a quivering lip. “I HAVE to be Mia at school and Mica at home.”

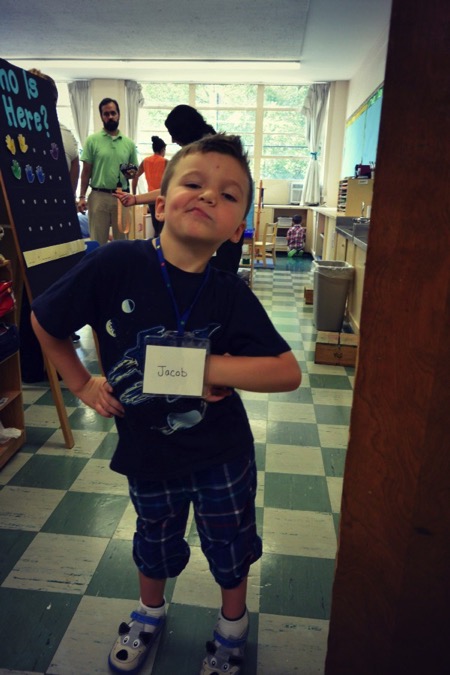

So we told you. We told you about the choices, any of which you could make — or not. We told you that these choices were yours. Among which, you could continue at your school as Mia. Or, you could go there next year with any new identity and finally, more radical yet, we could find you somewhere to start anew, to simply be the boy you had insisted for so long that you were. You paused a long while. I didn’t know if you could do it. I didn’t know if you had the faith in us to tell us what you truly wanted. I didn’t know if you could imagine a future where you were whole — one identity: body and mind. You broke the silence. “I want to go to a new school. I want to be a boy always. I want to be a boy named Jacob.”

Jacob, my love. It’s been nine months and change since that fateful Friday and so much has transpired to make us believe that the journey we are taking together is the one we need to be on. It’s been tough, make no mistake, and solving your more immediate identity crisis did not resolve all the latent feelings of shame and sadness that you have suffered. But the powerful effect of your transformation was almost immediately felt by all who knew you and loved you.

Within days of beginning life anew as Jacob you began to stand up straight and look people in the eye. You stopped barking like a dog and running for cover. In allowing your transition, we were only hoping to help your spirit survive. We did not expect the seismic shift in your personality that we experienced. You cracked your first real joke within a week, took a fresh interest in learning your alphabet (ironic since school was out) and so much more. You started to cuddle and kiss, laugh and sing —and the dam just broke. You talked and talked and talked as if someone had taken a muzzle off your mouth. You took up hobbies, collecting anything and everything you found that piqued your interest (mostly detritus: scraps, stones and screws you picked off the street to my chagrin). That summer, the world opened up its treasures to you.

Your dad and I were astounded, delighted and profoundly gratified. These positive experiences were crucial for us, because those early days were laden with fear. We were always double, triple, quadruple guessing our decisions, approaching each “re-introduction” with trepidation. It all seemed so fragile. We fretted: Who would break your trust? Who would clip your wings? Who would sneer or giggle or laugh, sending you running back for cover? But you were strong, not fragile. You were brave, not weak.

Together we weathered the firsts. The first time we wrote your name — yours, a triumphant experience, mine, accompanied by a floodgate of tears. The first time I asked someone to call you Jacob, and finally, the first time that you did. Your first Christmas acknowledged as a boy. You confessed afterward that you had half expected Santa would forget and bring you Mia’s presents. Oh baby. The first public announcement, followed by a deluge of love and support from beloved family and friends — their support carried us and continues to carry us. The first week of the new school (you were obsessed about the bathrooms for the longest time) and the first time we ran into someone from your old school (it was awkward, we survived).

Jacob, my love, it is you that have transitioned us to a life less ordinary, and so much more meaningful than it ever would have been. Thank you deeply for your sacred trust. The mystery that is you may never be amenable to a full resolution. I don’t know what’s beyond the next bend in the road but I am no longer afraid.

I believe in the goodness of people. And I believe in your ability to dispel much of the ignorance and intolerance in those you may encounter. I look at how fine a human being you are becoming— far beyond my meager original intentions — and I know that the future is bright for you. I am no longer afraid.

And it is because I no longer fear: the outcomes, the medical interventions, the bigotry, that I will not be filing this birthday letter in a box in our attic with those of earlier years. Rather, momentarily, I will set these words free — relinquishing my control over their trajectory and destination. Their intent is to provide comfort and strength to another mother or father with an aching heart. To provide the message: It doesn’t get better. It gets awesome.

For I have seen and wish to share remarkable things. In those early days as Jacob, I saw the most authentic parts, in the deepest reaches of you, begin to unfold. I saw you take your first huge breaths. I saw the clouds above your head scatter and run. At first there was a silence, as you paused to take in the new world around you, and then you roared: I AM HERE!! It was then that I realized that we had indeed met before, but that truly I had not recognized you that first time. It was then that my grief began to depart as I knew in my soul that you had always been my son, Jacob.

And so always, my love,

Mom

Art by Matt Monk

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#1f4378′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

[av_one_half first]

[/av_one_half]

Mimi Lemay is an international advocate for transgender youth. She and her family meet regularly with legislators, business leaders, educators, and clergy to share their vision of a more equitable world. She is a member of the Parents for Transgender Equality National Council at Human Rights Campaign and holds a master’s in law and diplomacy from the Fletcher School at Tufts University.

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#1f4378′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]latest Nike release | [169220C] Stone Island Shadow Project (The North Face Black Box) – Hamilton Brown, Egret