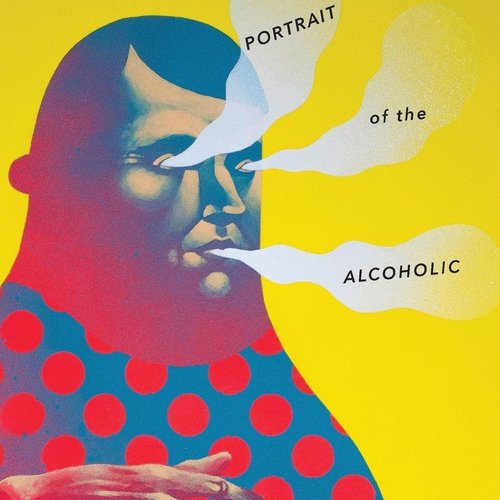

Portrait of the Alcoholic – Kaveh Akbar

Sibling Rivalry Press

2017

Kaveh Akbar in Portrait of the Alcoholic writes with such spiritual risk and honesty that we as readers are brought into the liminal spaces of language, addiction, and displacement. Sobriety is maintained through community, and empathy is written into every poem of this collection. These poems explore relationships between addict and drink, between people, cultures, and languages. From the opening poem, “Some Boys Aren’t Born They Bubble,” we are pulled in by Akbar’s wild metaphors and similes: “sometimes one will disappear into himself / like a ram charging a mirror when this happens / they all feel it.” When I ordered my copy of Portrait of the Alcoholic, I’d recently been released from probation for a DUI, was working fewer and fewer hours at the bar where I’d worked for nine years, and was easing into the realization that I had an unhealthy relationship with alcohol. At weekly, court-mandated AA meetings, I listened to people’s stories and contributed my own. We felt collective pride when someone maintained sobriety and collective worry when another relapsed. This sense of community and shared recovery comes through Akbar’s opening poem and is maintained throughout this gorgeous collection.

Empathy is central to Portrait of the Alcoholic, as are moments of profound vulnerability. “When I wake, I ask God to slide into my head quickly before I do,” Akbar writes in the poem “Being in this World Makes Me Feel like a Time Traveler.” When the court mandated I attend AA meetings, I feared being inundated with religious dogma. That wasn’t my experience. Attending a small meditation group Saturday afternoons, I was grounded by our discussions and weekly repetition of the Serenity Prayer. We talked about spiritual fitness. We practiced mindfulness. The disease of alcoholism is tricky — Akbar beautifully articulates its complexities and the necessity of vulnerability in maintaining sobriety.

It’s not only alcoholism that these poems grapple with, it’s also immigration, language, memory, displacement, and the realities of a life lived in the margins and with resilience. These themes are woven together seamlessly in the poem “Do You Speak Persian?” Akbar writes,

I don’t remember how to say home

in my first language, or lonely, or light.

I remember only

delam barat tang shodeh, I miss you,

and shab bekheir, goodnight.

How is school going, Kaveh-joon?

Delam barat tang shodeh.

Are you still drinking?

Shab bekheir.

For so long every step I’ve taken

has been from one tongue to another.

From his childhood in Iran to his life in the United States, Akbar has carried not only memory but also the loss of memory, not only language but also the loss of language.

Language is also a means for resistance, for gaining control over craving. Step one of Alcoholics Anonymous is to admit we were powerless over alcohol, that our lives had become unmanageable. By naming a thing, by admitting to the disease of alcoholism, there’s some power regained in an otherwise powerless situation. Akbar’s tone is tender even as it’s regretful. “I am less horrible than I could be,” he writes in the poem “Calling a Wolf a Wolf (Inpatient),”

I’ve never set a house on fire never thrown a first-born off a bridge still my whole life I answered every cry for help with a pour with a turning away I’ve given this coldness many names thinking if it had a name it would have a solution thinking if I called a wolf a wolf I might dull its fangs

Vulnerability is in this honest examination of self, an attempt to gain control of craving in its naming.

In the poem “Portrait of the Alcoholic with Craving,” Akbar writes in stanzas that zigzag across the page,

I’ve lost the unspendable coin I wore around

my neck that protected me from you, leaving it

bodyhot in the sheets of a tiny bed in Vermont. If you

could be anything in the world

you would. Just last week they found the glass eye

of a saint buried in a mountain. I don’t remember

which saint or what mountain, only

how they said the eye felt warm

in their palms. Do you like

your new home, tucked

away between brainfolds? To hold you

always seemed as unlikely

as catching the wind in an envelope. Now

you are loudest before bed, humming like a child

put in a corner. I don’t mind

much; I have never been a strong sleeper, and often

the tune is halfway lovely. Besides, if I ask you to leave

you won’t.

The poem continues this mindful attention to addiction, and is true to the experience of recovery. The addiction doesn’t go away. Here, Akbar addresses alcoholism as though it was a person, and this heightens the intimacy between alcoholic and alcoholism. We readers feel the persistence of craving, as we experience it through Akbar’s rich language and sensory detail.

As someone who has struggled in my own relationship with alcohol and alcoholics, I related to Akbar’s beautiful articulation of desperation and need, and of recovery. The willingness in these poems to express a raw vulnerability and to name an experience we often keep secret is as healing as it is artistically rewarding. Kaveh Akbar’s Portrait of the Alcoholic is a collection that sings of experience, that evokes vulnerability, and that implicitly asks us as readers to look honestly at our lives.

Kaveh Akbar’s poems appear recently or soon in The New Yorker, Poetry, Tin House, Ploughshares, FIELD, Georgia Review, PBS NewsHour, Harvard Review, American Poetry Review, Narrative, The Poetry Review, AGNI, New England Review, A Public Space, Prairie Schooner, Virginia Quarterly Review, Poetry International, Best New Poets 2016, Guernica, Boston Review, and elsewhere. His debut full-length collection, Calling a Wolf a Wolf, is forthcoming with Alice James Books in Fall 2017, and his chapbook, Portrait of the Alcoholic, is out with Sibling Rivalry Press. The recipient of a 2016 Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fellowship from the Poetry Foundation and the Lucille Medwick Memorial Award from the Poetry Society of America, Kaveh was born in Tehran, Iran, and currently lives and teaches in Florida.

Kaveh founded and edits Divedapper, a home for dialogues with the most vital voices in contemporary poetry. Previously, he ran The Quirk, a for-charity print literary journal. He has also served as Poetry Editor for BOOTH and Book Reviews Editor for the Southeast Review. Along with Gabrielle Calvocoressi, francine j. harris, and Jonathan Farmer, he starred on All Up in Your Ears, a monthly poetry podcast.Running sports | Nike SB Dunk High Hawaii , Where To Buy , CZ2232-300 , Worldarchitecturefestival