Shapeshifting is my ultimate obsession in storytelling. Because as we all know, change is unyielding and constant. It never sleeps. Shapeshifting stories allow this truth to manifest literally—so ultimately, transformation is ever-present in lore because it is ever-present in life.

Tag: poetry

For Folk’s Sake: In Brief with GennaRose Nethercott

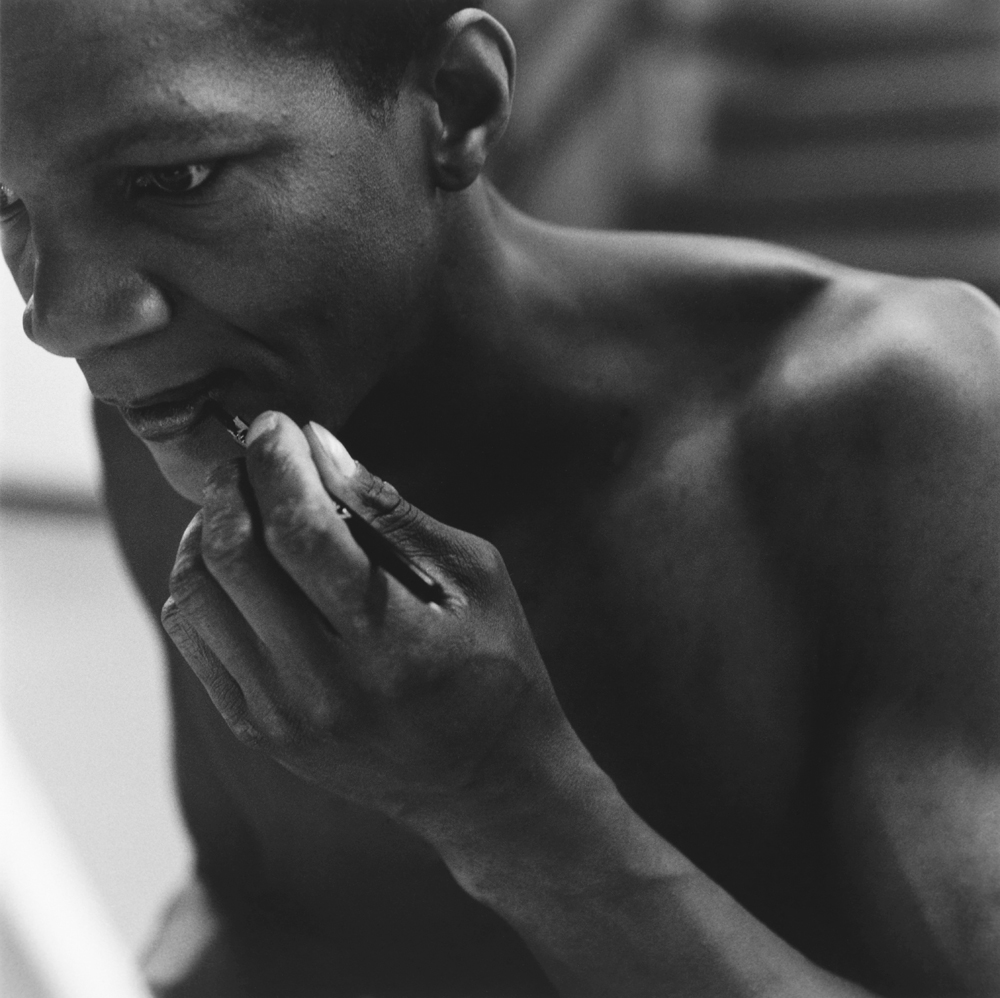

Ruben Quesada Talks Poetry, Translation, and Neck Tattoos

by Blake Z. Rong

On the right side of his neck, just below his ear, poet and professor Ruben Quesada has a tattoo of the Chinese character 晨, set within a thick black circle, which he tells me means, “early light.” Quesada was born on an early morning in a late summer day, in August in the 1970s. “I… Continue reading Ruben Quesada Talks Poetry, Translation, and Neck Tattoos

by Blake Z. Rong

Wonderland:

Readings by Matthew Dickman

“It seems like everyday now, anytime we make art, or really listen to someone else’s point of view, or empathize with the other, that it’s a fight against meanness…”

Silhouettes of a Vermont Poet at Home: An Interview with Kerrin McCadden

by Valentyn Smith

“Shifting between different forms, even ordering of the lines, helps expose what should be cut. I’m a poet who errs on the side of too many words, and it takes me tricking myself to see where I should lose any of them.”

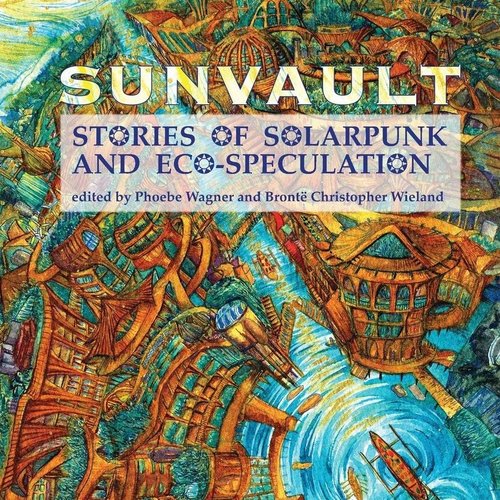

Book Review: Sunvault: Stories of Solarpunk and Eco-Speculation

by Paul Daniel Ash

The literary world has been applying the “-punk” suffix to science fiction sub-genres so frequently and for so long that it sometimes verges on self-parody. It all began with cyberpunk, a description of the 80s noir-esque SF of Bruce Sterling, Rudy Rucker, and of course William Gibson. This was soon followed by steampunk, a term… Continue reading Book Review: Sunvault: Stories of Solarpunk and Eco-Speculation

by Paul Daniel Ash

A Poetry Reading

from Tom Paine

3 Poems from Tom Paine

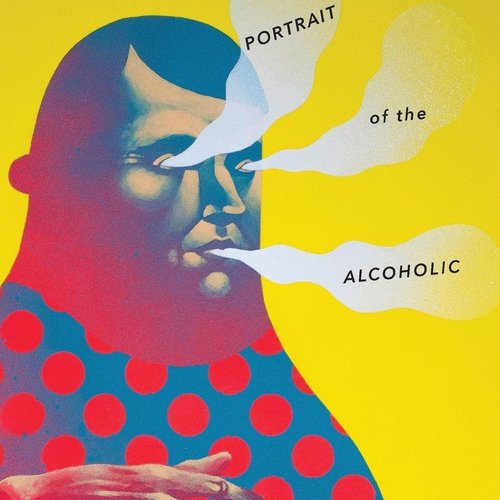

Portrait of the Alcoholic by Kaveh Akbar

by Genevieve N. Williams

Kaveh Akbar writes with such spiritual risk and honesty that we as readers are brought into the liminal spaces of language, addiction, and displacement.

The Catalog of Broken Things by Anatoly Molotkov

by Anthony DiMatteo

The book offers a journey of disorder and disappearance. As in life, one must find a way.

Didi Jackson Reads

“On the Death of my Father”

His outsider art graces the album cover of Little Creatures

by the Talking Heads, and a vision of his dead

sister climbing down from Heaven

Sympathetic Magic

Annah Browning

This magic is also called the magic of correspondence or contagion — the properties of one thing leaping to another.In folk medicines around the world, it shows up in what has been called the doctrine of signatures…

Little World / After a Series of Rejections

by Sawnie Morris

First Place, Ruth Stone Poetry Prize

You can safely e merge to sit with magenta tulips ,

orange day lilies shouting

Terrorists

by Donald Levering

Runner Up, Ruth Stone Poetry Prize

God don’t let that be

my bombshell daughter naked

in a sleeping bag on a public bench

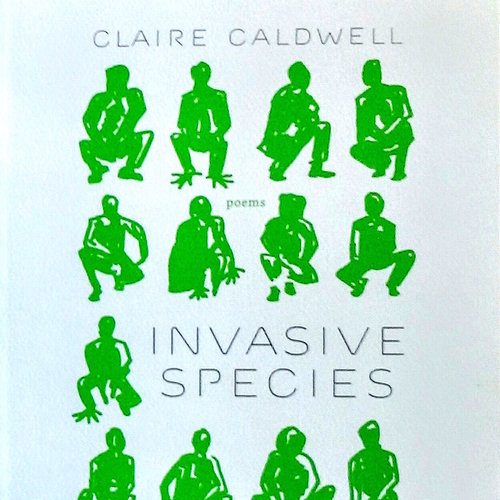

Invasive Species by Claire Caldwell

by Ariel Kusby

Caldwell’s poems manage to explore substantial themes with an intimate gaze; the humor is simultaneously empathetic and darkly cynical.

Alison Prine Reads

“Coming Out”

Alison’s poem, Coming Out, is featured in Hunger Mountain 21: Masked/Unmasked on sale now.

Wonderland of Words: An Interview with Matthew Dickman

by Lara Gentchos

I’m going to die, and I want my experiences, as much as I can control them — which is not much — to be experiences with art that makes me feel something.

Ruby Mountain by Ruth Nolan

by Cindy Lamothe

Nolan’s soft, subtle expressions paint these invisible terrains with a quiet, haunting power. The speaker’s thirst for her previous life is a mirage that beckons us forward…

Writing In Between: An Interview with Tyler Friend

by Breanne Cunningham

Most of what I write is love poetry. And a lot of it comes from dreams. A lot of it comes from lucid dreaming, that half-awake, half-asleep state.

When the Cake is Baked

Susan Browne

I had to find a way to diffuse these tense and often unbearable situations. One day while discussing a student’s poem, I blurted out, “Hey, the cake isn’t baked yet.”

We Are Pleased to Announce the Judges for Hunger Mountain’s 2016 Literary Prizes

The judges are: Janet Burroway- Howard Frank Mosher Short Fiction Prize Robert Michael Pyle – Hunger Mountain Creative Nonfiction Prize Lee Upton – Ruth Stone Poetry Prize Rita Williams-Garcia – Katherine Paterson Prize for Young Adult & Children’s Writing Janet Burroway, awarded the 2014 Lifetime Achievement Award in Writing by the Florida Humanities Council, is… Continue reading We Are Pleased to Announce the Judges for Hunger Mountain’s 2016 Literary Prizes

Two Poems

Chard deNiord

In steps at your command/down the plank of a tall

fast ship with the salt/of sex across its lips.

Milk

Julie Cadwallader Staub

Winner, Ruth Stone Poetry Prize

This goat kicked me only once,

as if to say she knows

I’m an amateur

Pink

by Kari Smith

Runner-Up, Ruth Stone Poetry Prize

like chrysanthemums, like tulips;

like the droopy pink heads of peonies

that filled our kitchen windowsill, spilling

over mason jars and plastic cups…

Time Under a Bridge

by Lisa Breger

Runner-Up, Ruth Stone Poetry Prize

I don’t want to leave this world:

My friends are in it, and there’s so much beauty.

Small Version of a Long Story

John James

Impalpable, transparent, a big man /

In a rabbit-coat turns twice, turns three times…

Five Poems

Lafayette Wattles

Saturdays my dad wakes beneath the still-bruised

sky. Then with number-crunching hands,

Definition

Kerrin McCadden

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#8f2866′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”] I once found a deer collapsed near a lake—sleek, immaculate, & unmoving except for its antlers, which swarmed with orange-&-black-speckled butterflies that obliterated the velvet beneath. Whatever word explains this, I don’t want to know it yet. —Matt Donovan The… Continue reading Definition

Kerrin McCadden