[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#372a55′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

June

In the beginning, don’t talk to your daughter, because anything you say she will refute. Notice that she no longer eats cheese. Yes, cheese: an entire food category goes missing from her diet. She claims cheese is disgusting and that, hello? she has always hated it. Think to yourself…okay, no Feta, no Gouda—that’s a unique and painless path to individuation; she’s not piercing, tattooing or voting Republican. Cheese isn’t crucial. The less said about cheese the better, though honestly you do remember watching her enjoy Brie on baguette Friday evenings when the neighbors came over and there was laughter in the house.

Then baguettes go too.

“White flour isn’t healthy,” she says.

She claims to be so much happier now that she’s healthier, now that she doesn’t eat cheese, pasta, cookies, meat, peanut butter, avocados, and milk. She tells you all this without smiling. Standing before the open refrigerator like an anthropologist studying the customs of a quaint and backwards civilization, she doesn’t appear happier.

When she steps away with only a wedge of yellow bell pepper say, “Are you sure that’s all you want? What about your bones? Your body is growing, now’s the time to load up on calcium so you don’t end up a lonely old hunchback sweeping the sidewalk in front of your cottage.” Bend over your pretend broom, nod your head and crook a finger at her.

Nibble, Nibble like a mouse, who is nibbling on my house? Cried the old witch, “Oh, dear Gretel, come in. There is nothing to be frightened of. Come in.” She took Gretel by the hand, and led her into her little house. Then more good food was set before Gretel, milk and cheese, with avocado, cookies, and nuts.

Your daughter stares up at the kitchen ceiling, her look a stew of disdain and forbearance. “Just so you know, Mom, you’re so not the smartest person in the room.” She nibbles her pepper wedge, and you hope none of it gets stuck between her teeth or she will miss half her meal.

Alone at night, nearly google Eating Disorder three times. When you finally press enter, you are astonished to see that there are 7,800,000 pages of resources with headings like Psych Central, Body Distortion, ED Index, Recovery Blog, Celebrities with Anorexia, Alliance for Hope, DSM IV.

Realize an expert is needed and take your daughter to a dietician. In the elevator on the way up, she stands as far away from you as she possibly can. Her hair, the color of dead grass, hangs over her fierce eyes. “In case you’re wondering, I hate you.”

Remember, your daughter is in there somewhere.

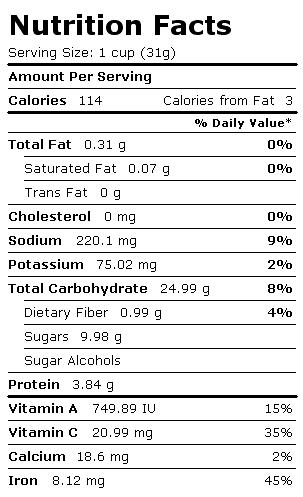

This dietician—recommended by a childless, 40-something friend who sought help in order to lose belly fat—looks at your daughter and sees one of her usual clients. She recommends 1400 calories a day, non-fat dairy, one slice of bread, just one tablespoon of olive oil on salad greens. You didn’t know—you thought you were doing the right thing, And you are now relegated to the dunce chair forever by your daughter who is thin as she’s always wanted to be.

The sixteen year old part of you—the Teen Magazine subscribing part of you that bleached your dark hair orange with Super Sun In and hated, absolutely hated, your thighs, the part that used to sometimes eat just a bagel so if anyone asked you what you’d eaten that day, you could answer, a bagel and feel strong—that part of you thinks your daughter looks good. Your daughter is nearly as thin as a big-eyed Keane girl, as thin as the eighth grade girls who drift along the halls of her middle school, their binders pressed to their collarbones, their coveted low-rise, destroyed-denim, skinny-fit, size double-zero jeans grazing their jutting hipbones.

100% cotton, toothpick leg, subtle fading and whiskering, heavy vintage destruction wash, low rise skinny fit, imported

She is as thin as her friends who brag about being stuffed after their one-carrot lunch.

“It’s crazy, Mom. I’m worried about Beth, Sara, McKenzie, Claire….” she says, waving her slice of yellow bell pepper in the air.

Google Eating Disorders again. This time click on the link, understandingEDs.com.

July

Don’t talk to your daughter about food, though this is all she will want to talk to you about. Spaghetti with clam sauce sounds amazing, she’ll say, flipping through Gourmet magazine, but when you prepare it, along with a batch of brownies, hoping she’ll eat, she’ll claim she’s always detested it. She’ll call you an idiot for cooking shit-food you know she loathes. “You know what, Mom,” she will say with her new vitriol, “I never want to be a chubby-stupid-no-life-fucking-bitch-leach-loser like you.”

After you slap her, don’t cry. Hold your offending palm against your own cheek, in a melodramatic gesture of shame and horror that you think you really mean. Feel no satisfaction. When she calls you abusive and threatens to phone child protective services, resist handing her the phone with a wry I dare you smile. Try not to scream back at her. Don’t ask her what the hell self-starvation is if not abuse. Be humiliated and embarrassed, but don’t make yourself any promises about never stooping that low again. Remind your daughter that spaghetti with clam sauce and brownies was the exact meal she requested for her 12th birthday, and then quickly leave the room.

Lovely’s 12th Birthday Brownies

2 STICKS unsalted butter

4 oz best quality unsweetened chocolate

2 cups sugar

4 eggs

1 cup WHITE FLOUR

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon vanilla

1 cup fresh raspberries

Preheat oven to 350°. Butter large baking pan. Melt together butter and chocolate over a very, very low flame or better yet, in a double boiler. Watch and stir constantly to prevent burning. Turn off heat. Add sugar and stir until granules dissolve. Stir in eggs, one at a time, until fully incorporated and the batter shines. Blend in vanilla, fold in the flour until just mixed. Add raspberries. Bake for 30 minutes. The center will be gooey, the edges must have begun to pull away from the sides of the pan. Try your best to wait until the brownies cool before you slice them. 1

Enjoy

Later, after you have eaten half the brownies and picked at the crumbling bits stuck to the pan, apologize to your daughter. She will tell you she didn’t mean it when she called you chubby, hug her and feel as if you’re clutching a bag of hammers to your chest.

“The hallmark of anorexia nervosa is a preoccupation with food and a refusal to maintain minimally normal body weight. One of the most frightening aspects of the disorder is that people with anorexia nervosa continue to think they look fat even when they are bone-thin. Their nails and hair become brittle, and their skin may become dry and yellow.” 2

Prepare meals you hope she will eat: buckwheat noodles with shrimp, grilled salmon and quinoa, baked chicken with bulgur, omelets without cheese. When you melt butter in the pan, or put olive oil on the salad, try not to let her see. Try to cook when she is away from the kitchen, though suddenly it is her favorite room, the cookbooks her new library. Feel as if you always have a sharp-beaked raven on your shoulder, watching, pecking, deciding not to eat, angry at food, and terribly angry at you.

Begin to have heated, whispered conversations with your husband—in closets, in the pantry, in bed at night. He wants to sneak cream into the milk carton. He wants to put melted butter in her yogurt. He wants to nourish his little girl. He is terrified.

You are angry, resentful and confused. You want help. You are terrified.

“She’s mean because she’s starving,” he says. “How you feel doesn’t matter.”

“Yes, but I have to live in this house too.”

“How you feel doesn’t matter.”

“Yes, but she used to love me.”

“This isn’t about you.”

Later, after you once again do not have sex, get out of bed, close the bathroom door behind you, close the shower door behind you as well, then cry into a towel for as long as you like. Ask yourself, is this about me?

September

Take your daughter to the doctor. Learn about orthostatic blood pressure and body mass index. Learn that she’s had dizzy spells, that she hasn’t had her period for 4 months. Worry terribly. Feel like a failure: like a chubby-stupid-no-life-fucking-bitch-leach-loser.

When the pregnant doctor tells your daughter that she needs to gain five pounds and your daughter starts to cry and then to scream that none of you-people live in her body, you-people have no idea what she needs, you-people are rude and she will only listen to herself. You-people (you and the doctor and the nurse) huddle together and listen. You don’t want to be one of you-people, you want to be hugging your frightened, hostile daughter who sits alone on the examination table. But she won’t let you. The doctor gives her a week to gain two pounds and find a therapist or she will refer her to an eating disorder clinic. You want your daughter to succeed. You want her to stay with you at home, to stay in her new high school, to make new friends, to laugh, to answer her body when she feels hunger.

You watch your daughter watch the doctor squeeze her pregnant belly between the cabinet and the examination table and you know exactly what your daughter is thinking—fat, fat, fat.

Before you leave, the doctor pulls you aside and tells you that your daughter suffers from “disordered eating.” She tells you to assemble a treatment team: doctor, therapist, nutritionist, family therapist. “You’ll need support; you’ll need strategies.”

You’ve never been on a team before. Ask the obvious question “Eating disorder vs. disordered eating? What’s the difference?” Get no answer. Try to go easy on yourself.

“Knowledge about the causes of anorexia nervosa is inconclusive, and the causes may be varied. In an attempt to understand and uncover the origins of eating disorders, scientists have studied the personalities, genetics, environments, and biochemistry of people with these illnesses. Certain personality traits common in persons with anorexia nervosa are low self-esteem, social isolation (which usually occurs after the behavior associated with anorexia nervosa begins), and perfectionism. These people tend to be good students and excellent athletes. It does seem clear (although this may not be recognized by the patient), that focusing on weight loss and food allows the person to ignore problems that are too painful or seem unresolvable.” 3

Remember, you were always there to listen to painful problems, to help. You kept your house purged of fashion magazines, quit buying the telephone-book-sized September Vogue as soon as you gave birth to her. Only glanced at People in the dentist’s office. So why? How? How did this happen to your family?

Karen Carpenter, Mary-Kate Olsen, Gilda Radner, Oprah Winfrey, Kate Winslet, Anne Sexton, Paula Abdul, Sylvia Plath, Princess Diana, Jane Fonda, Audrey Hepburn, Mariel Hemingway, Sally Field, Anna Freud, Elton John, Richard Simmons, Franz Kafka for Christ’s Sake

You should have never paid Cinderella to enchant the girls at her fourth birthday party. Cringe as you remember the shimmering blue acetate gown and the circle of mesmerized girls at Cinderella’s knees, their eyes softly closed, tender mouths slackened to moist O’s. Cinderella hummed Cinderella’s love song, she caked iridescent blue eye-shadow on each girl while they fell in love with her and her particular fantasy. Know in your heart that, even though you cancelled cable and forbade Barbie to cross your threshold, you are responsible. You have failed her.

After the doctor’s appointment, drive to your daughter’s favorite Thai restaurant while she weeps beside you and tells you she never imagined she’d be a person with an eating disorder. “If this could happen to me, anything can happen to anyone.”

Tell her, “Your light will shine. Live Strong. We will come through this.” Vague aphorisms are suddenly your specialty.

“I’m scared,” she tells you.

For the first time in months, you are not scared. You are calm. Your daughter seems pliable, reachable. For the entire car ride, the search for a parking space and the walk into the restaurant you are filled with hope. And then you are seated for lunch and she studies the menu for eleven minutes, finally ordering only a green papaya salad. Hope flees and this is the moment you begin to eat like a role model. You too order a salad, you also order Pho and salmon and custard and tea. Eat slowly with false joy and frivolity. Show her how much fun eating can be! Look at me, ha-ha, dangling rice noodles from my chopsticks, tilting my head to get it all in my mouth. Yum! Delicious! Wow! Ha ha! Ha ha! Ha!

October

Rejoice! Your daughter adds dry roasted almonds to her approved food list. She eats a handful everyday. She also eats eight-dollars-a-loaf mother-grain bread from a vegan restaurant across the river. You gladly drive there in the rain, late at night. In the morning, she stands purple lipped in front of the toaster, holding her hands up to it for warmth.

“People with anorexia nervosa often complain of feeling cold (hypothermia) because their body temperature drops. They may develop lanugo (a term used to describe the fine hair on a new born) on their body.” 4

Your daughter furiously gnashes a wad of gum. She read somewhere that gum stimulates digestion and she chomps nearly all day. You find clumps of gum in the laundry, in the dog’s bed, mashed into the carpet, stuck to sweaters. Seeing her aggressive chewing makes your skin crawl. Tell her how you feel.

“Why?” your husband demands. “How you feel is irrelevant.”

“Good for you,” your childless friend tells you. “Your daughter shouldn’t get away with railroading your family.”

“How’d that conversation go?” The therapist pinches a molecule of lint from her stylish wool skirt.

“She called me pathetic-cunt-Munchausen-loser.” Where did your daughter learn this language? You don’t even know what that means. Your daughter has been replaced by a tweaking rapper pimp with a psychology degree.

The therapist, in her Prada boots and black knit dress, speaks in a low voice. She has very short hair and good jewelry. Stylish, you think, your daughter will like her.

“She means you are making up her problems to get attention, Münchausen syndrome by proxy,” the therapist says.

You still don’t know what that means, so you volunteer information. “She chews gum.”

“They all do.”

“I hate that bitch,” your daughter shrieks in the car on the way home. “I’m never going back.” Remember to speak in calm tones when you answer. Remember what the therapist told you about the 6 C’s: clear, calm, consistent, communication, consequences…you’ve already forgotten one. Chant the 5 you do recall in your mind while you carefully tell your daughter that she certainly will go back or else. In between vague threats (your specialty) and repeating your new mantra, feel spurts of rage toward your husband for sending you alone to therapy with your anorexic daughter. Also feel terribly, awfully, deeply guilty for feeling fury. What kind of monster doesn’t want to be alone with her own child? During this internal chant/argument/lament cacophony, right before your very eyes, your daughter transforms into a panther. She kicks the car dash with her boot heel, twists and yanks knobs, trying to break the radio, the heater, anything, while screaming hate-filled syllables. Her face turns crimson while she punches and slaps at your arms. Pull over now. Watch in horror as she scratches her own wrists and the skin curls away like bark beneath her fingernails. All the while she will scream that you are doing this to her. Don’t cry or she will call you pathetic again. Remember that your daughter is in there, somewhere. Tell her you love her. Refuse to drive until she buckles into the backseat. Wonder if there is an instant icepack in the first aid kit. Wonder if there is a car seat big enough to contain her. Yearn for those long ago car seat days. Think, we’ve hit bottom. Think it, but don’t count on it. Then remember the last C: compassion.

For some reason, driving suddenly frightens you. When you must change lanes, your heart thunks like a dropped pair of boots, your hands clutch the steering wheel. You shrink down in your seat, prepared for a sixteen-wheeler to ram into you. You can hear it and see it coming at you in your rearview mirror. Nearly close your eyes but don’t; instead, pull over. Every time you get into your car, remind yourself to focus, to drive while you’re driving, to breathe. Fine, fine, fine you will be fine; chant this as you start your engine. Be amazed and frightened by the false stability you’ve been living with your entire life. If this can happen to you, anything can happen to anyone.

When your husband leaves town for business, worry about being alone with your daughter. Try not to upset her. When she tells you she got a 104% on her French test, smile. When she tells you she is getting an A+ in algebra, say, WOW! Don’t let her know that you think super-achievement is part of her disease. Don’t let on that you wish she would eat mousse au chocolat, read Simone de Beauvoir’s, Le Deuxieme Sexe and earn a D in French.

Begin to think that maybe you are always looking for trouble, Munchausen-by-proxy. Be happy when she has a ramekin of dry cereal before bed.

Hug her before you remember she won’t let you, and don’t answer when she says, “Bitch, get off me.”

In the middle of the night wake her and tell her that you miss her, that you’ve had a bad dream. Ask her to come and sleep in your bed. When she does, hug her. Comfort her. Comfort yourself. Remember how she smelled as a toddler, like sweat and graham crackers. Remember how manageable her tantrums used to be. Whisper over and over in her perfect ear that you love her. That she will get better. Know that she needs to hear your words, believe that somewhere inside she feels this moment. In the morning, look away while she stands, purple-lipped before the toaster.

When your husband dedicates every Saturday afternoon to your daughter, taking her to lunch, shoe shopping, to a movie, use the time to take care of you. Kiss them both goodbye and say with a forced lilt, “Wish I could come too.” Quickly shut the front door. Try not to register their expressions, the doomed shake of your husband’s head, your daughter’s eyes flat as empty skillets.

“Take a little me time,” your childless friend has suggested. “Get a facial…a massage…a pedicure, buy a cozy sweater, read Oprah Magazine.”

What to Do When Life Seems Unfair?

Do you ask, Why me?

What is your life trying to tell you?

How you choose to respond to difficult things

can mean the difference between a life of anger

…or joy…

Instead, take a long bath. Light aroma therapy candles and incense. Pour in soothing-retreat-bath-oil. Even though it is only eleven o’clock, mix a pitcher of Manhattans.

Mommy’s Manhattan, 2 oz blended whiskey, 1 oz sweet vermouth, 1 dash bitters, cherry

Play world music and pretend you are somewhere else. Except of course you aren’t. You know you aren’t somewhere else because as you were filling the tub you noticed raggedy bits of food in the drain.

Continue adding hot water. Wouldn’t she vomit in the toilet? Your daughter must be terrified for herself to leave behind Technicolor clues. Continue adding hot water. Drain the water heater. Notice, as the water level climbs, that your stomach is nearly the last thing to go under. Months of role-model eating have changed your body. Try to love your new abundance.

When your husband and daughter return and you are still in the tub, she slams her bedroom door. Your husband slumps on the toilet, his head in his hands.

Listen quietly.

“She pretended not to know where the shoe store was. We walked for forty-five minutes. Really, it was more of a forced march.”

Say nothing, though you feel more than a dash of bitters; you feel angry and tired of being angry. Stare at your wrinkled toes. You are each alone: your daughter in her room, your husband on the toilet, you in the tub. You’re each in your private little suffering-bubble.

“Exercise is verboten.” The doctor has given you both this directive.

“I know.” When his voice breaks and his hands shudder, get out of the lukewarm tub. Climb into his lap, and put your arms around him. Cling together.

November

Hooray! Your daughter has added whole-wheat pasta to her approved food list. At the doctor’s office, her blood pressure is amazing! She’s gained five pounds! You people are all smiling. This time in the elevator, your daughter stands right beside you. For days you are happy.

Until you find her in the kitchen blotting oil out of the fish fajitas. When you confront her, tell her that is anorexic behavior, she throws the spatula across the room.

“Persons with anorexia nervosa develop strange eating habits such as cutting their food into tiny pieces, refusing to eat in front of others, or fixing elaborate meals for others that they themselves don’t eat. Food and weight become obsessions as people with this disorder constantly think about their next encounter with food.”5

Your daughter claims oil gives her indigestion, the food in the drain is because of acid reflux, you are the one obsessed, you are the one who is sick, she is fine.

You say, “Bullshit.”

“Ssshhh,” your husband says. “Can we please have peace?” Like a middle school principal he calls you into his home office to tell you that she doesn’t need to be told every single moment that something isn’t right. “Stop reminding her,” he says. “Leave her alone. It’s hard enough for her without having to faceherproblemeverysingleminute.”

He can’t even say the word anorexic.

Properly censured, return to the kitchen. Your daughter eyes you with smug satisfaction and eats barely one half of a whole wheat tortilla—no cheese, no avocado—with her fish. A vise of resentment tightens around you. Anorexia has rearranged your family.

di·vorce [di-vawrs, –vohrs] – noun, verb -vorced, -vorc·ing.

1. a judicial declaration dissolving a marriage in whole or in part, releasing the husband and wife from all matrimonial obligations.

3. total separation; disunion: a divorce between thought and action.

4. to separate by divorce: The judge divorced the couple.

5. to break the marriage contract between oneself and (one’s spouse) by divorce: She divorced her husband.6

Fantasize about how you will decorate your living room when you live alone, when you disjoin, dissociate, divide, disconnect. Imagine your new white bookcases lined with self-help books:

The Best Year of Your Life

The Power of Now

When Am I Going to Be Happy

Course in Miracles

Get Out of Your Own Way

Essential Living

The Last Self-Help Book You’ll Ever Need

Feel Welcome Now

Why Dogs Make Us Happy

You’re filled with a thrilling flutter of shame. When did this become about you?

Snoop. Look through your daughter’s laundry basket for vomity towels. Stand outside the bathroom door and listen. Look in the trash for uneaten food. Though you want to call her school to see if she is eating the lunch she packs with extreme care everyday (non-fat Greek yogurt, dry-roasted almonds, one apricot) Don’t. When you find her journal, don’t read it. Her therapist has told her she should record her feelings, her fears. You are desperate to know what it says. The journal screams and whispers your name all day long. Later, when you are folding laundry, and can no longer resist, go back upstairs to her room and find that she hasn’t written a single thing. Despair.

At Thanksgiving you realize the difference between Grandpa’s overdrinking and your daughter’s undereating is slim. Deny, deny, deny. The rest of the relatives are acutely aware, and between watching alcohol consumed and food left on the plate, your gaze ping pongs from your daughter to your father. Both start out charming enough. Your daughter sets a beautiful table: plump little pumpkins carved out, their tummies filled with mums and roses, thyme and lavender, slender white tapers rising up from the center and flickering light over the groaning table. But as the afternoon progresses and Grandpa’s wine glass is filled and emptied again, the turkey carcass is removed and pies emerge, your daughter’s mood fades to black.

“Junk in the trunk,” Grandpa slurs, patting your abundant rear as he walks behind you. “Next year, we should all fast.” You want to kill him.

Your starving daughter pushes away her plate, her face pinched, disappointed, angry. You can see her mantra scroll across her eyes like the CNN news crawl…loser… failure….pathetic…chubby…. What she calls herself is neither worse nor better than what she calls you. It’s a revelation and you repeat your C’s: calm, consistent, compassion, communication, calamitous, collapse, cursed, condemned.

At the hotel, your daughter insists on taking a long walk, stretching her stomach she calls it. You and your husband say no. She throws a tantrum and you are all trapped in the hotel room, staring at a feel-good family movie involving a twelve-step program, cups of hot coffee, and redemption.

God grant us the serenity to accept the things we cannot change,

courage to change the things we can,

and wisdom to know the difference.

By the next doctor visit she’s lost six pounds and she cries and cries. Your body goes cold. You feel like a fool, slumped on the pediatrician’s toddler bench, staring at the repeating wall paper pattern: the dish running away with the spoon, the gingerbread man, cat and the fiddle, Little Miss Muffet, curds and whey; Mother Goose and her fluffy outstretched wings hovers above them all with bemused tolerance and extreme capability. An infant cries in the next room and you yearn for the days of uncomplicated care and comfort.

“I am so angry,” your voice is not angry, it is depleted. You are not competent as Mother Goose, you are the woman trapped in a shoe, with only one child and still you don’t know what to do.

Your daughter agrees to go on anti-depressants, to help her adjust to her changing body, the doctor says. When you leave the office you drive straight to the pharmacy and then to a bakery and watch her consume a Prozac and a chocolate chip cookie. Her eyes, her giant, chocolate pudding eyes drip tears into her hot milk, her hand shakes.

“Antidepressants increased the risk compared to placebo of suicidal thinking and behavior (suicidality) in children, adolescents, and young adults in short-term studies of major depressive disorder (MDD) and other psychiatric disorders. Anyone considering the use of [Insert established name] or any other antidepressant in a child, adolescent, or young adult must balance this risk with the clinical need. …Patients of all ages who are started on antidepressant therapy should be monitored appropriately and observed closely for clinical worsening, suicidality, or unusual changes in behavior. Families and caregivers should be advised of the need for close observation and communication with the prescriber.” 7

“It’s not my fault,” she sobs.

“Oh, Lovely.” You shake your head, review the many theories that Google dredged up: genetic predisposition, a virus, lack of self-concept, struggle for control, post-traumatic stress disorder.

“I didn’t want this,” she says.

“Of course you didn’t.”

“The voice scares me.”

“Voice?”

“My eating disorder. Tells me I suck and it never shuts up, only if I restrict.”

Pay attention. This is language that you haven’t heard before. Watch. Listen. Mood swings. Suicide ideation. Changes in behavior. Be terrified about everything. Ask with nonchalance, “This voice, is it yours?”

Her skin goes pale, the transparent blue of skim milk.

Later, when you are alone, call your husband on his cell phone. He is standing in line, waiting to board a plane. Don’t care. Scream into the phone. Imagine your tinny, bitchy voice leaking around his ear while men holding lattes, women with Coach briefcases, students and grandmas try not to look at his worn face.

“Say it out loud.”

“She has an eating disorder,” he mumbles.

“Not fucking enough,” you shriek, your hands shake. Until he says it loud, admits it fully to himself, you will not be satisfied. You may have gone crazy.

“My daughter is anorexic. There.”

You let it lie.

“Are you happy now,” he whispers.

Oddly enough, you are momentarily happier.

March

She’s back. Your daughter dances into the kitchen, holding a piece of cinnamon toast. She wants milk, 2%. She also wants a cookie and pasta, a banana, a puppy and a trip to Italy.

“I want some of those,” your husband whispers, nodding to the prescription bottle on the windowsill.

You want this to continue. She may not be eating Brie and baguette, but she’s laughing. Her collarbones are less prominent. She’s. Given. Up. Gum.

“The voice is leaving, Mom” she confides. “It polluted everything.” She smiles, hopeful and charming, so wanting to please. Even though it may not completely be true about the voice, she wants it to be and for now desire has to be enough. That she talks about the voice without anger or tears takes a grocery cart of courage.

“Quit worrying and watching me so much,” she says.

You nod and smile. You will never quit worrying and watching.

Weak spring sunlight fills your kitchen. Your daughter, with a hand on her hip, stands before the open refrigerator, singing. You still are not certain keeping her home and in school is the right choice. A clinic may be inevitable. You’ve followed advice, you have your team, yet letting go of watching and worrying would require a grocery cart full of courage that you do not have. Just yesterday you checked her web history and found she’d visited caloriesperhour.com.

“I’m hungry,” your daughter says.

You haven’t heard those words from her for nearly a year. Grab onto them, this is a moment of potential. Look for more. Remember them. String them together. Write post-it notes for the inside of your medicine cabinet. Almonds! I hear me! 2% Milk! I’m hungry! Dream of the day when your cabinet door will look like a wing, feathered in hopeful little yellow squares.

Then Gretel, suddenly released from the bars of her cage, spread her arms like wings and rejoiced. “But now I must find my way back,” said Gretel. She walked onward until she came to a vast lake, “I see no way across….”

Picture you people: your husband, the physician, the therapists and nutritionist, family members—all standing across the water, waving, calling; a part of her remains listening on the other side, afraid to lose control, afraid to fail, afraid to drown.

Open your arms wide. Your daughter is getting nearer. Know that it is up to her. Say her lovely name. Know that it is up to her. Shout her lovely name.

1 Lovely’s 12th Birthday Brownies are based on a recipe at http://www.cooks.com/rec/view/0,1710,155163-239207,00.html

2 From NAMI.org, the National Alliance on Mental Illness. http://www.naminh.org/NAMI-Fact-Sheet-Eating-Anorexia.pdf

3 From NAMI.org, the National Alliance on Mental Illness. http://www.naminh.org/NAMI-Fact-Sheet-Eating-Anorexia.pdf

4 From NAMI.org, the National Alliance on Mental Illness. http://www.naminh.org/NAMI-Fact-Sheet-Eating-Anorexia.pdf

6 Definition of divorce is from Dictionary.com

7 From http://www.fda.gov/

Art by Kerri Augenstein

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#372a55′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

[av_one_half first]

[/av_one_half]

Natalie Serber received an MFA from Warren Wilson College. Her work has appeared in The Bellingham Review and Gulf Coast, among others, and her awards include the Tobias Wolff Award. She teaches writing at various universities and lives with her family in Portland, Oregon.

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#372a55′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]buy shoes | Sneakers