[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#339999′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

Most writers are familiar with the advice, “Show, don’t tell.” It is as simple as it is vague and like many aphorisms, it’s largely not practical or useful on a daily basis.

A quick word on telling—there are numerous places where telling or exposition is entirely appropriate. Not every aspect of a story deserves equal reality on the page. Rather than showing everything, a discriminating writer will find which things should be shown while using summary, exposition, or telling for the rest.

So, assume, dear writer, that you have decided that this is indeed something which justifies the extra care and attention required to show it.

How? How do you show instead of tell?

Begin with the body. Excluding speculative fiction or magical realism stories, which might be told from the perspective of a super-intelligent shade of the color blue, every character has a body and so does every reader (even readers of spec-fic).

The body shows much of what the character thinks and feels through body language, which includes facial expressions, posture, gesture, eye movement, touch, and use of space. According to Albert Mehrabian in his 1972 book Silent Messages, only about 7% of meaning is conveyed through words alone. While this is an oversimplification, it’s safe to say that much of human communication depends on nonverbal cues. As Jeff Thompson notes in his essay “Is Nonverbal Communication a Numbers Game?”, “…when trying to understand others, a single gesture or comment does not necessarily mean something. Instead, these theories allow us to take note and observe more to get a better understanding of what is going on.”

For story purposes, body language can be used to show emotions, characterize people, advance the plot, respond to dialogue, or break up the dreaded wall of text, especially if a character has a long or complex utterance.

When showing emotions, word choice is key. For example, consider the following:

- Max stalked through the darkened house. In the kitchen, he yanked open the fridge and peered in, eyes darting from side to side. He snatched the plate of leftover meatloaf.

- Max crept through the darkened house. In the kitchen, he pried open the fridge and peeped in, eyes flicking from side to side. He selected the plate of leftover meatloaf.

What is Max’s emotional state in Paragraph 1? What is their state in Paragraph 2?

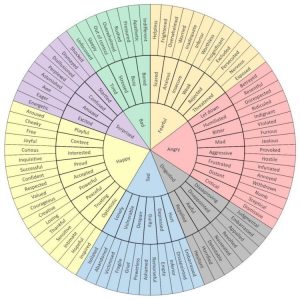

Many writers, myself included, struggle to name and categorize emotions precisely, so I keep the Wheel of Emotions handy. I first saw this in a craft class by Eric Witchey and he said he found it on the internet. In any case, it’s useful so I’m sharing it with you.

Body language can also characterize, breathing life into flat characters or differentiating characters who otherwise might be too similar. Figure out your characters’ ticks, mannerisms, marks of class, status, culture, and age. For example, a young character is going to move differently than an older character. A character from York, UK is not going to flip someone off the same way their friend from New York, USA would.

The big six emotions are: fear, anger, disgust, sadness, happiness, and surprise. I highly recommend The Emotion Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Character Expression by Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi. I’ve included a list of a few physical manifestations of each emotion at the end of this article.

In Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, a lackadaisical doctor is characterized by his actions: “…Yossarian, the private, reported instead to the dispensary with what he said was a pain in his right side. ‘Beat it,’ said the doctor on duty there, who was doing a crossword puzzle.”

In Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bible, Nathan’s actions serve to advance the plot, by showing the reader his determination to convert Orleanna: “He’d park himself on our dusty front-porch steps, fold his suit jacket neatly on the glider, roll up his sleeves, and read to me…”

In Karen Russell’s Ava Wrestles the Alligator, actions underscores both Ava’s indecision as the Bird Man tries to drew her into his world and his confidence:

“Ava.” He grins. “Can you keep a secret?” He reaches a hairy hand over the canal and holds two fingers against my lips.

I just nod. “Yes, sir.” I say politely…

“Listen to this, Ava.”

I inch forward until I am standing at the edge of the pier.

The Bird Man leans towards me…his thin fingers curled around the rail…The Bird Man locks eyes with me again, that agate, unnervingly fixed stare, and purses his lips.

Body language can also be used to respond to dialogue, where characters are literally showing their response. There are three ways to do this.

1. Actions support dialogue:

“You shouldn’t have waited up,” Julian said.

“Don’t think I don’t know what you’re up to,” she said, smiling/happily/with a grimace as she stared out the window.

2. Actions replace dialogue:

“How was Ed’s visit?” Claire asked.

Sarah swallowed and blinked back tears.

3. Actions that are at odds with dialogue:

“Did you eat all the cookies?” Mom put her hands on her hips.

“Well, someone did.” Dennis tipped his head towards his brother and raised his eyebrows.

In Frank Herbert’s Dune, Paul and Leto’s actions reinforce their words. Bonus points to Herbert for the subtle switch of character tags (the Duke because Leto) as the characters resolve their differences and re-establish a warm, father-son relationship.

The Duke stopped across from Paul, pounded the table…”Are you defending him?” the Duke demanded.

“Yes.”

“He’s getting old. That’s it. He should be—”

“He’s wise with much experience,” Paul said. “How many of Hawat’s mistakes can you recall?”

“I should be the one defending him,” the Duke said. “Not you.”

Paul smiled.

Leto sat down at the head of the table, put a hand over his son’s …

In Brent Weeks’ The Night Angel trilogy Durzo avoids a conflict with his response to Gwinvere’s insulting gesture:

It took all her strength to spit in the beer and set it on the counter with a shadow of nonchalance.

“Well, it’s tough to be a victim of circumstance,” Durzo said…He picked up the beer, smiled at Gwinvere over the spit and drank. He finished half the beer at a gulp and…poured the rest of [it] onto the floor and set the glass carefully on the bar.

Actions can also be used to break up walls of text suchs as monologues, stirring speeches, outpourings of emotion, or when the author has started waxing poetic in their prose, especially when describing setting or summarizing backstory.

While a soliloquy, such as Lady Macbeth’s speech from the play Macbeth, works perfectly well when acted on a stage, the written version can be a bit of a slog without an actor to breathe life into the Bard’s prose.

They met me in the day of success: and I have learned by the perfectest report, they have more in them than mortal knowledge. When I burned in desire to question them further, they made themselves air, into which they vanished. Whiles I stood rapt in the wonder of it, came missives from the king, who all-hailed me ‘Thane of Cawdor;’ by which title, before, these weird sisters saluted me, and referred me to the coming on of time, with ‘Hail, king that shalt be!’ This have I thought good to deliver thee, my dearest partner of greatness, that thou mightst not lose the dues of rejoicing, by being ignorant of what greatness is promised thee. Lay it to thy heart, and farewell.

Consider which actions you might add to make this work better on the page. How would you write this in a novel or short story instead of as a play? Yes, I’m suggesting we edit William Shakespeare, at least as a thought exercise to help us practice using body language to show emotions.

How could you use emotions to show Lady Macbeth’s agitation, her anger, her fear, her greed and ambition, her hope?

We all know what we’re supposed to do but remembering how to show these emotions can be hard in the heat of a writing session. Feel free to use the below appendix to get you started on showing.

The Six Emotions and a few examples of how they can be shown.

- Fear

-

- Posture

- Self-hugging

- Keep back to wall

- Face

- Pale/Pallid

- Glassy/Staring eyes

- Body

- Hunched shoulders

- Voice

- Shrill

- Talking to self

- Movement

- Trembling

- Moving fast/in spurts

- Grabbing onto others

- Flinching

- Tried and True (Cliché Alert!)

- Heart troubles—beating fast, thundering, stopping, skipping a beat

- Heavy breathing

- Wide eyes

- Posture

- Anger

-

- Posture

- Embiggening

- Hands up

- Violating others’ personal space

- Face

- Baring teeth

- High chin

- Grinding teeth

- Body

- Closed body

- Voice

- Interrupting

- Deepening voice

- Movement

- Rolling up sleeves/loosening collar

- Being loud

- Slamming things

- Hitting things

- Kicking objects

- Stomping

- Tried and True (Cliché Alert!)

- Heart troubles – pounding/beating/ thundering/etc.

- Heavy breathing

- Narrowed eyes

- Posture

- Disgust

-

-

- Posture

- Narrow stance/feet together

- Toes curled up

- Face

- Rubbing nose/mouth

- Eyebrows low and pinched together

- Open mouth, tongue slightly forward

- Body

- Rolling shoulders

- Voice

- Spitting or coughing

- Cover nose with hand/arm/shirt

- Movement

- Leaning away

- Jerking away from contact

- Using a shield

- Wincing

- Tried and True (Cliché Alert!)

- Wrinkled nose

- Cover mouth

- Vomiting

- Posture

-

- Sadness

-

- Posture

- Stooped

- Hands loose, empty

- Limbs close to body

- Face

- Covering with hands

- Brows furrowed

- Puffy/red eyes

- Sniffing

- Body

- Holding shoulder/arms crossed

- Voice

- Sore throat causes low/scratchy voice

- Flat/monotone

- Movement

- Heavy-footed walk

- Clumsy

- Rubbing/pressing chest

- Slow, lack of energy

- Tried and True (Cliché Alert!)

- Heart Troubles – aching/breaking

- Crying

- Choked voice

- Posture

- Happiness

-

- Posture

- Upright (proper)

- Stretched out, wide, open

- Face

- Upturned

- Tears of joy

- Raised cheekbones (from smiling)

- Body

- Arms out (hug the world)

- Voice

- Rapid cadence

- Humming/singing

- Light/higher voice

- Movement

- Fluid, big or broad

- Stepping lightly, skipping, hopping

- Satisfied, catlike stretch

- Nodding, leaning in, engaged

- Tried and True (Cliché Alert!)

- Heart fluttering

- SMILE

- Laugh/giggle/chuckle

- Breathless

- Posture

- Surprise

-

- Posture

- Tipping/turning head away

- Stiffened, rigid, frozen

- Face

- Eyes squeezed shut

- Whites of the eyes visible

- Hiding face

- Body

- Gripping the head/covering ears

- Touching throat

- Using a shield

- Voice

- Rise in pitch/volume

- Bark of laughter

- Unplanned questions—“What the—?”

- Stammering/Stuttering

- Movement

- Freeze

- Back away

- Grab/hug someone

- Shake head

- Tried and True (Cliché Alert!)

- Heart Troubles—skipping a beat, stopping

- Hand to chest

- Scream/squeal/shriek

- Mouth open in “O”

- Posture

Sources:

Mehrabian, A. (1972). Nonverbal Communication. New Brunswick: Aldine Transaction.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/beyond-words/201109/is-nonverbal-communication-numbers-game

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#339999′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

[av_one_half first]

[/av_one_half]

[av_one_half]

Molly Martin is an Assistant Fiction Editor at Hunger Mountain. She is a motorcycle-riding, combat veteran turned linguistics nerd. When not working on her own stories, she loves to read speculative fiction, drink tea, and vigorously defend the serial comma.[/av_one_half]

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#339999′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]bridge media | NIKE