Miss Pratt and Miss Avery come all the way from Kansas City. They’re part of a volunteer program aiming to bring charm to rural Kansas. Gran calls it “Social Education,” a term she lifted from the brochure. When Gran drops me at her church, where the classes are held, she says, “I pulled a lot of strings to get you in.” I imagine Miss Pratt and Miss Avery as marionette dolls. Gran positions them over a stage, Miss Pratt curtsies, and Miss Avery twirls, but I’m the one dangling at the bottom of Gran’s manipulation. Gran says it’s almost as good as the classes she took as a girl, where she met her best friends for life. The motto of the program is Teaching the Art of Sense and Civility. There are twenty-seven girls enrolled in the school. Miss Pratt is in charge of etiquette, while Miss Avery instructs dance. I’m told it’ll be a long time before I work with Miss Avery.

I’m placed into the class “Introduction to Social Skills.” I have to sit at a table with the eight- and nine-year-old girls. At fifteen, I tower above them, an awkward giant. Miss Pratt has a conductor’s wand, and she walks in circles around our table. When she isn’t using it to point out a misbehaving child or piece of misplaced silverware, she taps it on the palm of her other hand to emphasize what she’s saying or mark the passage of time. Her circling reminds me of kindergarten, and I keep expecting her to say, “Duck, duck, goose!” and start running with some little girl chasing after her.

We role-play how to meet someone. We meet each other. I meet all six of the third- and fourth-grade girls who sit at my table. At least ten times. According to Miss Pratt, I never introduce myself properly. Or show appropriate interest in others. She tells me this while tapping the wand against her palm. She wears the proper white gloves that we all have to wear. Her lips are red and sharply outlined with darker red. She doesn’t smile at me the way she smiles at the other girls.

The girls who are my age sit at the table designated for the advanced version of my class, called “The Power of Good Social Skills.” They’ve been in the program for seven years, since the third grade, the age a girl typically begins charm school and cotillion, with the exception of Candace Sherman. Candy, as Miss Pratt and Miss Avery call her, has been studying since kindergarten. I wonder if they’d even come all the way out here if it wasn’t for her. Miss Pratt always uses Candace as an example of how to do something correctly. “See how Candy stands?” she’ll ask, and then Candy will stand for us. After she’s finished standing, Miss Pratt’s smile softens and she assures us that someday we’ll all be that poised. “Candy’s been working at this longer than the rest of you,” she says, scanning the girls. Making eye contact with all of them. But never me. Who will never learn to stand. Or flutter my pinkie as I pour and sip tea.

“You girls mustn’t compare yourselves to Candy too much,” Miss Avery interjects. “Candy plans on being a model. In fact, with a little help from us, she’s already had a job.” I wonder if Candace has done anything but the pictures in the brochure. That’s when Miss Avery looks at me, frowning. Like she knows what I’m thinking. She looks away quickly and continues, “But all you future debutantes of America, remember this! Proper sitting, standing, walking and pivoting techniques are not just for models! They’re for all young ladies who want to be sophisticated and graceful.”

I tell Mama about the class when I visit her at the sanitarium, hoping she’ll understand the severity of the situation. Come to her senses, get discharged and withdraw me from the program. Move back home and take charge. But Mama doesn’t always hear me. On the one good day, Mama looks at me like she’s confused. “Good sense can’t be taught,” she says. “You’re either born with it or you’re not.” Mama doesn’t understand why she has to tell me something so simple, so she lights another Salem. And hides in the blue cloud of smoke because she knows I can’t get to her there.

The younger girls at my table make faces whenever Miss Pratt is busy at the other two tables. The second table is for “Developing Social Intelligence,” which I’ll have to take next, before I can move into the appropriate age bracket. Having met the girls at my table as many times as I have, I know all their names by heart. Katie, Wilma, Mary, Lizzie, Tatiana and Sara. I do not like them. They stick their tongues out and sneer at me. They push their noses into pig snouts using gloved fingers. But when Miss Pratt comes floating back, their smiles return. Flashing pearly teeth and batting eyelashes like frantic butterflies, they tuck their hands back into their laps, little praying angels. Miss Pratt looks at them like an adoring mother and says, “So much of charm school is learning one’s place.” She looks at me but doesn’t smile.

“Today we have a surprise!” Miss Pratt exclaims. Her cheeks look like there are gumballs stuck inside them and are rosy with pink blush. She has us stand in two rows, one on each side of the big room, so we face each other. Miss Pratt and Miss Avery pace the wide open space between. They look like China dolls, rigid like porcelain. They don’t seem to touch the ground when they walk. Especially Miss Avery, who glides across the coffee-stained, beige-colored carpet. The area where everyone gathers after Sunday services to eat and talk and spill.

“You future debutantes of America have been working so hard,” Miss Avery says, her blond hair curling around her face like a frame and bouncing ever so slightly as her head bobs up and down with enthusiasm. “We thought you deserved a little treat!” She walks as if she were on a runway. The way the Miss America contestants walk across the television screen. The catwalk. She also looks like the fake Barbie I nailed to the back of the shed like Jesus. I see Miss Avery crucified. Her tiny high-heeled feet wriggling about. Trying to be graceful without any footing as she bleeds out.

“We are going to give each other manicures!” Miss Pratt says, raising her arms so they arch around her head. Like Vanna White on Wheel of Fortune. Bringing attention to her hair, her face and her smile. She’s already confessed to having her teeth professionally bleached. Miss Avery said the sign of true friendship is when one gal shares her beauty secrets with another. Miss Avery and Miss Pratt’s teeth are so white they glow in the dark. They could be hostesses on Wheel of Fortune too.

I just finished my term paper even though it isn’t due until next Friday. The topic: famous women in history. If we didn’t know who to write about, we could draw a name from a hat, but I knew who I wanted to do: Joan of Arc. I’ve always wanted to know more about her. In my research, I learned about Saint Catherine of Alexandria, who came to Joan in visions as a guiding light. Saint Catherine was the famous virgin-martyr who was sentenced to be executed on a breaking wheel. Later, the breaking wheel was renamed the Catherine wheel in her honor.

I’d assumed the Wheel of Fortune came from the breaking wheel. Like how “Ring Around the Rosie” is actually about the Black Death, when the children didn’t fall down; they dropped dead. But then Daddy explained how the Wheel of Fortune comes from divination and the Tarot. He went to Mama’s room where no one sleeps anymore and came back with a deck. He said it was Mama’s, but it’s obvious he uses it himself. Which made me love him even more. The vulnerability of him consulting a glorified pack of playing cards. He said he draws that card a lot. The Wheel of Fortune. He draws it more than he would like. He said it represents the inexorable rise and fall of fortune. “In other words,” he said, “when the shit hits the fan, you have to keep on going. Take the blows; don’t give up.”

That’s not the same as the breaking wheel, which was a torture device used in the Middle Ages for capital punishment. The condemned person was tied to it and bludgeoned. The standard practice was to strike the legs and arms to keep the person from dying right away. Their suffering served as punishment. But there were also the blows of mercy. Mercy blows aimed for the head and torso, so the person would die more quickly. Otherwise a broken man or woman could last for hours, even days. Their shattered limbs were braided into the spokes, and the wheel was hoisted atop a pole in the town square as public warning. Left, dead or alive, for carrion birds to feed upon.

Miss Pratt sets her wand carefully on a table, like it’s a part of her body. A prosthesis. Something she doesn’t want to have too far away—the way a child acts about a security blanket. She and Miss Avery each claim a row. Miss Pratt takes my row. I stand somewhere in the middle and forget to breathe. It isn’t until Miss Pratt reaches Sara, who is next to me, that I realize why the instructors have been asking the students to take off their gloves.

Miss Pratt nods her head, and Sara takes her cue and removes her small white gloves. She pulls at each one like she’s presenting Miss Pratt with a special treat. Like she’s unwrapping a gift. As if her hands are really diamonds or white chocolate. When Mama was obsessed with footbinding, she told me how some Chinese women seduced their husbands. Instead of undressing, they slowly unwound the binding cloth. The binding cloth was ten feet long and two inches wide. They unwound it until their dainty, deformed feet were exposed. Cloven-shaped and putrid smelling, these feet were coveted by their lovers.

I watch Sara and Miss Pratt from the corners of my eyes. My own hands swell within the confines of velvety white cotton, bloating the way Mama bloated because of her anti-psychotic medication. By the time it’s my turn, my hands will be too swollen to come loose from Gran’s hand-me-down gloves. Either that or the seams of the gloves will bust. Burning hot, my fingers and palms tingle, too fat for circulation.

Miss Pratt takes Sara’s hands into her own and caresses them. Sara’s fingers look carved like she’s a China doll too. Miss Pratt lifts them, one by one, to look closer. She eyes Sara’s nails, which are not cut too short or left too long. In my gloves lurk calloused fingers, shredded cuticles, and nail beds full of dirt, caked with blood from picking scabs.

“Exquisite little half-moons of smoothly finished and sparkling clean fingernail,” Miss Pratt says as if she’s a food critic describing French cuisine. Like the dinner we’re preparing for that will mark our transition from one level to the next. For some of the girls, it will mark graduation. Someone like Candace Sherman will go to finishing school. Finishing is supposed to imply the act of perfecting. Adding the final touches to a masterpiece. But I think it sounds like the girl is finished. Done for. “That’s all she wrote,” like Uncle Billy would say. I told Mama my theory, thought she’d laugh. Be proud of my dark sense of humor. My feminist inclinations. But she didn’t seem to hear me. Aside from the involuntary twitching, her face stayed blank. No expression. So I repeated myself. The words sounded over-rehearsed and heavier the second time. I raised my voice, but she still didn’t hear me.

Sara’s skin is almost as white as the instructor’s gloves holding them. So white they turn powder blue, powder blue like she’s more dead than alive. I think about my name. Not Fig, but Fiona, which is also Gran’s name. Fiona means “fair and white.” Sara means “princess.” I know because I read The Little Princess and that was the heroine’s name. Miss Pratt’s holding her breath the way people do when they’re impressed. She lets it out, a little puff of air accented by delight. Under her application of blush her cheeks burn a true pink. “Perfection,” she announces. But she doesn’t move on like everyone expects her to do. As she’s done before. I’m not surprised. She knows I’m next. Finally, she takes her position in front of me. She clears her throat to signal that it’s my turn now.

At the first class I attended, Miss Pratt tried to be nice. She gave me a booklet (which serves as the textbook) and promised to go over it with me after class. But then there was the incident regarding my name, and everything changed. Gran had introduced me as Fiona after telling me in the car it’d be best if no one learned my nickname. So Miss Pratt introduced to me to the other girls as Fiona. She introduced me as Fiona to girls I already knew. From school or Gran’s church. Candace was the one to point out that no one calls me Fiona. Candace said, “I think it’s sweet that you tried,” and smiled the smile the instructors praise her for.

“I’m not sure I agree, Candace.” Miss Pratt said, making the hard C at the start of Candace’s name even harder and letting the soft C at the end hiss longer than it should. To emphasize that Candy is a nickname too. “Remember, dear, some nicknames are meant as terms of endearment.”

Miss Avery started listing off becoming nicknames, beginning with Trixie and ending with Candy. To prove their love. Then they asked what mine was. When I told them, their cheerful demeanor changed. “Like night and day,” which is one of Gran’s favorite things to say. Those three letters told Miss Pratt all she needed to know. She didn’t ask how I’d come to get the nickname, like most people do. Instead she said, “Well, that’s not very attractive, is it? It reminds me of prunes, and we all know what those are for.”

This sent a case of giggles around the room. And later, when no adults were around, the girls called out, “Hey Prune!” and shouted, “Diarrhea, diarrhea!” Their shouting has a sing-song quality. The words reverberate. At night in bed I can still hear them taunting me. But the worst part is Miss Pratt’s revenge. I think she thinks I tricked her into thinking I was someone else.

Miss Pratt clears her throat again. And I know I can’t just stand here like I don’t know what to do. She is tall in her high heels, those shoes that make it look like she doesn’t have any toes. As I tug at the white glove on my left hand I see the rows of girls in front of me and to my sides. They bend at the edges, like we’re inside a crystal ball. As if the world is collapsing at the sides. Their faces and bodies warp into funhouse mirror reflections and I can hear every breath and whisper, each girl magnified by some invisible microphone, feedback included. The glove slips off. Faster than I’d expected, it falls. Even the hush of it hitting the carpet is audible and my naked hand acts of its own accord. Trying to take cover. My hand hides behind my back, instead of being seen, instead of starting in on the other glove.

“Both gloves,” Miss Pratt instructs. Her voice is as clear and cold as running water.

The fluorescent lights hang low beneath the drop ceiling. One of Uncle Billy’s jobs is to un-drop ceilings like these that were all the rage in the 1970s. “That and shag carpeting,” Uncle Billy said. Un-dropping involves a crowbar, a sledgehammer and a shop vacuum. He showed me the original ceiling he’d exposed in one of the old buildings downtown. There it was. At least ten feet above where the drop ceiling had been. Like it was heaven. Made from what he called antique ceiling tin. He let me climb on the scaffold to see it up close. To touch what he called his Sistine Chapel. The white paint had peeled off long ago, and the tin had a green patina clinging to its surface like an exotic emerald moss. The kind from a fairytale.

The plastic covers over the fluorescent lights are cracked or broken, and the yellow light quivers from harsh to harsher. My other glove comes off, and this time I let it drop because I don’t know what else to do. I think about the booklet, the one Miss Pratt had promised to go over with me but didn’t. I took it home and read it cover to cover, including the section on hand care: A hostess’s hands are what a guest sees most as they are served food and drink. I read about unsightly cuticles and how nails that are the wrong length or color can announce a tacky woman. I thought they’d lined us up so they could pair us off; I was still trying to figure out how to get out of the actual manicure. I should’ve known they’d check. I just wasn’t sure we were ever allowed to take off our gloves. Like the Muslim women Mama told me about—the ones who can never take off their veils. The yellow light turns my skin into something grotesque. A Francis Bacon painting, the contemporary artist Mama loves. “His work is so visceral,” she’ll say.

On my wrist the open sore awaits. For me it’s as un-removable as a tattoo because I cannot leave it alone. It doesn’t have a scab. I peel the scabs off as soon as they form. Right now the blood is coagulating. The veins on my hands bulge blue from my increasing pulse. Every pore opens like a sinkhole. Miss Pratt tells me to lift my hands.

“Higher,” she says. Again and again, “Higher.” Until my hands are under her chin and her eyes cross to look at them. She does not touch them like she touched the other girls’ hands. On the other side of the room, Miss Avery stops her own inspection of little girl hands and watches Miss Pratt examine me. She watches with everyone else.

“And turn them,” Miss Pratt says, shaking her head the way Mama shakes her head over the starving Ethiopian children commercials. These children with their distended abdomens and hungry eyes, who are surrounded by gigantic flies as if they’ve already died. As I turn my open palms upward, my hands and arms balloon. All I want is to hide them. Or amputate them. My arms would just fall off and I’d run away and leave them behind. Instead I stand. I stand like that forever. I rotate my hands, palm up to palm down. I do this for each girl in the class. Miss Pratt directs them to all come and look. Palm up to palm down as they shuffle past and observe.

Miss Pratt gets her wand and whisper-speaks the way Gran does when words are too terrible to really say. She tells the girls what they already know. How unladylike my hands are. She taps the wand against her palm as if it’s all she can do to keep from striking me.

“This is what neglect looks like,” Miss Avery chimes in. “And my future debutantes of America, what does neglect say about a girl?” In unison the girls all answer. They say I have no self-confidence. “And what happens to girls without self-confidence?” Miss Avery asks. Nothing, the chorus answers. “Nothing,” they say. The collective “ing” drops from their mouths with a dull thud.

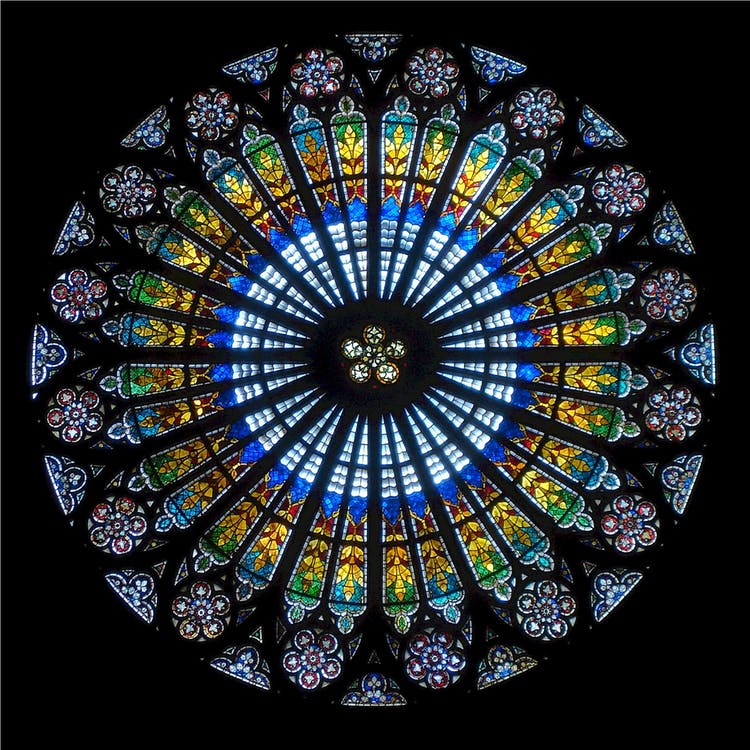

I’m sent to the vestibule to wait for Gran. Downstairs the other girls divide into pairs to trim, file, buff and polish each other. As they sit cross-legged amidst cotton balls and nail polish fumes, I sit on a wooden bench alone. It is hard and the tiny room cold. My breath comes out like the endless clouds of smoke Mama is always exhaling. I can see the street through the window. Through the clear glass below the stained glass angel. This angel who is fragmented by different shapes and colors, broken in the same way Picasso portrayed his subjects.

I am Joan of Arc. I am Saint Catherine of Alexandria.

There’s a dead squirrel in the road. Surrounded by a murder of crows that abandon it whenever a car comes along. I wonder why it’s a murder when the birds are crows and a flock when they are not. A flock for any other kind of bird. My hands are cold. I shove them back into my white gloves. To do this, I have to put aside the folded note for Gran. From Miss Pratt. Which I’ve already read. The note that says I’m not to come back until my hands are clean, smooth and properly moisturized. Not until her ragged, filthy nails have been manicured by a true professional. She tells Gran what a fine lady she knows her to be. Because of this, we know you’ll understand the importance of this request. She wishes in no way to offend Gran. After all, everyone knows what the situation is. She applauds Gran for all her efforts to better me. However, she writes, we simply cannot take Fiona back without a receipt to prove she’s been to a beautician. Furthermore, we encourage you to make the girl pay for it herself; doing so might guarantee a future of better hygiene.

The open sore is not mentioned. Undoubtedly, Miss Pratt found it too terrible even to acknowledge. She must’ve assumed that if I return, at least this one flaw will have the proper time to heal. To go away forever and never be seen or heard from again.

Outcast Fiona finds herself enrolled in a “Social Education” class; the class motto

is “teaching the art of sense and civility.” Ironically, the teacher and the participants are

anything but sensitive or civil, especially toward Fiona who is tortured by Miss Pratt and

Miss Avery no less than the medieval women who were strapped to the breaking wheel

and left for the ravens. Powerful and terse, with prose that makes the heart sing, this is a story so rich with innuendo and pathos that it changes with each re-reading.

—Kathi Appelt, 2012 Katherine Paterson Prize Judge

Sports brands | Women's Nike Air Max 270 trainers – Latest Releases