Derek Nikitas is the author of the only James Patterson book you’ll never read. The Murder of Stephen King was an installment of Patterson’s quick-paced BookShots series about a stalker terrorizing the eponymous author by re-enacting scares from King’s own novels. The novella was ready to publish in 2016 when Patterson, in an effort to avoid causing King any discomfort, canceled it. Thankfully, the next two novellas Nikitas wrote for BookShots have been published without any hitches. Diary of a Succubus was released earlier this year and You’ve Been Warned–Again, a horror story about a family Thanksgiving gone wrong, came out this October. If you’re noticing a pattern in the BookShot novellas you’d be right. Nikitas is a fan of thrillers and mysteries and authored three of his own suspenseful novels before he started writing for BookShots. Pyres, a crime thriller following three distinct women in the wake of a murder, was nominated for an Edgar Award for Best First Novel by an American Author; The Long Division, another thriller-bent novel about a long-lost mother and son reuniting and becoming caught in between a police deputy and a hunted killer’s endgame, was a Washington Post Book World Best Book of 2009. In addition to writing his own novels and for BookShots, Nikitas is an undergraduate advisor and assistant professor of creative writing at the University of Rhode Island, where he has had a hand in developing their new creative writing option.

Nikitas was one of my professors in my last year at URI, which I’d begun with no real plans for what I’d do once I graduated in the spring. I knew I was vaguely interested in creative writing, and I had some seedling notion that I’d apply to graduate school someday. Before taking Nikitas’ class my writing was directionless, but his boundless enthusiasm and support helped me realize my talents and eventually apply to the Vermont College of Fine Arts. Thinking back, it seems incredibly happenstantial that I emailed Nikitas earlier that summer to ask if I could join his already filled-to-capacity creative writing class—this probably makes it the most fortuitous coincidence of my life.

And now that I’m no longer in Rhode Island, Nikitas remains as supportive as ever: sending me well wishes, offering to read the stories I’m writing, and, of course, answering my interview questions.

The University of Rhode Island is establishing a new creative writing major—what are the goals of the new major, and did you have any role in shaping it?

So, it’s an “Option” within the English Major. The option is a way to give the students a sequence of courses culminating in a new creative writing capstone course. Our hope is that the Option will also tighten the sense of community and identity among writers on campus, increase English majors, and strengthen the college’s commitment to our department and our great activities, like the Ocean State Writing Conference, the Read/Write Series, the Ocean State Review and the Barrow Street press.

The department has long wanted this program, but it wasn’t feasible before I started my appointment. I wrote the specifics, with input from my colleagues, who had a long-gestating sense of what they wanted the Option to look like.

How do you manage all the different responsibilities in your life? From teaching to your duties as an undergrad advisor, to writing, and having a family.

I don’t always manage! Family and my own writing come first, and I try to write in the morning after the kids are in school, when the house is quiet, and before the work obligations creep into my mind. But still I live in a perpetual state of guilt that I should’ve written ten novels by now.

You’ve moved around quite a bit. You’re from New Hampshire but your education took you to North Carolina and Georgia, while you’ve taught in Kentucky and Rhode Island. Have the different environments/cultures affected how you write?

I just counted—I’ve moved twenty-five times in my life.

I feel like I’ve lived a good cross-section of American culture. I grew up a city kid with a single mother on government assistance for the first few years, visiting rural New Hampshire cousins and New England seaside upper-crust cousins. But I spent my teen years in the epitome of American suburban privilege, and have since lived in city and semi-rural environments. I’ve become a good chameleon, but when I think of “home,” nothing really comes to mind—or no one place does.

My first couple novels were rather focused on small-town Midwestern life and often highlighted the working poor. Getting my MFA in the South defined the way I wrote those early stories and novels. There’s a Southern ethos—the emphasis on regionalism, on hardscrabble lives, and “no nonsense” fiction that privileges scene and character above all else. Compare the narrative acrobatics of, say, Nabokov to the plainspoken, homespun style of Flannery O’Connor.

Since then I’ve been equally influenced by Yankees, who are prone to 19th Century-style austerity, and Europeans, who are prone to postmodern acrobatics. This is all horribly reductive, but not entirely false. I like to think I’ve learned to wear all those masks.

Do you have any special rituals you perform before you sit down to write?

Not really. I try to write at relatively the same time every day. When I’m really into a book, my goal is to get a rough draft down, or at least one third of the book, before I start revising. Otherwise I’ll obsess over language and never make any progress. I give myself a daily word count, just to push the book a little further. Usually around a thousand words. But during the brainstorming and revising phases, the process can be pretty haphazard. I’m pretty prone to writer’s block if I don’t have a solid plan, so these days I always have outlines to guide me.

You’re primarily known for writing crime thrillers. What draws you to the genre? What are the complexities of devising a “whodunnit” and revealing it to the reader in due time?

I’m interested in what drives people to bad behavior, the psychological element. I see crime stories on the news and that empathetic impulse kicks in: What emotional and mental conditions would have driven them to that behavior?

I’m interested in extreme mental states, how people think when they’re driven to the edge. These obsessions usually lend themselves to crime fiction, though sometimes horror and certain kinds of “weird fiction” as well.

I wouldn’t be the first to suggest that contemporary crime novels are the evolution of the so-called “social novels” of the 19th Century—the works of Dickens and Hardy and Eliot. Building a plot around a crime is a great way to explore a social tapestry, how characters from different social strata intersect and interact with each other across a highly structured narrative.

Honestly, the whodunit structure is probably the least interesting to me. I love intricate plotting and ironic turns, but the actual revelation of the bad guy at the end and the requisite uncovering of motive is often so perfunctory. If it somehow enlightens and deepens the characters, well, that’s all you can ask for, but that’s rare.

Take Dennis Lehane’s Mystic River. A classic crime novel, with beautiful evocations of character psychology and social tapestry. The least interesting thing about that book is who the killer turns out to be. On the other hand, his novel Gone Baby Gone is a stirring example of how to get it all right, including the reveal, because it’s so resonant.

Do you employ the same techniques when writing screenplays, or does the different format require a different approach?

I used to be much more improvisational with fiction because that’s how I was taught. But learning how to write scripts has made me a much more deliberate fiction writer as well. Now I can hardly write anything without mapping it out, scene by scene. Turns out, that’s my natural instinct, but I’d been resisting it for so many years because I was convinced it was somehow not “creative” or “intuitive.”

Even so, writing the rough draft of any piece of fiction, for me, is torturous and terribly slow because of the intense concentration on getting the language right. Language is vitally important in a script as well, but for some reason my script rough drafts tend to be comparatively breezy. It’s the careful molding of subsequent drafts that makes screenwriting a challenge.

Has writing for James Patterson’s BookShots taken any time away from your own personal projects? And if they haven’t, do you care to reveal what you’re working on right now?

I’ve written three BookShots (one of which will never be released!), and each of those books was necessarily written in a highly structured and disciplined three-month timeline. During that time, I was glad to avoid other projects.

Right now, I’m working on a couple scripts and a novel. The novel is a mystery set in “South County,” Rhode Island. It’s about a high school art teacher who becomes the focus of an investigation because she’s the only possible connection between two kidnapped students. It’s a “paranoia thriller” from her point of view. I’m trying to bring together my style and what I learned from Patterson—focused first-person narration, propulsive story, etc.

In an interview with The Providence Journal, you said Patterson comes up with the idea for a BookShots book and you flesh it out. Does being handed a set story hinder your creativity?

Just the opposite. I find parameters inspiring. I’m pretty scatter-brained, so it’s hard for me to focus on a totally blank canvas. But rules create focus, and that smaller area of concentration generates ideas much more readily.

Sure, the Patterson BookShots gave me parameters like I’ve never had before. Were there times I wished for more autonomy? Yes, but I had to remember I was writing for a reason beyond my own “vision.” I was writing to a readership much larger than anything I could’ve otherwise reached. So I had an obligation to Patterson and his readers to meet challenges within their expectations. In the end, I think it has made me a more flexible and less self-involved writer.

What are you reading right now and what’s the last great book you read?

Two fantastic books I’ve read this year are Dodgers by Bill Beverly and Eileen by Otessa Moshfegh. Right now, I’m reading a whole lot of student fiction and re-reading classic short stories in preparation for class.

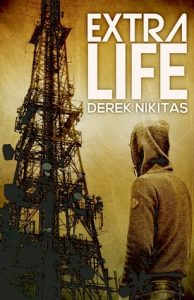

Nikita’s most recent novel, Extra Life, was published in 2015 with Polis Books.