Hunger Mountain editor Bethany Hegedus is the author of Grandfather Gandhi, a new picture book she co-authored with Arun Gandhi, grandson of Mahatma Gandhi. The book, released in March 2014 by Atheneum Books for Young Readers, was illustrated by Evan Turk. Here, with an introduction by Matthew Winner, Bethany interviews Evan about his picture book debut.

Matthew Winner: When I first held a printed copy of Grandfather Gandhi in my hands, I knew I had something special. The collage work and intricacy of the illustrations were immediately affecting, and the textures represented in the art gave the story a physical grounding in the landscape and people of India and to the community at Sevagram. I later had the opportunity to speak with Evan Turk, alongside Grandfather Gandhi authors Bethany Hegedus and Arun Ghandi, on a panel during the book launch at Books of Wonder in New York City. It was immediately clear that the reverence of the book’s source material resonated deeply within the hearts and minds of its creators. But what was more evident to me was that the individuals behind Grandfather Gandhi were something special. If his debut in picture books is any indication, Evan Turk’s evocative artwork will have far-reaching effects in children’s literature. In the interview that follows, Turk candidly describes his process from concept to his careful selection of materials to the message in the story’s text that he worked to communicate through the art. It’s an opportunity to discover anew the story of Grandfather Gandhi and to lose yourself in the world preserved in Turk’s art. Wonder and enjoy.

[doptg id=”2″]

Bethany Hegedus: As this is your picture book debut can you walk us through the process of being chosen as the illustrator for Grandfather Gandhi?

Evan Turk: It was my senior year at Parsons and we each had been working on a senior project. I was working on an animation and children’s book of a story that I’d written about a little boy in India. We each gave three-minute presentations to a panel of professionals from the industry, and they gave us feedback on our work. One of the people on my panel happened to be Ann Bobco, art director for Atheneum/Simon & Schuster. While I was taking questions at the end, she raised her hand to her ear and gave me the “call me” sign. We set up a meeting, and I came in to talk with her and the editor, Namrata Tripathi, to show them my work. Afterwards Namrata asked me if I’d be interested in seeing the manuscript for Grandfather Gandhi and doing some samples, so naturally I freaked out a little bit, called everyone I knew, and then replied yes.

BH: Once the manuscript was assigned to you, how did you get a feel for the setting? Did you enter the story with much historical background or did you need to immerse yourself in research about life on Sevagram? Where did you begin? And how did that entry point change or shift as you worked?

ET: Other than one Indian history course and a family trip to southern India, I didn’t have too much background when I started doing the samples. I began reading biographies and watching movies, and trying to get a feeling for Gandhi’s philosophies and how they shaped the ashram, while using historical photographs of Sevagram for reference. As I moved on to the final art, the 1982 film Gandhi was actually very helpful in terms of actually getting to see Sevagram and see the body language of the people moving and working around it.

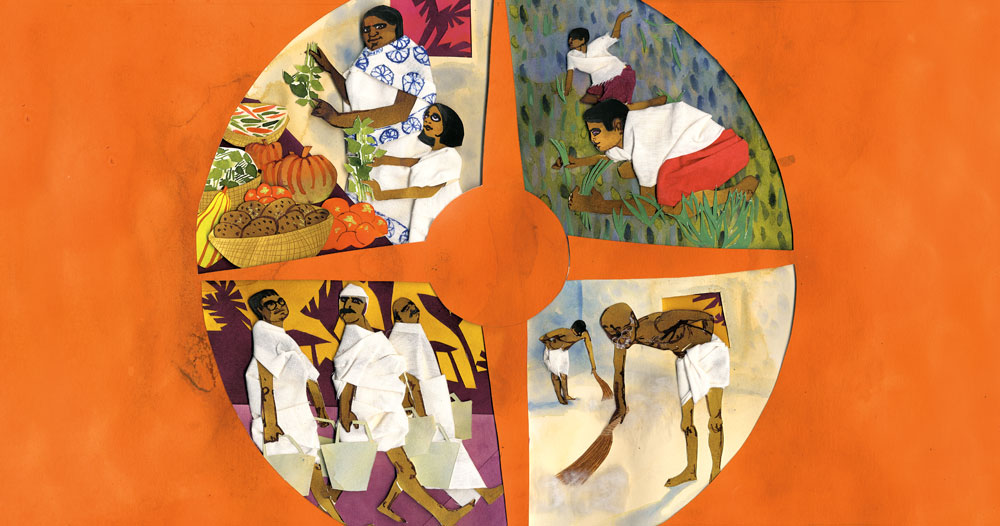

BH: The final art of Grandfather Gandhi, a combination of watercolor, paper collage, cotton fabric, cotton, yarn, gouache, pencil, tea, and tin foil, is stunning and is more than the sum of its parts. There is even a notation in the book that says the cotton was hand spun on an Indian book charkha by Eileen Hallman. How important were all these details to you and what do you hope the finished images for the book convey?

ET: The look of the illustrations definitely evolved as I made them. I like to be able to be spontaneous while I’m working on something, so I went with whatever felt right to me in the moment. When I look at Indian art, there are so many different layers of patterns and shapes, so the physical layering of shapes in collage lent itself to the content.

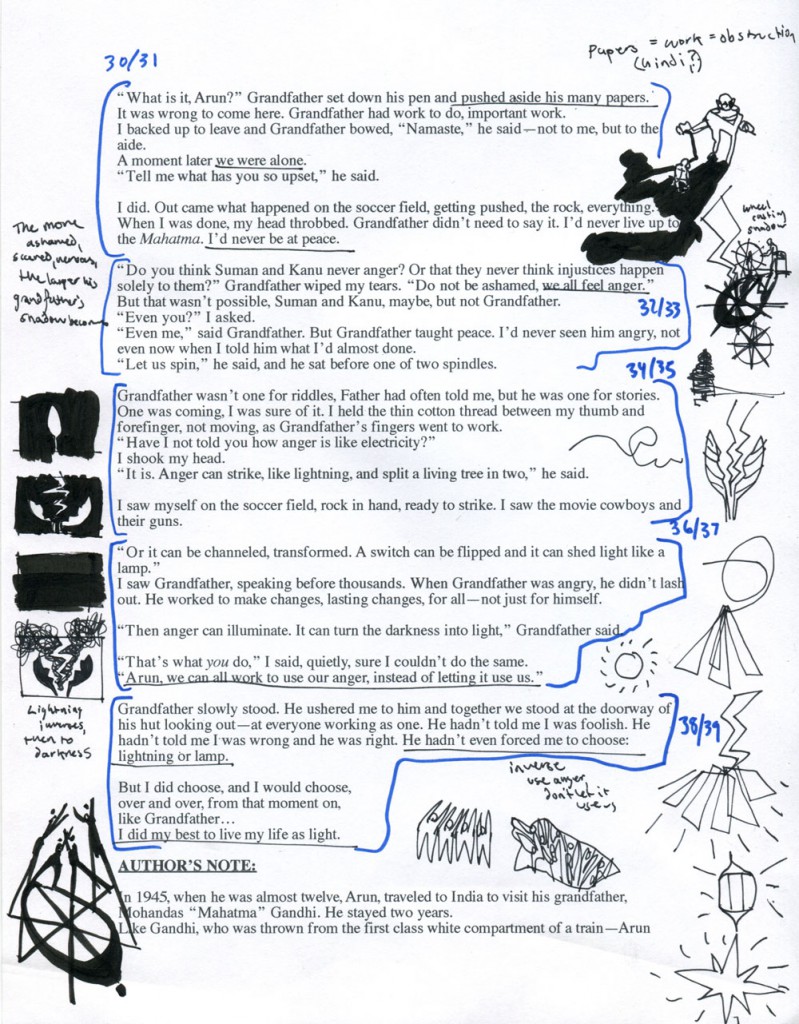

For the yarn, I thought that the idea of spinning raw, unruly cotton fibers into yarn was a beautiful metaphor for Arun learning to channel his anger, so I wanted that to be a part of the illustrations. I had a very romantic notion that I was going to spin all of the yarn by hand, it was going to teach me self-discipline like it did for Arun in the story, and it would be this very meditative process that would happen as I was doing the book. So I bought a charkha and a box of cotton shipped from India and I planned to sit down every day I worked on the book and try and spin some thread for an hour or so. I did that for a couple of months, trying a few days a week to spin anything at all. But it was very difficult, a lot harder than I was expecting, and after two months I had made maybe two inches of lumpy thread. The book was due in two weeks and I began thinking it was time to find some other options. While looking online for somewhere that I could buy charkha-spun yarn, I found Eileen’s website (http://www.charkha.biz). She had how-to videos, which I probably should have had a couple months ago, but I called her and asked if I could buy some yarn spun on a charkha. She said she didn’t really sell it, but said, “Oh of course, I can just spin some for you.” I asked, “Oh wow, how long is that going to take?” and she said, “Oh, about, five minutes.” So when she was able to do in five minutes what I had been trying weeks to do, I was thrilled, and I think her beautifully spun yarn made a nice contrast to my lumpy mushes of cotton in the book.

BH: How did you strike a balance between keeping the art sophisticated yet child-friendly?

ET: I think art that communicates to adults will communicate with children as well. The story is actually very heartfelt and emotional, so it was important to me for it to have that feeling and gravity. But it’s also the story of a little boy, and I wanted to illustrate it from that point of view, so I think that adds a level of playfulness and theatrics in the art.

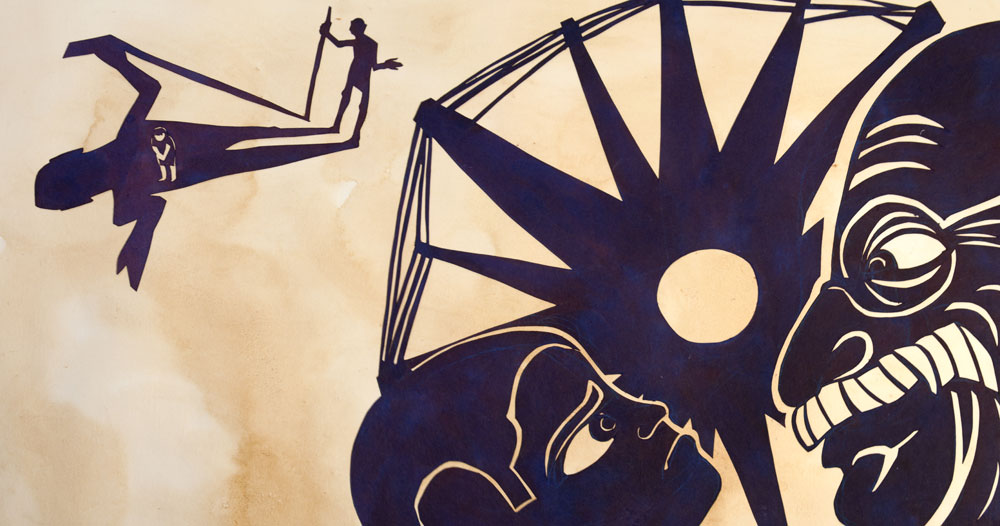

BH: As the authors, Arun Gandhi and I we were especially pleased to see how the theme of inner and outer shadows and lightness vs darkness that the text deals with came into play in the art. The palette ranges from bright, vibrant hues reminiscent of the Indian sky and culture to one spread that is starkly black and white. How much was this intentional? And, if intentional how did you keep this aspect from overpowering other symbols in the book—such as the spinning wheel?

ET: Most of the story is about how Arun is feeling about what’s happening, and about how he’s internalizing it, so I wanted that to take center stage in the illustrations as well. A lot of it came out of a little thumbnail I did on the original manuscript of Arun standing in Gandhi’s shadow, which is such a big part of the story, so I used the idea of shadows to communicate how Arun is feeling internally. In Indian art and textiles the colors are vibrant and vivid, which works as a perfect contrast to the shadows, so I think that struck a good visual balance and reflected on Arun’s decision about whether to live his life as light from the end of the book. The shadows also helped to tie all the other symbols, like the spinning wheel, together, because everything casts a shadow, and shadows have a way of weaving everything together into a single shape.

BH: Did you have any fears or trepidations depicting Gandhi on the page in a new, and very human form, as he is a figure many have expectations of and revere? If so, what were they and how did you overcome them? What was it like to hear Arun Gandhi’s response to the work: “The book has taken a beautiful form.”

ET: I think I was most nervous when I was doing the samples for the manuscript before I had been given the contract, because I knew it was going to be reviewed by Arun. For me, it was a little intimidating to depict someone’s grandfather, famous or not. It’s such a personal connection, and you want to be able to capture something about how that person felt, and of course I never met him. But you hope that someone who did know him is going to see something of that person in what you draw. I think it also gave me a degree of freedom, because the whole book is about how Gandhi wasn’t a perfect saint. He was a real person, and that gave me some freedom to draw him in a way that wasn’t perfect or reverent; he could just be a loving, caring, grandfather.

Hearing Arun’s response to the book, especially after meeting him and hearing him talk about the art in interviews, was so wonderful for me. I learned that there is a different kind of pressure illustrating someone else’s text, because you want them to respond to what you’ve created with their words. As you told me, Arun is a man of few words, but to hear that he felt that the illustrations “put life into the book,” since ultimately it’s his life I’ve been illustrating, really touched me.

BH: In spending some time on your website, I know you travel and have an interest in cultures outside your own. How do you merge your own artistic voice with the art of the time/place you’re representing? What elements of the design are grounded in African art and which are yours? Where did this interest in exploring culture through illustration come from?

ET: I’ve always had an interest in travel and other cultures, and when I started doing illustration I found it was an entry point for me to be able to connect with other people and places on a deeper level and really try to understand them. When you’re looking at art from another culture, and trying to figure out why they create art in the way that they do, you really can learn a lot about their philosophy. I love looking at art from all over the world because it is often art that was created before things became so global, so people arrived at ways of looking at the world that are so completely different, but still related. When you try to make art with that philosophy in mind, it allows you to look at something in a completely new way, which is something in illustration that is always exciting for me.

I think that in terms of merging my own voice with different art styles and cultures, I think it’s something that just happens naturally. Hopefully, the more I understand a culture, the more their philosophy comes out in the art. It’s not really a conscious balance, because whatever I draw, it’s going to end up looking like I drew it, so as long as I’m trying to learn, the balancing takes care of itself. In many types of African art in particular, there is a vibrancy, pattern, and freedom to exaggerate that I always respond to, and I think these have become a part of my own taste and design.

BH: What is next for you—in children’s books—or otherwise?

ET: I have a few animation and illustration projects in the works, but one in particular is a children’s book I’m working on about the art of Moroccan storytelling, and how stories are what create culture and give people hope. There is a thousand year old tradition of public storytelling in Morocco, where religious stories and folktales are passed down through generations, and each storyteller becomes a library of thousands of tales. But as the storytellers have gotten older without apprentices, the tradition is dying out. I wanted to make a story that talks about the importance of this kind of storytelling, not just for Morocco, but all over the world. The book is about how storytelling created Morocco, sustained it through generations, and ultimately, with the help of a young apprentice storyteller, what saves it from the desert in the end.

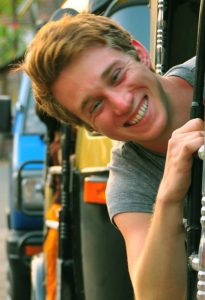

Evan Turk is an author, illustrator, and animator working in New York City. He is originally from Colorado, and loves being in nature, traveling, and learning about other cultures through drawing. He is a graduate of Parsons and continues his studies as a member of Dalvero Academy. Visit him at evanturk.com.

Matthew Winner is the author of the Busy Librarian blog and host of Let’s Get Busy, a weekly children’s literature podcast with authors, illustrators, kidlit notables, and everyone in between.