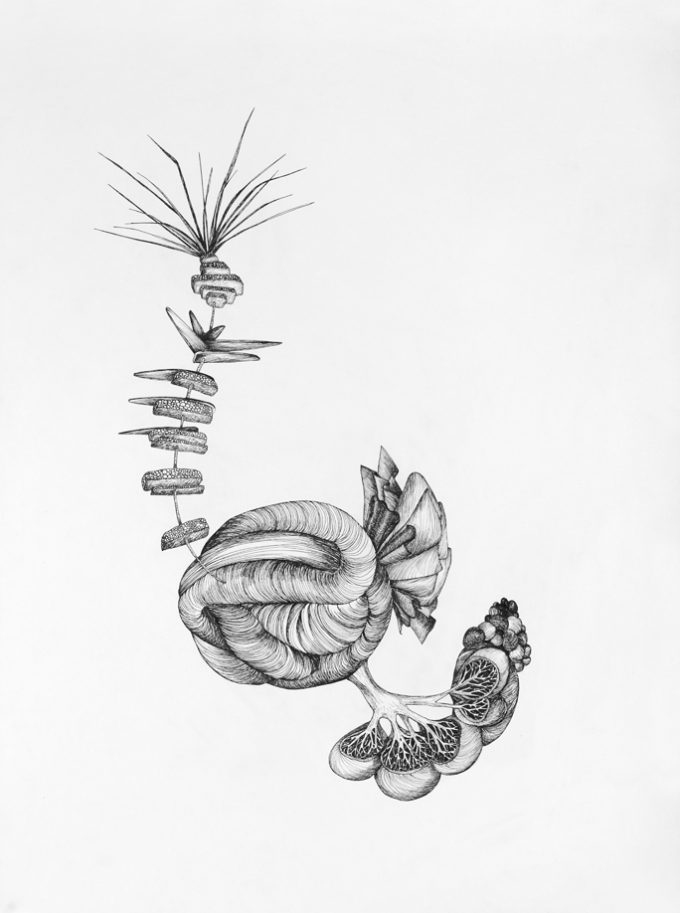

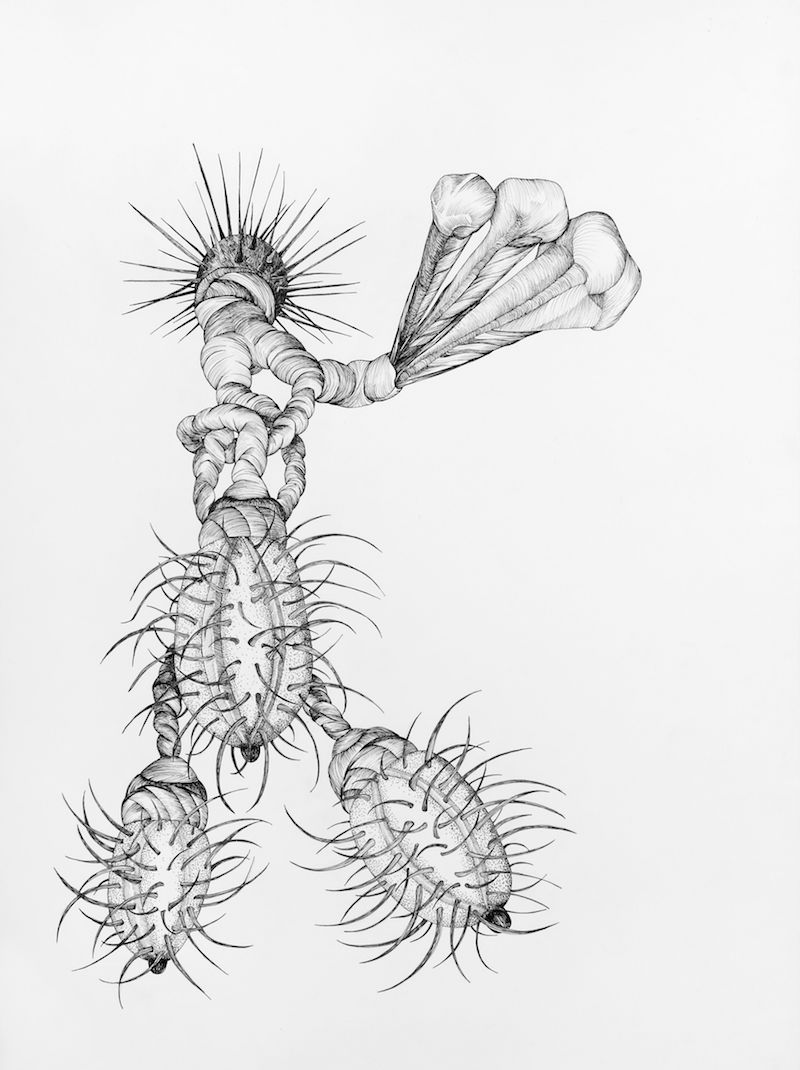

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#372a55′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”] Teczotchicin Vine The vine’s voraciousness dwarfs even the kudzu of the Southern United States, whose growth of one foot per day is a snail’s pace compared to the Teczotchicin’s rate of up to twenty-five meters. It’s one of the rare… Continue reading Invasive Species & Their Habitats

Alexander Weinstein