[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#33999′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

My father sits at the kitchen table with his shoulders hunched, staring at a feather cupped in his rough carpenter’s hands. Its barbs are clean and white. The table is bare except for the wooden box still encrusted with dirt. It has no latch, no key. My mother had to bash it open.

The kitchen is cold, and there is no dinner. Seventh grade ended today, so there is no homework. We sit across from each other in silence. I’m often restless, though I try not to be. “Young ladies should not fidget,” my father always says. I will never be a lady.

I try not to fidget tonight, and even sit up straight. There is dirt under my fingernails. I hide my hands in my lap so my father won’t see, but he has forgotten I’m here. He just stares at the feather and doesn’t say goodnight when I go upstairs, my stomach growling.

In my room, there is a feather on my pillow. It glows white in the dark; the special kind of dark that makes you worry you’ve gone blind. When I was little and still afraid, my mother would lie with me, telling me story after story. Little girls who fell in love turned into sea foam or wind. They walked as if on knives, kept silent for seven years, wove thistle shirts until their fingers bled. They never learned to leave locked doors alone. Hunters and thieves and kings pursued them, carved out their hearts, scooped out their eyes, and snipped off their tongues. She told her own story like a fairy tale.

I do not brush my teeth tonight, since she is not here to make me. I cannot hear my father. Maybe he has fallen asleep at the kitchen table. The only sound is the house groaning as it settles.

My father built this house with his own hands. He learned to build from his father, who learned from his father, who made whaling ships. People came from miles around to watch my great-grandfather erect giant ribcages on the shore. He sliced the trees into wide planks and laid them side-by-side. He ran rope between the boards so when they swelled with water, they wouldn’t crack.

My father makes houses like boats, with wood and rope. He built our house for my mother over the pond where they met. He filled the pond with stones, a foundation for their love.

#

There are scraping noises below my window. It is still dark, but I can just make out my father at the edge of the yard by the woods. He digs up the grass from the back door to the edge of the forest. He digs until our yard is a pit of stones surrounded by mountains of dirt.

My father thrusts his shovel under each stone and leans on the handle, so hard it creaks. Finally, the stone sighs a puff of dirt and my father picks it up, bending his knees and keeping his back straight the way we learned how to lift weights in gym class. It was the only useful thing I learned in gym class. He heaves the stones to the side along the tree line until they make a wall around the hole.

My father does not eat the sandwich I make for him. When I ask what he’s doing, he just shakes his head, so I do not ask again. He doesn’t seem to remember that he signed me up for ballet this summer, and I am not going to remind him. I pack my compass and canteen, and slip into the woods.

My mother used to send me searching for what she called “objects of unexpected beauty,” as though she didn’t expect me to find beauty in Stone. But it is here, in the wide fields with crisscrossing stone walls—and the stones themselves. They seem so plain at first, but upon closer inspection, there are threads of quartz glimmering through the granite. It’s true that there’s only so much to Stone, but I have walked the perimeter exactly two hundred and ninety-nine times and I’ve discovered something new on every journey.

I used to bring my treasures to my mother—a stuffed bear with one eye, an hourglass with no sand. In the beginning, she pretended to admire my treasures, but as time passed, she stopped looking, until I no longer brought her anything. The box was different. When I offered it to my mother, her hands shook.

My mother said girls have to take care of themselves. That’s how we avoid turning into sea foam and falling down wells. That’s how we escape hunters and kings who chop and carve and snip and steal. That’s why I practice punching every afternoon.

I got my boxing pad from Old Bob Brick, who works at the deli counter. The veins on the backs of his hands bulge like roots. He was a boxer, and his knuckles are calloused from breaking noses. I like to stare at them while he carefully slices the deli meat. One day, I will have hands like his.

There is a nail on the side of the house where I can hang my pad at punching level. The ground is eroded at the base of the wall here, like gums worn away at a tooth’s root. The box was wedged between two exposed foundation stones.

I do one hundred punches on one side, then a hundred more on the other. The first few weeks of training, my arms ached after twenty punches. Then fifty. Then seventy-five. Now I have calluses on the first two knuckles of each hand.

My father does not like the calluses. He says my bones are still growing. He does not understand that I have to take care of myself. “That’s my job,” he says, while he combs the tangles from my hair.

He has not combed my hair since the night before last, and the tangles may never come out. He has been digging without rest. His palms are blistered and bleeding. He’s tired, but he is not weak. When David Redd pushed me into the deep end and I couldn’t make it to the edge, my father dragged me out. He threatened to kill David if he ever touched me again. David tripped me in gym the next day, but I didn’t tell my father. I just punched him in the stomach, and he hasn’t bothered me since.

When my knuckles are sore, I make my three-hundredth journey around Stone. It feels like time should have stopped when my mother left, but the town continues without us. People go about their lives, shopping for groceries and discussing car repairs in loud voices. The sidewalks and shop windows are too bright, as if it’s just rained.

I return to the dirt and the stone walls and my father’s silence. I help dig.

Digging is useful. I can feel my muscles tearing and reknitting stronger than before. I pretend I’m searching for treasure. I find a trove of shells that gleam in the sun. I find a skeleton with wing bones folded tight around a hollow heart space. The swan’s long notched neck is graceful even in death.

My father won’t let me keep it. He lifts it with his shovel and deposits it gently in the woods.

#

When the wall of stones has reached my waist, my father pries up a rock, and the earth below it becomes wet, the way blood wells up after a tooth is pulled. He shouts, and I drop my shovel. He spins me in circles, slipping in the mud. He has never had trouble lifting me before. His eyes are wide and his mouth is open as if he might laugh.

He digs with renewed purpose, though he will not say why. Blood runs down the shovel handle. I help him dig into the damp space, and by evening, a pocket of what used to be our backyard is filled with water.

My father is still digging when I go up to bed without brushing my teeth. I haven’t brushed them in three days, since my mother left. I lie on top of the sheets, guarding my treasures. It is too hot to sleep, and the shovel scrapes below my window.

Sometimes, when my mother did not feel like telling stories, she would ask what I wanted to be when I grow up. An archaeologist. Geologist. Anthropologist. “What else?” she asked. Architect. Historian. “What else?”

She would lament that she had never accomplished anything, except having me. She wanted to be an artist, but had nothing to paint. My father suggested art classes at the community college, but the house would fall apart without her, she said.

She’d lie in bed beside me in the dark, and as she drew one finger between my eyes, she’d say, “You’re the best thing in my life.”

#

My father is asleep on the steps with his head resting against the house. His legs are outstretched, his feet submerged in the pond that has conquered our backyard. His face is tipped to the sun. His nose is peeling, and his cheeks are shadowed with stubble. When I sit beside him, he drags his eyes open, as if they are made of iron.

“Now she’ll come home.” His voice is rusty.

My father knows better than that. He knows my mother’s stories as well as I do. One task is not enough to win her back. He must move a mountain with a silver spoon. Or plant an orchard in a single day. And when he finally finds my mother, he must keep his arms around her, even when she turns into a viper or fire or cloud of wasps. He must prove he deserves her.

The totems that help a hero along a magical quest are as elusive as breadcrumbs. Knotholes disguise entries to other worlds. Wooden shoes take the hero bounding across the ocean. I keep my powers of observation sharp so I won’t miss something and end up spitting toads.

Armed with my compass and canteen, and my mother’s feather in the pouch around my neck, I scour the woods for enchantments. While my father is resting, I will discover the next task. It’s my fault she left, after all.

I’m concentrating so hard I trip over the swan skeleton tangled in a nest of vines. Its neck bones have tumbled into a heap. They are smooth, as if worn by waves. I arrange them like a puzzle, except for the one I slip into the pouch with the feather.

A pebble glances off the top of my head, and a boy laughs in the branches. Though he is very high, I can see that when he laughs, the corners of his eyes crinkle.

“Who are you?” he calls down to me.

“Alex.”

“That’s a boy’s name.”

“No, it isn’t. It’s short for Alexandra.”

He looks at me thoughtfully, without blinking.

“I’m Amir,” he says. “You can come up, if you want.”

I don’t need his permission, but I’m good at climbing trees. I know just where to put my feet. And a tree is almost as good as a roof for searching out secrets. The light sifts through the branches as though I’m underwater, climbing toward the sun.

Amir slides back on his branch to let me sit beside him.

“Most girls can’t climb that well,” he says.

His voice rises and falls. I know all about how boys’ voices fly out of their control, which must be embarrassing.

“They could if they trained.”

He raises one eyebrow, as if he’s practiced in front of the mirror.

I can see everything from here: my father’s pond, my father on the steps, the road running out to the highway. I can see all the secrets in a town that says it has no secrets.

“Did you hear about the bear bullet?” Amir asks. “Last week on I-90, two cars were driving from opposite directions, both going about eighty miles an hour—”

“Is this a math problem?” It’s rude to interrupt, but I don’t like math. I don’t like questions about two trains coming from opposite directions and what time they would reach the station. In the real world, you’d just check the train schedule.

“Two cars were coming from opposite directions,” he says, as if he hadn’t heard me, “and a bear came loping out of the woods. One car hit it—whack!—and sent it flying like a bullet right through the windshield of the other car.” He slams his palms together. “A bear bullet.”

“Was the bear okay?”

“Of course not.”

His smugness is annoying, but my father says it’s not polite for a young lady to point out other people’s faults, especially when she has so many of her own.

“Have I disturbed you?” He looks a little nervous, as if I might cry. So I tell him one of my mother’s stories, about the Marsh King who dragged a maiden down into the deep, black mud to be his bride.

A smile cracks across his face. He unwinds a rope from the trunk, and a basket descends from the branches. He is well fortified. There are other ropes leading to a box of cookies, a flashlight, a bucket of rocks he calls missiles. He even has a net to trap intruders. He says I am lucky he didn’t use his net on me because he made it himself and it’s strong enough to capture a full-grown man. He could live up here, if he had to.

Across the pond, my father stands and steadies himself against the house. His ribs poke through his shirt. He rubs his eyes with the heels of his palms like a little boy, but no one would dare to pity him.

“What’s wrong with him?” Amir asks, his eyes gentle with concern, as if he pities me.

“Nothing’s wrong with him.” I have my father’s temper. My eyes bug out and a vein in my forehead twitches like a worm on a hook. Sometimes, I make myself mad on purpose, just to watch my face change.

“We’re on a quest, and you’re wasting my time.” I shove back on the branch so fast I upset one of his baskets, and missiles rain to the ground. Amir grabs my wrist.

“I’m sorry,” he says, his voice soaring out of reach. “If you tell me about it, I can help. I can teach you to make nets and launch missiles.”

His fingers are hot. His eyes are blue. My mother warned me not to trust boys; they will take what they want without asking. But Amir can’t take anything from me. I have calluses on my knuckles and scabs on my knees. I’ve made it to one hundred and ten punches without getting tired.

“I don’t need help.” I leap from the tree in a single bound.

#

How My Parents Met, my father’s story:

He was putting a roof on Old Bob Brick’s house. You can see everything from a roof, like how the forest around Stone goes on forever. You can see all the secrets in a town that says it has no secrets.

From the roofs of Stone, my father saw Mrs. Milne the librarian kissing Mrs. Fuste the pharmacist behind the grocery store. He saw Millie Rosewood sneak a cigar out of Old Bob Brick’s pocket while he napped in his backyard. He saw Marcus White’s fiancée break his heart, and he saw Marcus walk into the woods without a compass or a canteen. My father watched and watched, but Marcus never returned.

My father saw many other fascinating things—but by far, the most fascinating was my mother. He was sitting on the roof, eating his supper and looking for secrets, when he saw her, bathing in the pond.

My father stole through the trees to the water’s edge. My mother had left her dress on the ground, and he picked it up so it wouldn’t get wet. He stood there, holding my mother’s dress.

He says she wasn’t embarrassed. She waded from the pond and held out her hand. And that is how my parents met.

How My Parents Met, my mother’s story:

She would say nothing, only sigh.

#

My stomach groans in my sleep. The house groans too, shuddering away from the water that laps at its sides. A film is closing over my father’s pond, and mosquitoes hum above it like a storm cloud. My father waits on the back steps. He waits for the king of the birds, or the wise fish, or the wind. He waits for someone to tell him what’s next.

He doesn’t answer when I ask why he’s not eating his sandwich. He just stands in the shadow of the house, staring at the pond. Maybe he has sold his voice to the sea witch, or taken a vow of silence.

He has deep wells below his eyes. I wrap my arms around his waist like I did when I was little. The mosquitoes whine above the pond. My father’s heart beats against my cheek. I used to find his hug reassuring.

He breaks free of my arms and staggers inside as if he has never walked before. The hallway light gleams off his scalp where his dark hair is wearing away. At the end of the hall behind the staircase, he shifts aside the chair that guards my mother’s studio. It was a storage room until one day he covered my mother’s eyes and led her inside. He’d exchanged the boxes and cleaning supplies for a couch and an easel with a fresh canvas. He’d hung her favorite picture on the wall. In it, a woman stands at a window with her hips cocked, one foot tipped behind her. Her hair is tousled like she just woke up. All you can see out the window is water, as if the house is floating on the ocean.

My mother flung her arms around my father’s neck, her dark hair falling loose. My father dipped his hands into it, as she looked up at him, smiling. I remember that smile because I saw it so rarely—when I asked for another bedtime story, when I brought her my first treasure.

My father closes the door behind him. The flies circle his uneaten sandwich. I should have kept my arms around him.

I won’t let the house fall apart. I wash my father’s dish and sweep the dirt from the doorway. There is nothing left to do, and yet my mother was always harried. She washed the dishes and the laundry, and when the dishes and the laundry were finished, she mopped the floor. By the time the floor was dry, there was more laundry, and then dinner and more dishes. Endless chores kept her from leaving the house, until her skin was so pale her veins shone through it like rivers.

A plank jumps beneath my feet. A moan shakes the foundation. The floorboards ripple from wall to wall, but the straining ropes hold them in place as they crack like knuckles. I press my eye to a knothole. Water glimmers below the floorboards. The spark of golden fish. The Marsh King’s milky eyes glowing in the gloom. A knock so loud I thump my forehead on the floor.

It’s just Amir on the front steps. He holds out a bag of powdered donuts and asks if I’ll teach him how to punch. The Marsh King moans deep under the house.

#

Amir’s fingers are long and narrow, and his nails are bitten down. My hands are not as quick—but they are stronger. He admires my calluses, and I teach him to keep his thumb folded over his knuckles as he punches. He leaves streaks of blood on my punching pad. When sweat runs into his eyes, he asks me to tie a bandana around his forehead. My fingers fumble in his hair as I pull the knot tight.

While my father sews robes from thistles or spins flax into gold, Amir and I collect missiles. He shows me how to weave a net that can capture a full-grown man. He doesn’t tease me like the boys at school, or tell me I don’t act like a girl. He doesn’t care that I haven’t brushed my teeth in days. And he is a good audience for my mother’s stories. He likes their darkness, full of wind and stolen voices.

Amir has heard the same stories—except the versions he knows have been milked of their poison. They have cartoon villains and happy endings. He likes mine better, he says, while his fi ngers knot the twine. In my mother’s stories, the monsters are real.

The trunk warms my back. The branch grazes my thighs. My legs hang in the hot air as Amir pulls a picnic basket up through the branches. Sandwiches and lemonade and chocolate chip cookies. He smells like chalk on hot pavement.

“Do you believe in monsters?” he asks. His hands tighten on the rope. Our picnic swings in the sun.

“Of course.”

“The Marsh King and the troll at the bridge, Rumpelstiltskin and the Undertoad—they’re all the same,” he says.

“I guess they could be.”

When I close my eyes, the sun glows through my eyelids. I practice heightening my other senses. The hairs on my arms lift as the wind swings to the east. I feel the warmth of Amir’s legs, so close to mine but not quite touching. If I listen hard enough, I might hear what the wind is saying.

“I’ve seen him,” Amir says, hugging the branch with his knees as if afraid he’ll fall.

“Who?”

“The Marsh King. He’s as big as a bull and covered in warts. He eats children and pets, and his mouth is so wide he could swallow you whole. He waits below your bed, and under the stairs, and in the pool to drag you down by the ankles. And he’s not always hiding. Sometimes, he’ll sit at the kitchen table with a newspaper. Or wait in the truck, listening to the radio. He could be anywhere.”

He weighs a missile in his palm.

The missiles are chunks of granite mottled with quartz. I slip one into my pouch with the feather and the bone. It knocks heavy against my chest.

I let him hold the feather, burning white against his sun-dark hands. He strokes the barbs with his fingertip so they separate and reseal in a neat row. He listens as I tell him the one story I’ve held back, the one that bound my mother to Stone, to my father and me.

Amir spins the feather between his fingertips. He is silent so long I wish I hadn’t said anything. Then he tucks the feather behind my ear.

#

Cracks spider up the walls. The Marsh King’s milky eyes glow beneath the floorboards. He will not answer my questions.

Amir and I search for entrances to other worlds and the wooden shoes that take the hero bounding across the ocean. We trace the same old paths through the woods and collect missiles and weave nets, but nothing happens.

We wait on the back steps for the king of the birds, or the wise fish, or the wind. I don’t know what’s next. The day is empty and heavy. Amir stirs the water with his toes, sending sluggish ripples against the house. My knee sweats where it presses against his, and our feet are ghostlike beneath the water. A mosquito alights on my wrist. Amir brushes it away, and the pressure of his fingers remains long after his touch.

The studio door is locked. I press my ear to the wood, and though I can’t hear my father, I know he is still hard at work. But he needs to act faster. Soon, she will forget us.

#

The darkness is so thick my eyes ache. My bed skates across the floorboards. My pictures tip off the walls as the house keels like a ship on a rough sea.

The water ripples from my steps in oily rings. Here, at the spot where I found my mother’s box, the house rises off its foundation. The pond has reclaimed the land beneath it. Between the house and the pond there is a sliver of space like a cavern at low tide. All this time, I’ve been peering into knotholes, while this must be the entrance to my mother’s world. The cavern is just high enough for me to crawl inside.

“What are you doing?” Amir kneels beside me. He peers under the house, the planes of his shoulder blades lifting beneath his shirt. The mosquitoes swarm around us. The water soaks up my legs as I crawl into the cavern.

Amir grabs me around the waist. My shirt rides up, and his hands skid across the bare skin of my hips.

“Please.” His fingers hook onto my hipbones. Everything rocks above me, open and ravaged. My mother warned me.

“Let’s do something else,” Amir says. “Something normal. We could go to a movie.”

“No.” Like knuckles on a punching pad. That’s how it starts: movie, then house and child, laundry and dishes and more laundry. Amir releases my waist.

The pond is black and still as pavement. I almost apologize, but I’m not sure I should be sorry.

“I saw her,” he says. His voice is thick, as if he’s struggling against a spell compelling him to spit words like toads. “I was in the tree and I saw her, days ago. She came out of the house with a suitcase and got into a car on the corner, and she drove away. Your mother left, and you know it. Grow up, Alex.”

A cloud of mosquitoes lifts around him as he splashes away, and I kneel in the greasy pond until he is gone.

A moan ripples through the water, more a vibration than a sound. The Marsh King crouches below the house. His milky eyes glow in the gloom. His hide quivers with anticipation. He could swallow me whole.

#

My father does not answer my knock. The key to my mother’s room still hangs on the kitchen hook. When I open the door, dust sifts through the air and settles over him. He is lying on my mother’s couch with his face to the wall. The curtains are drawn. He does not move an inch. He does not make a sound. I hold my breath, afraid he might be dead, but I can just barely hear him breathing. The easel stands empty in the corner. My mother never bought paint.

There are no thistle shirts, no skeins of gold, no boots that take the hero bounding across the sea. There is nothing except a sad man in a quiet room. All this time, my mother has been waiting, while my father has been lying here. And instead of helping, I was playing with a boy.

The blood rushes in my ears. The vein in my forehead throbs. I press my hands against his back. He does not turn away from the wall.

“What about the quest?”

My voice hangs empty in the air.

#

In my mother’s stories, the maiden sinks through the swamp, through the ceiling of a crystal palace where toad servants clothe her in silken gowns. She tumbles down a well into a golden forest. She walks for seven days that feel like seven minutes. Oceans peel back like orange rinds. Her dress always stays clean.

The ground slopes and the water deepens. I am not afraid. I have calluses on my knuckles and scabs on my knees. I’ve made it to one hundred and twenty punches without getting tired. I have trained for this.

The ground drops away beneath my feet. It’s so dark I can’t tell whether my eyes are open or closed. The water slides against my lips. My legs tingle with the brush of darting fish. Moss seeps from the house’s belly, and the water trapped here is sluggish. Wood rasps the top of my head. The water is rising—or the house is sinking.

One last gasp of air, and then nothing but the weight of water on all sides. I hold my breath, pushing through the quiet and the cold. Oily bubbles erupt against my cheeks. Though I kick, I’m no longer sure I’m moving, and there’s no space to turn around. My lungs ache. No one knows I’m here.

The treasure pouch knocks against my chest. I fumble at the swollen knot. The feather, the missile—the bone. I put the bone between my lips, and air trickles into my throat.

Moans swell around me like whale calls. The Marsh King crouches below, milky eyes glowing in the gloom, greasy hide quivering with anticipation. His talons dig into my ankle, and he yanks me down, tearing at my legs. He spins me like an alligator rolls its prey. My head slams the underside of the house. Colors burst behind my eyes. I grip the bone between my teeth and wrestle Amir’s missile from the pouch.

I draw my knees to my chest, making myself small, and smash the missile hard between my feet. A groan thrums through my bones. The shock of it jumps in my eyes like tears, and the grip on my ankle loosens. I strike again and again, turning the water coppery, kicking until his grip releases. His groans thunder through my stomach. Water pours up my nose, burning my throat. My heart drums in my ears. My knees scrape stone.

The ground slants upward. The water lowers, and I breathe deeply again, emerging onto the bank of a lake surrounded by pines as tall as masts. Stars peer through branches. The night smells like pine, rainwater, the musk of bears. When I wade from the lake, my clothes are dry. The sun hangs in the treetops, turning the forest gold.

A blizzard of feathers darkens the sky. Twelve swans swarm the bank of the lake, their eyes sharp with suspicion. They circle me, swiping at my ankles with their beaks.

I should recognize her by the way she holds her head or by the slant of her eyes. They fix me with an unblinking gaze, their necks weaving like snakes. But I do not know her. I don’t know what she wanted before she met my father, or why she stayed with us so long. I don’t know who she would have been, or what she would have painted.

They crowd me, striking my sides, my arms, my thighs, leaving angry stripes on my skin. One rears back, revealing a bare patch just inside her left wing.

The feather is still in my pouch. Its barbs are clean and white. I place it before her, pointed at her breast.

The swans fall still. My skin throbs where the marks are turning blue. The swans enfold me and press their bodies close. The one with the bare patch lays her head in my lap. I curl my fingers around her neck and close my eyes.

“I came to bring you home,” I say.

She turns cold, contracting into coils sliding around my waist. Then she expands, her scales shifting to thick, hot fur. She grows until my arms cannot reach around her. She thrashes and bites, slicing my skin, but I cling to her and do not cry out. She breaks into a swarm of hornets, and I gather them in my arms, even as they drive their needles into my chest and neck and cheeks.

The hornets collapse in on themselves. The sting dissolves. My arms are empty.

Fingers trace my forehead, my eyelids, my tears. I was the best thing in her life, she said. I keep my eyes closed tight, memorizing her touch even as it fades.

The beat of wings forces me to kneel among the leaves churning across the forest floor. The trees thrash in anger. The wind rebels on my behalf, but the swans are stronger. They rise, sweeping toward the pines. Her long neck arches as if in pain. Her mournful call shivers, as it is whipped away by the wind.

The sun casts her shadow on the pond. Her feathers stand out in relief, like the prints I used to make in school by resting an object—a coin, a key—on paper. The sun burns the world away around each feather, leaving it imprinted in negative space.

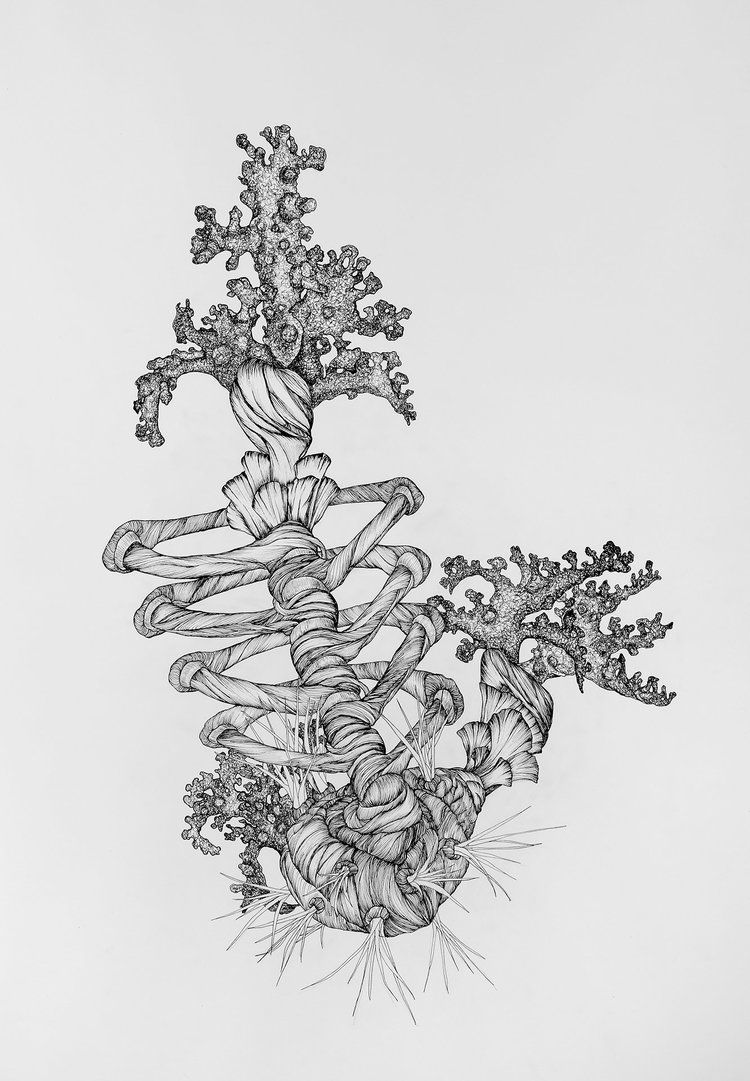

Art by Maggie Nowinski.

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#33999′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

[av_one_half first]

[/av_one_half]

Lara Ehrlich’s writing appears or is forthcoming in The Massachusetts Review, The Columbia Review, The Normal School, The Minnesota Review, SmokeLong Quarterly, and River Styx, among others, and she is working on a short story collection. To learn more, visit www.LaraEhrlichWrites.com.

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#33999′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]Nike sneakers | Air Jordan