[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#1f4378′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

–an excerpt from her memoir, Little Boats

Six years after my name was gifted to me, my parents moved us to the Swinomish Reservation. There was tribal land in the family and my parents saw an opportunity for an easier life. I saw a dark forest and a lack of ocean. I thought I’d be close to mermaids if I could be close to the water. As a young girl, I wanted the world of mermaids to be real. I learned to hold my breath underwater at the community pool, unafraid. This was especially difficult because I am an asthmatic; breath has always been a powerful and terrifying thing to me. The idea of drowning without water, of choking on nothing, of suffocating simply because your body forgets a basic function, has haunted my nightmares since childhood. I have always wanted gills.

Mermaids, according to Hans Christian Andersen and Walt Disney, have always wanted something. They want it so desperately they will sacrifice anything to get it. Most often the thing is escape. They want legs. They want the ability to leave. They want a prince. They want anything other than what they’ve got.

My first day of school after moving to the reservation, I stepped out into the dim, blue light of morning. It felt like something was wrong with my legs. I was nine years old and this was my first time boarding the bus that would take me to La Conner Elementary School. The move from city to woodland was frightening for various reasons. Mermaids—those half-women, half-fish—represent the ultimate half-breed, an obvious kind of duality. A neighbor would never swim up, poke Ariel in the chest while eyeing the scales of her fin, and say, “Hmm, you don’t look part fish.”

There was no tribal school to attend on the Swinomish reservation; instead all the kids were shuttled across the channel to La Conner to attend the mostly white school. Here was a pool of strictly fish and strictly non-fish, corralled together, and here I was, a pale person in a hand-me-down pink windbreaker. In my shabby floral print leggings, oversized denim button-down, and K-Mart brand sneakers, I inched out. I looked back at our trailer, at my new home as it stood against the trees. My parents’ bedroom light glowed orange in the dark. I wanted to turn back. I studied my outfit as I crunched the gravel of our driveway beneath my sneakers. The only new things were the cheap magenta knockoff Keds and the plastic barrette in the tangled mess of my brown curls. I inhaled shakily, my chest sputtering, and then exhaled. The doctors at the tribal clinic would later inform my parents of my asthma, but this morning the stifled breathing was still a mystery.

The yellow school bus streaked through the cedar trees. I swallowed air and quickened my pace. Climbing up the big steps, I moved past the bus driver with her sunken face and stared out at the columns of strangers. Fingers of panic closed around my throat and I reminded myself to breathe.

I saw Starters jackets with shiny zippers cutting through the brightly colored sports logos. I saw jerseys on the kids from the rez, Polo shirts and name brands on the kids from La Conner. I looked down again at my collage of hand-me-downs. I shuffled to a seat and stared out at the wall of trees zooming by. Groups of kids huddled together, laughing at jokes I didn’t understand. Whispering and sniggering came from faces, brown and white and all unfamiliar. The only other native kids I had ever been around were relatives. The only white kids I had been around were my peers at the inner city elementary school I attended before my parents decided to move us here.

“They’re just curious about you,” my mom would say each afternoon when I’d return home, complaining that no one had talked to me again. “They’ll come around.” I told myself she was right. I was new and from the city, and I let this strange confidence root itself in me.

One afternoon, a girl in the third grade finally approached me. Her name was Anna and she lived three stops ahead of mine on Indian Road. She usually sat in front of me on the afternoon bus rides home. I watched her golden head rest against the vinyl seat. It bobbed and bounced when she laughed with the gaggle of girls that surrounded her, and when she’d flip her blonde locks over her shoulder I smelled strawberries and sugar, a cloying aroma that seemed to belong in shampoo commercials on television. She beamed around to face me unexpectedly one afternoon.

“Hi!” she said brightly. “You’re in Mrs. Middleton’s class with me, right?”

I nodded, a feral instinct tugging me further back into my seat. Unabashed, Anna launched into a barrage of questions. She wanted to know what Seattle was like. She was confused when I shrugged at her question, “But you’re a white girl, right?”

“No. I mean, yes. But I’m also Indian,” I began, but she laughed and cut me off.

“So,” she smiled, “you’re only part Indian?”

Part Indian. Like only half of me was bad. I shivered a little. Anna glowed with a kind of cleanliness I would never know, not even on the mornings after my family’s weekly trips to Thousand Trails Campground. In those days, we didn’t have running water on the property. The nights my brothers and sister and I enjoyed the luxury of hot water, shampoo, and soap always felt decadent. I’d go to bed those nights huffing my perfumed hair, feeling clean and proud, but there wasn’t enough berry scented Herbal Essences shampoo in the universe to make me as squeaky clean as Anna.

Before her stop came up, Anna smiled, showing teeth. “You know, that first day you got on the bus, I kind of just thought you were some ugly girl. But you’re nice.” She flipped her hair, perfume strawberries splashed me in the face, and I watched her glide off the bus.

I decided to invest some time and energy into my appearance. Climbing up on the toilet to reach into my mom’s makeup bag on the shelf was the first step. I wanted to transform, but I thought I’d better practice first. One Saturday morning, I spent the better part of an hour tugging my hair back into a scrunchy and applying my mom’s makeup to my face. I wanted to look more like her. People always talked about how beautiful she was. I surfaced from the bathroom to the roaring laughter of my siblings. Even my parents chuckled. My mom’s foundation was about three shades darker than my own skin, and I looked like I had rubbed my face in dirt. I scrubbed my face back to its natural state and swore off makeup forever. I went back to my normal routine of life on Indian Road, afternoons spent in the woods with my brothers and sister, hunting salamanders and poking around in the depths of decomposing logs.

Tara was my first real friend at school. I met her walking across the blacktop at recess one morning. I saw her first. Her brown hair fell to her shoulders; her eyes disappeared when she smiled a big smile. But what really caught me was her light blue denim jacket. It was a perfect fit, definitely not a hand-me-down. Its sleeves weren’t rolled up into ridiculous little cuffs around her wrists. There were no stains, no burn marks or holes, and the jacket fell right to the waist of her blue jeans. I had never seen a jacket so new. Most importantly, the back was adorned with a giant, sparkling decal of The Little Mermaid. Painted in glittering colors, Ariel posed, her ruby hair floating in the sea of that jacket. I was bewitched and stood back observing Tara. She jumped off the monkey bars and chatted with the girls around her. Then she walked right up to me.

“Hi!” Even her freckles sparkled. “What’s your name? Do you wanna come to lunch with us?”

I must have looked like a wounded animal answering her questions. I was worried at each new inquiry that Tara’s face would drop, but it never did, not even when I told her where I lived. Tara wasn’t fazed by me living across the channel, on the rez. She kept chattering on, smiling and telling me about her mom’s house out in the farm flats and her dad’s house in town by the channel.

The jacket became an obsession. I coveted it so intensely that I dreamed of strutting around school with it, only to wake and find the same pink, thrift-shop windbreaker in its place. I begged my mother to take me to the mall, to the Disney Store where I knew the jacket lived.

My mom came home late every night after the long commute back from the native group home where she worked. Exhausted, she’d ask us kids if we’d eaten, throw together a box of macaroni and cheese, and check on chores and homework. One night, she leaned against the sink, still in her work clothes—a burgundy pencil skirt and white blouse—doing dishes. I paced around her excitedly. I described the jacket in all its detailed glory. I explained to her that Tara and I would have matching jackets. My mom put the last plastic bowl on the wooden dish rack.

“Who is Tara?”

“Tara is my new friend,” I beamed. “She lives in town!” My emphasis on in town caused my mother to look up from the dish towel she was patting her hands with. Her lips pursed the way they always did when she was irritated.

“In town, huh?”

“Yeah.” I circled back to the jacket.

My mom frowned. “We’ve already done the back-to-school shopping,” she snapped. “And regardless, we certainly can’t afford to just buy all you kids fifty dollar jackets. It’s absurd! The one you have is fine. Enough about the stupid jacket!” She asked about my homework, looked at the clock, kissed me, and said goodnight.

The jacket was more than just status though. Ariel and I had a history. When I was six, my mom had taken me to the Cineplex, bought me a cherry Coke and a bucket of popcorn. This was a magical luxury—the neon lights, the smell of butter, the rainbow assortment of treats displayed behind glass. There was something extravagant about that first march down the dark theater aisle, holding an armload of candy boxes and sucking on the plastic straw of my soda cup. I felt rich. This is how kids on television went to the movies. The animated fairy tale exploded from the big screen in a world of color: singing fish, talking crabs, an evil sea witch, a handsome prince, and of course, that iconic redheaded merprincess, longing for a better lot in life. The Little Mermaid had a bunk deal and I identified with that.

The ocean became my biggest fantasy. Ariel was hellbent on trading in her fins for a pair of legs to walk on land, and I was her opposite. I longed to wake up one morning to find webbing between my toes, to slowly morph into half-fish and disappear beneath the surface. I knew I was just like that fiery and mischievous mermaid, only instead of a sea cavern full of treasures, I escaped into the forest behind our trailer. I built forts and talked to trees and daydreamed about leaving. That was always the Little Mermaid’s deepest desire—leaving.

My mom catered to my mermaid fantasy when she could. We couldn’t afford the jacket, so she tried to make up for that by throwing me a mermaid-themed birthday party. There on the table was a giant cake in the shape of Ariel. Her green tail, peachy torso, purple seashell bra, and crimson hair were all accurately portrayed in frosting and sprinkles. In the kitchen was a mess of pots and pans, different shapes she had used to sculpt and cut out my mermaid-shaped cake. I was horrified as we began section-ing her off into chunks, carefully serving up squares of green fins, the belly button, a serving of purple seashell, her pink mouth. But as I watched my girlfriends around the table in their triangle party hats smile, as streamers fell in purple and green ribbons beyond their heads and they enjoyed their personal portion of mermaid, I swelled with pride.

On ferry rides out to my grandparents’ property on the peninsula, I squinted hard through the waves. I was determined to catch a glimpse of the shining scales of mermaid fins. During family camping trips out at the beach property, my great grandmother and grandfather would get up at sunrise to take the ladder down the cliff to the ocean where they would spend the morning digging for clams. I’d explore the beach’s early morning tide pools while they watched for the squirt of geoducks in sand. I played out entire mermaid scenarios in my head as they filled their buckets with the clams we would eat for dinner. I’d carefully climb out over the rocks, squint to the horizon and wish hard that the merpeople who lived beyond the breakers would come back for me.

My great grandmother was a storyteller. I would sit perched on the edge of my stump during the nighttime campfires as the fire cracked and lit her face in the dark. The lines in her brown skin were faint and, though she was past sixty, her cropped hair was a dense black to match her eyes that glittered dark against the firelight, the cracks around them moving as she spoke. My great grandmother told the stories in our tradi-tional Coast Salish language, Lushootseed. I hung on each Lushootseed syllable, eager to hear it repeated in English to make sense of the story. When she told stories, the whole family quieted to hear her words amid the crackle of cedar burning. Desperate to impress her one afternoon after a long morning of clamming and fishing, I sat down next to her as she cleaned and gutted a fish. I decided to test out my own skills as a storyteller. I sucked in a deep breath and launched into a play by play of Disney’s The Little Mermaid. I left nothing out. I even sang the songs. My mother had taken me to the Seattle Public Library, and I had educated myself on all things mermaid. I knew it was based on Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid,” and I had seen the picture books and watched the animated film, discovering to my horror that the mermaid princess doesn’t marry the prince in the original but tragically turns to sea foam at the end. I proudly gave this epilogue after I’d finished my performance. My grandmother graciously listened. She smiled and nodded. She praised me when I was finally finished.

“You know,” she said that afternoon at the beach. “Your ancestors have their own sea princess.” I nearly fell off my stump. I listened intently as my great grandmother told me for the first time, the story of “The Maiden of Deception Pass.”

The story tells of a maiden who lived with her people down by the water’s edge. How one morning while gathering clams with her sisters the maiden stepped into the ocean and felt it grip her. She heard a voice as the ocean spoke to her, reassuring her he only wanted to look on her beauty. Each day she’d return to the beach to collect oysters and clams, and each day the ocean spoke to her. He beckoned her to come live with him; he pled for her to be his bride. One morning, the voice did not come, but a man emerged from the water, tall and handsome. He walked the girl through the village and asked her father for her hand in marriage. Her father refused, unwilling to part with his daughter and certain she would die in the ocean. The ocean left but warned the village that if the girl could not be his bride he’d bring on a drought. True to his word, the rivers dried up and there were no clams or fish for the maiden’s people to eat. The maiden’s father finally refused to see his people go hungry and agreed to the marriage on the condition that his daughter be allowed to return to her village once a year, able to walk on land and be with her people. The ocean complied, and the two were married. Below the sea the maiden was happy. She was in love and enjoyed her new home, but she knew her people missed her and soon enough it was time to return home. Each year that the girl returned home it became more difficult for her to walk on land. She returned each year covered in more bits of the sea. On the last year she returned, her father saw the barnacles on her face, the sea kelp that was her hair, and heard the difficulty in her breath. He told his daughter he couldn’t bear to see her in such discomfort and released the ocean from his promise to return the maiden to her people each year. The people of the village lived happily with their abundance from the ocean and knew that each time they saw the long streaming pieces of sea kelp floating in the narrow waterway of Deception Pass, that they were seeing their maiden’s hair and that she was still with them.

The Maiden of Deception Pass didn’t just disappear into the ocean; she became the ocean. She sank into the sea to save her tribe from starvation. She returned each year like Persephone. But unlike Persephone, she went willingly into the depths, that underworld. This empowered her beyond the other sea maidens with whom I had become so obsessed. Mermaids were always bargaining with the sea witch in order to trade their fins for legs. Their motives were usually selfish and usually resulted in their demise.

Selkies were a different kind of tragedy. Like mermaids, the half seal women of these Scottish folktales always sacrificed their life beneath the sea to be with human men, to be on land. The men often tricked the selkies, hiding their seal coats from them so they couldn’t return to the sea. The selkies became depressed. They missed the ocean and their seal lives. They were captives. Unlike mermaids and selkies, this sea-maiden of Deception Pass wasn’t a victim but a warrior, willingly braving the deep sea to save her people and find happiness.

I begged my great grandmother to tell and retell the story as often as she would. I ran along the beaches with new enthusiasm and pride. The ocean and I were practically related. I hopped along the stony shores, ecstatic each time I’d see the rubbery shine of sea kelp on the surface. I’d scoop large bits of the maiden’s hair up in my arms, cradling its slick weight.

Hearing the story of the Maiden of Deception Pass only intensified my mermaid obsession. Like Ariel, I felt her in me. The only problem was there were no Maiden of Deception Pass Barbie Dolls or backpacks. I was stuck with hoarding all the Little Mermaid objects I could get my hands on.

I had a Little Mermaid lunch pail, thermos, sleeping bag, night-shirt, and all the dolls available. Each birthday or Christmas brought a new Ariel artifact into my life, some new talisman that I could tote around. But the jacket was the next level. It wasn’t some silly doll or nightie. This was fashion. This was grown up and somehow was sure to elevate my status from new girl who lived in a trailer, who wasn’t white but also wasn’t Indian, to Tara’s new and popular best friend. Still, my mother refused. “We can’t afford it.” She said it so often that it began to sound as regular as breathing. Inhale: We can’t. Exhale: Afford it.

One Sunday morning, my mom brought home a surprise. She had gone out for errands and returned with a giant bag from the craft store. She worked well into the evening, tracing and painting. By the time the sun set, she called me into the kitchen to show me what she had made. She held up a Levi’s jacket. It fit perfectly. If it was second-hand, you couldn’t tell. And on the back was a near flawless replication of Tara’s Ariel decal. I burst into simultaneous tears and laughter. I jumped up and down. I quickly put the jacket on and tore it off again to admire the shimmering painting of Ariel. It looked like the real deal.

My mom pointed to the display of fabric paints strewn across the kitchen table.

“Do you want to add something?”

I nodded. She left the room as I scooted up to the table and picked out a pearly, sea foam green paint. I concentrated hard. I bit down and chewed on my lip. I wanted my lines to be precise. When my mom came back into the kitchen I was sitting cross-legged in my chair, waiting for it to dry. “Oh,” she smiled sympathetically, “It’s l-i-t-t-l-e, dear.”

I looked down at my drying paint: The Littel Mermaid stared back at me, already drying in its pearly finish.

We scrubbed with wet towels and dish soap, but the damage was done. Littel was still visibly clear through a cloud of pale green paint, hovering above my mother’s pristine replica. My mom reassured me it was fine.

“No one will notice honey. Your hair will cover it.”

The jacket did look pretty good. I put it on the next morning and shook my hair over the collar. Maybe it did cover the horrible, puff-paint typo. I held my head high as I boarded the bus. I sat in my usual seat, kicked my legs back and forth, and hummed. I wore my jacket through first and second period. I wore it into the cafeteria at lunch time. Sitting next to Tara I ate my lunch and she smiled. “It looks so good,” she said. “Your mom did such a good job.”

Anna and a group of girls sat one table over and as I bit into my PB&J on wheat, I began to feel their eyes burning into my denim back.

“Oh my god,” Anna squealed across the cafeteria. “Is that a hand painted Little Mermaid jacket?” She had gotten up and was standing behind me now. I nodded, still holding onto the pride of my mother’s fabric paint masterpiece. I sat in the silent wake of what came next. I thought of The Little Mermaid, The Maiden of Deception Pass. I thought of sea kelp moving on water. The wave crashed. Anna’s laughter was a shrill and stinging thing. “Well, whoever did it is STUPID,” she announced. “They spelled little wrong! You should take it back.” She walked away, just like that day on the bus. Only this time there was no question. I was just some ugly girl. Worse. I was now just some stupid girl, too. I trembled a little and stared at my plastic tray.

Tara smiled her sympathetic smile. “It’s really not that noticeable, I think it looks nice.” I recognized her kindness, but it was too late. I was already broken apart, like sea foam.

I walked slowly down the gravel driveway towards our home that afternoon. The coat, a bundle of shame tucked under my arm. I pulled the metal door to our trailer open and bolted down the narrow hallway. I glanced at my mom, who sat chatting on the telephone before I slammed the door to my small room shut. I hurled the jacket into the closet and sobbed. I wouldn’t ever wear it again. I heard my mother outside the thin walls of my room and sucked in a ragged breath.

The trailer started to shrink around me. Things felt smaller and I spent more time in the woods. I started pocketing my lunch money, skipping meals or shamefully sneaking the bland peanut butter and jelly sandwiches that were free in a large plastic crate next to the food line. I didn’t dare remove the jacket from its crumpled pile. I shoved my saved-up lunch money between my box spring and my mattress, waiting until I had enough to go to the mall, to buy something new to wear. I just wanted to look like everyone else. I’d come home and take off my pink windbreaker, open my closet, and try not to look at the denim coat in a pile in the corner of the small cupboard. If I looked too long, I’d see the glittered lines, so careful and precise. Ariel’s face would appear, distorted in some fold of fabric, and I would see my mother, carefully bent over our folding table, patient and steady handed.

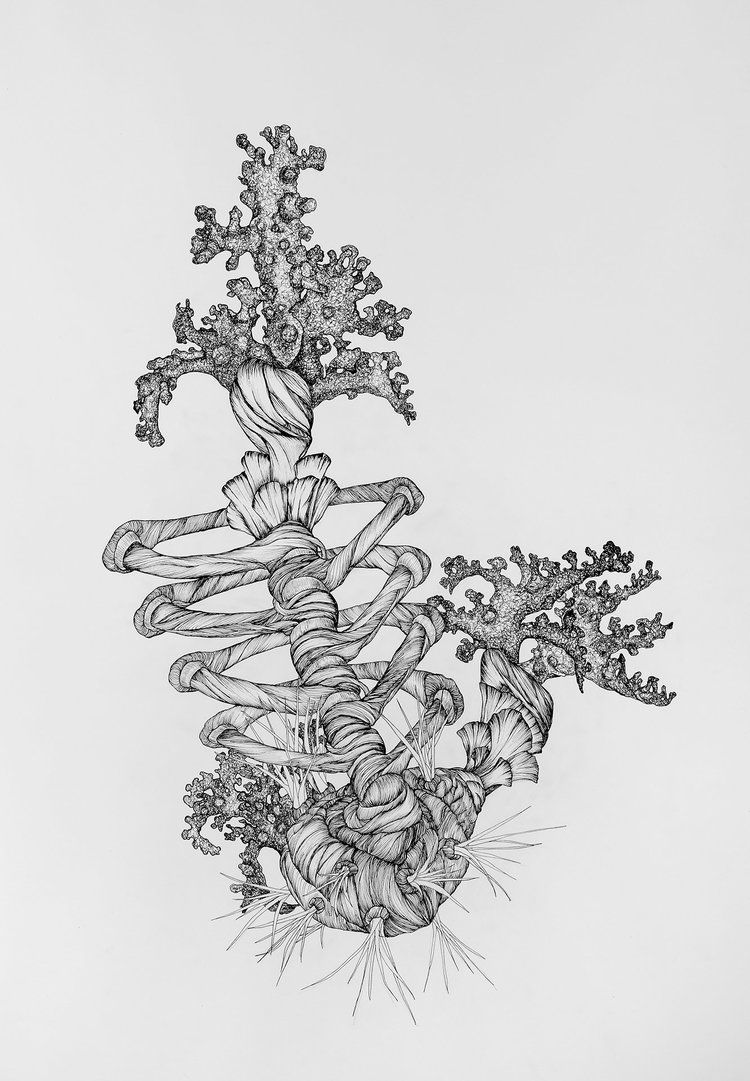

Art by Maggie Nowinski.

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#1f4378′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

[av_one_half first]

[/av_one_half]

Sasha LaPointe is a member of the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe. Her work focuses on trauma and resilience, sexual violence, and indigenous feminism. She’s inspired by the work her grandmother did for the Coast Salish language revitalization, loud basement punk shows, and what it means to grow up mixed heritage. Her work has appeared in The Rumpus, Indian Country Today, Luna Luna Magazine, The Yellow Medicine Review, The Portland Review, AS/Us Journal, and THE Magazine. She received her MFA from The Institute of American Indian Arts with a focus on creative nonfiction and poetry.

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#1f4378′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]Sportswear free shipping | Women’s Nike Air Max 270 React trainers – Latest Releases , youth boys nike sunray sandals clearance outlet