The literary world has been applying the “-punk” suffix to science fiction sub-genres so frequently and for so long that it sometimes verges on self-parody. It all began with cyberpunk, a description of the 80s noir-esque SF of Bruce Sterling, Rudy Rucker, and of course William Gibson. This was soon followed by steampunk, a term which came to refer to both retrofuturistic SF and a fashion style that mashes up Victorian and post-industrial elements. In the wake of that has come biopunk, dieselpunk, nanopunk and a host of other -punks: tags for sub-genres and sub-sub-genres proliferating, spread by fans and book marketers but not always universally recognized throughout the industry.

The idea of solarpunk as a distinct genre has only emerged in the last few years. Mostly self-applied by writers of speculative eco-fiction, solarpunk has become as much a philosophical and esthetic stance as it is a term of critique. The proponents of solarpunk present to us a future that works, as much as it may still struggle with the consequences of climate change and rapacious capitalism. What, then, is there to distinguish it from techno-utopianism or post-hippie fantasies like Ernest Callenbach’s Ecotopia? “There’s an oppositional quality to solarpunk,” wrote Adam Flynn in 2014’s Solarpunk: Notes Toward a Manifesto. “But it’s an opposition that begins with infrastructure as a form of resistance.”

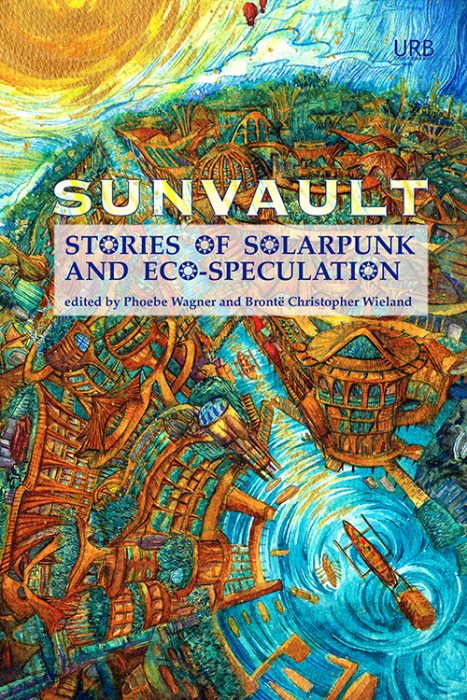

A new anthology, consisting of 19 short stories, ten poems and seven pieces of artwork, is the most recent vehicle to give voice to this nascent movement. Sunvault: Stories of Solarpunk and Eco-Speculation came together as the collaboration of Phoebe Wagner and Brontë Christopher Wieland, two MFA candidates in Creative Writing and Environment at Iowa State University. When they came to Iowa in 2015, as avid readers as well as writers of SF they both lamented the fact that “the environment was an antagonist” in that genre, “already destroyed to the point of no return, or simply not a consideration” (from the “Editors’ Note”). They saw in what was then a small Tumblr coterie the roots of a different kind of near-future SF. And given that near-future SF virtually always means dystopian SF these days, these writers were (to paraphrase William F. Buckley’s description of conservatives) standing athwart science fiction, yelling Stop, at a time when no one is inclined to do so, or to have much patience with those who so urge it. In 2015, there was as yet no anthology of solarpunk works in English. So, working in what little spare time was available to them as graduate students, Wagner and Wieland commissioned pieces that exemplified the qualities they were seeking, and reviewed over two hundred submissions from around the planet. They launched a successful Kickstarter to complete the project, which was published in August 2017.

The selection of short stories is as eclectic and diverse as the authors, drawing from multiple styles and languages. The masterful Daniel José Older, author of the Shadowshaper and Bone Street Rumba fantasy series, contributes “Dust,” a tale of uprising that plays with fluidity of gender and space-opera tropes to tell an ultimately hopeful story. “The Road to the Sea,” by the Israeli author and Campbell Award laureate Lavie Tidhar, is both elegiac and uplifting. “Boston Hearth Project” by T. X. Watson is an action-packed, propulsive story that imagines a near-future Occupy with augmented reality tech. Iona Sharma’s “Eight Cities” explores faith and consciousness against the backdrop of a Delhi inundated by rivers swollen as a result of a changing climate. And “Speechless Love” by Yilun Fan (translated from Mandarin by S. Qiouyi Lu) tells the story of a relationship between two “stratospherians” in a future where “atmosphere colonization replaced space colonization.”

The inclusion of poetry and visual art in the anthology emphasizes the vision of solarpunk as a movement rather than merely a literary genre. The language in the poems runs the gamut from the technospeak of “Strandbeest Dreams” by Lisa Bradley and José M. Jimenez, to the more traditional SF imagery in “light star sail bound“ by Joel Nathanael, to the flowing lyricism of “The Seven Species” by Aleksei Valentin. The artworks, like the poetry interspersed throughout the anthology, are intricately detailed and somewhat reminiscent of art nouveau: a movement not entirely dissimilar in its evocation of the natural world, its ease with the romantic, and its insistence on being of its historical moment.

In their Note, the anthology’s editors emphasize the importance they placed on including a diversity of voices. Solarpunk is very much a global movement: indeed, the first anthology of solarpunk fiction was published in Brazil in 2012 (with a Kickstarter currently underway to publish an English translation). The true genius of this work lies in its essence as a community project, as a labor of love by writers, artists and editors. It takes more than a buzzy label to make a movement, and the energy of these student-editors – coupled with the outpouring of interest and involvement across national boundaries – suggest that solarpunk may be finding resonance in this often-fearful age.

Publisher: Upper Rubber Boot Books (August 29, 2017)

ISBN 978-1937794750, 254 pages

$13.99