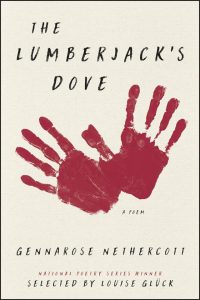

This fall will be many readers’ first introductions to GennaRose Nethercott’s potent, monstrously creative poetry. Her debut book, The Lumberjack’s Dove, has earned the loyalty of Louise Glück, queen of night poems here in America, and will be published in October as a National Poetry Series winner. If you don’t know GennaRose yet, you can find her poems all over the internet—but your paths may have crossed already.

This fall will be many readers’ first introductions to GennaRose Nethercott’s potent, monstrously creative poetry. Her debut book, The Lumberjack’s Dove, has earned the loyalty of Louise Glück, queen of night poems here in America, and will be published in October as a National Poetry Series winner. If you don’t know GennaRose yet, you can find her poems all over the internet—but your paths may have crossed already.

More than any other young poet I know, GennaRose has worked to spread her writing’s reach far and wide, body to body. She’s busked custom poems-to-order in cities across America and Europe (you can order online, too); architects and small business owners have commissioned her words, paired them with million-dollar homes and displayed them as product copy; she is in constant collaboration, always crossing her work with other creative disciplines; she winters in New Orleans, has slept on a bookshelf in Paris.

GennaRose is an old friend, a co-conspirator—we ran a ruthless kindergarten gang together, and more recently an indie lit mag—and a fellow Vermonter. Over the long, storm-addled winter, we paper airplaned this brief interview between New Orleans and Montpelier:

From the passersby who prompt your poems-to-order to the musicians featured in your recent album of ballads, a diverse array of perspectives, both artistic and otherwise, have been welcomed into your creative process. As a poet, what is the significance of collaboration and community to your work?

On the purest level, my collaborative work stems from loneliness. Being a writer is often immensely isolating, and I’ve long struggled with how to maintain my creative practice while still being a member of society, still connecting with other people. Often, I fail at balancing the two. However, with collaborations such as the ballads or the poems to order, I’m able to escape that isolation—and allow forging relationships with other people to be not a distraction, but rather an essential part of the creative process.

Beyond that, working with other people and other artists allows my work to transcend my own limitations. Take the Modern Ballads album, for example: I wrote a series of narrative ballads that I wanted to take the form of songs. I’m not a skilled enough musician or singer to lend them the sounds I desired for them, so I partnered with a team of professional musicians who set the ballads to music and performed them. Thus, the lyrics were able to far exceed the limits of my own skills, and become better works of art. Other creators are amazing! Don’t get so bogged down by a sense of do-it-yourself egoism that you prevent your work from being as good as others might help it grow to be.

Could you talk a bit more about what inspired the Modern Ballads project, and what drew you to the ballad form in general?

The idea for Modern Ballads first materialized when I was living in Scotland, studying oral folk traditions as part of my undergrad. I became infatuated with the work of ballad collector Francis James Child, who traveled England and Scotland in the 1800s, gathering and transcribing traditional songs and poems. At the core, I was mainly drawn to the storytelling aspect—ballads, by definition, are poems/songs that tell a story. They’re narrative, telling of illicit love affairs and murders and rogue fairies. They have a mystical quality to them that enchanted me. I thought, How cool would it be to write a series of new ballads, based on, and slightly subverting, those traditional forms? To study the Child Ballads, and create something contemporary? And then have a bunch of bands set them to music? At the time I tabled the idea, because I didn’t know any musicians. Then four years later, I moved to Boston and fell in with the folk music scene—and now I know too many musicians. So figured I may as well make use of ’em.

Your work as a folklorist clearly influences the majority of your poems and stories. In your writing—and in the writing world at large, if it’s not too much—what are some essential ways that folklore and literature intersect? And for that matter, have you encountered any fundamental conflicts between the two fields?

At the core, folklore and literature are both about reflecting the society which creates them—designed function as a mirror of the time and environment in which they were born. But where they differ is largely in process: Literature is single-authored, written down, and static, while a folktale is authored by many voices, passed through oral storytelling, and changes with each telling to adapt to whatever time and circumstance it’s in. Those differences aren’t in conflict, however—they just both fulfill different roles in the world of storytelling. And for me, it’s the storytelling ability of each that’s fascinating. The potential to snatch away a reader/listener and deposit them in some other life.

Your forthcoming book, The Lumberjack’s Dove, tells the story in poems of a lumberjack whose hand, when chopped off, becomes a dove. The idea reminds me of a quote from the folklorist and fairy tale scholar, Jack Zipes: “If there is one ‘constant’ in the structure and theme of the wonder tale, it is transformation.” To you, what is the greater significance of transformation within folklore, and within your own writing?

Shapeshifting is my ultimate obsession in storytelling. Because as we all know, change is unyielding and constant. It never sleeps. Shapeshifting stories allow this truth to manifest literally—so ultimately, transformation is ever-present in lore because it is ever-present in life. In shapeshifting lover tales, for example, where a sweetheart morphs between an animal and human form, it forces us to ask ourselves: Do we truly know those we love? Can we be sure they will maintain the Selves we know them as? At what point do we stop recognizing our dear ones? Ourselves? And in the case of Lumberjack, in which a part of his body, a part of himself, is severed and transformed, it speaks to how once something, even something we consider fully ours, is taken away, it belongs to itself. It becomes something new. And once something changes, truly changes, to the point of sprouting wings or fangs or scales, nothing can ever return to what it was.

As a winner of this year’s National Poetry Series, The Lumberjack’s Dove marks your arrival on the national literary scene. What’s your ideal public role as a writer with national readership?

I’m still figuring this out, since that position is so new and strange and surprising for me. But ultimately, I just want to be able to continue writing and have my work connect with readers in a way that offers some sort of solidarity and giddiness. I want readers to feel seen when they encounter my work. And personally, I want to be on the road as much as possible, touring my writing, doing readings, meeting people in-person. I’ve always been drawn to the traveling bard archetype, so part of me wants to embody a modern version of that—to serve as a sort of footsoldier for language and story, an ambassador.

Here’s a quickie—what have you been reading lately? What literary happenings have you excited?

I just read The Bear and the Nightingale, which is a beautiful Russian fairy tale by Katherine Arden (the sequel was just released, as well). Before that, I gleefully shimmied my way through Before the Devil Breaks You, the third book in Libba Bray’s The Diviners series, which are YA books about teen psychic flappers in 1920s New York City who fight ghosts and investigate occult murders. All the best things! And I’m always re-reading everything Kelly Link ever wrote. I’m super into contemporary fabulist fiction writers. If you’ve ever been near me when I’m tipsy at a party, you know this, because I basically just ramble the words, “Kelly Link! Aimee Bender! Karen Russell! Angela Carter! Helen Oyeyemi!” on repeat like some kind of sports chant. Oh, and I just got Her Body and Other Parties by Carmen Maria Machado, which I haven’t started yet but am very excited to dive into.

Care to share any new projects you’re working on?

I’ve been chipping away at a book of spooky short stories (possessed roosters, paper children, women turning into houses, etc…), and agent-hunting for another manuscript of mine which is a bestiary of imagined creatures. Otherwise, prepping The Lumberjack’s Dove to come out in the fall, and Modern Ballads to drop in the early spring.

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#1f4e78′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

[/av_one_half]

[av_one_half]

GennaRose Nethercott is the author of The Lumberjack’s Dove (Ecco/HarperCollins, 2018), selected by Louise Glück as a winner of the National Poetry Series. Her other projects include A Ghost of Water (an ekphrastic collaboration with printmaker Susan Osgood) and the narrative song collection Modern Ballads. Her work has appeared in The Offing, Rust & Moth, PANK, and elsewhere, and she has been a writer-in-residence at the Vermont Studio Center, Art Farm Nebraska, and the Shakespeare & Company bookstore in Paris.

She tours nationally and internationally composing poems-to-order for strangers on a 1952 Hermes Rocket typewriter—and is the founder of the Traveling Poetry Emporium, a team of poets-for-hire. Nethercott holds a degree in poetry, theatre, and folklore from Hampshire College. A Vermont native, she has lived in many cities across the US and Europe, but is always drawn back to the forest.[/av_one_half]

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#1f4e78′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

jordan Sneakers | Best Nike Air Max Shoes 2021 , Air Max Releases and Deals