[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#372a55′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

One thing about fear is that it’s stronger than the average human body. Another thing about fear is that it spreads quickly in large crowds. The Director wants his viewers to keep these facts in mind when watching his film. He realizes, of course, that this isn’t about what he wants; he was commissioned to make a documentary about a humanitarian crisis. Still, it’s his work. His art. That matters, too.

The Director is considering using subtitles to offer context: Since the rise of the regime in the neighboring state, X number of people have attempted to cross the border; of them, Y have succeeded, Z have failed, and approximately two dozen have been executed. XYZ is just how the Director is thinking about it for now—hopefully by the time the project is in post-production, things will no longer be weird with Andrea and he will once again feel comfortable saying, for instance, I need those numbers by tomorrow, whatever you have to do please, in that tone of his that means or else. For now, he is still tiptoeing, trying to gauge her mood before asking for a fucking glass of water, which is just such total bullshit considering he didn’t even ejaculate.

His aesthetic taste is kind of classy, clean, so he’s thinking: a simple white font on a black screen. But he’s also wondering if the subtitles are even necessary? Wouldn’t the average viewer likely know all about that regime? Maybe there’s no need to offer stats about those poor people trying to escape their country. It’s not that he minds more research; it’s that he minds needless work.

Bird’s eye view, camera way up top looking down down down, getting closer slowly, gently, only close enough for the pink red stain to pixelate into dots to become a sea of people, become many people, become specific people in a big crowd. Let’s pause here: freeze frame. We are about to get closer, and if the goal is to leave no dry eye in the audience, then there are many easy, obvious choices. But no. The Director wants his job to be hard. There’s a particular kind of male who’s the beneficiary of so many privileges that he develops a need to challenge himself, because he believes these self-created challenges legitimize him in a way he can’t quite articulate but knows is otherwise missing. The Director is that particular kind of male. So he chooses his artistic constraints: no elderly bodies, no people with pre-existing sickness. That would be too easy. No, to be the center of this zoom-in, one has to be of age and sound mind, and to have arrived at the checkpoint healthy. The goal is to still reveal, somehow, pain and despair—and not just any pain and despair but the kind that soundlessly screams: My country has disavowed me, I am a body trying to survive, etc. This screaming is done through physical language, facial expressions: clean camera work. Radical honesty is how the Director is conceptualizing it. For the sake of these poor souls, he has to reveal the angst in a manner that employs no trickery. People are dying, he tells himself, and he repeats the last word for effect: dying. Then he makes the face of a man who feels the gravity of death.

In the editing room months later, the Director is looking at so many different shots, an infinite number of shots, the kind of footage you end up with when your DP is undiscerning. The Director is annoyed, frustrated. Nothing feels right. The faces on the screen show no feeling at all, or appear to be faking, trying too hard. He is numb and he’s been doing this long enough to know what numbness in the editing room means. It means it’s all shit. Sometimes you have to power through this kind of despair until the sweet moment when—magically, mysteriously—you find yourself on the other side of the thing. You’ve crossed over. But this doesn’t feel like one of those times.

For a while now, the Director has been working with his therapist on being present. The therapist is practicing something called Nontherapy Approach. It’s kind of hard to explain Nontherapy, and to be honest it bothers the Director that the therapist has no diplomas hanging on his wall. It feels way too late—they’ve been working together for a year—to inquire about the man’s qualifications, although once or twice the Director made a joke about a Nondiploma Approach, hoping that the therapist would understand the joke to be a question (and offer an answer) but also understand the joke to be a joke (and therefore not resent the Director). The therapist seemed not to get the joke.

But most of the time he tries not to worry about the therapist’s training, because Nontherapy has been helping him accept himself. When he makes a mistake now—any kind of mistake, professional, personal, whatever—he knows it’s because of his past, so he tries to Locate the Authentic Area of Blame (usually his parents) and Redirect. Sure, his parents always meant well and did their best, but they also made a lot of mistakes, and never apologized. He walked in on them mid-orgy when he was six years old—this is really only one small example—and his mother shrieked and kicked him out, explained nothing. When he asked the next day—he had no idea what he saw—she pretended to be confused. She said he must have had a bad dream. In his darkest hours, the Director fears that this memory has rendered him incapable of love.

Redirecting helps. Free from feelings of false self-blame, the Director is able to inhabit his body, connect to the right now. Right now, in the editing room, he stretches. After long hours in a swivel chair, his muscles appreciate this momentary kindness, and he moans. It is a quiet, tame moan, a whisper of a moan; and yet it’s enough to invite memories of other moans. The Director’s mind is now moving away from the refugees who are seeking safety, away from the question of whether they’ll be granted asylum. Will they be shot dead? Or survive?It’s not that he doesn’t give a shit; it’s that he’s inhabiting his body. And his body is sending a clear message. There’s a buzzer in his work area, right next to the monitor, and he presses it. Andrea, he says, can you come in, please? I need you.

From Hunger Mountain Issue 22: Everyday Chimeras, which you can purchase here.

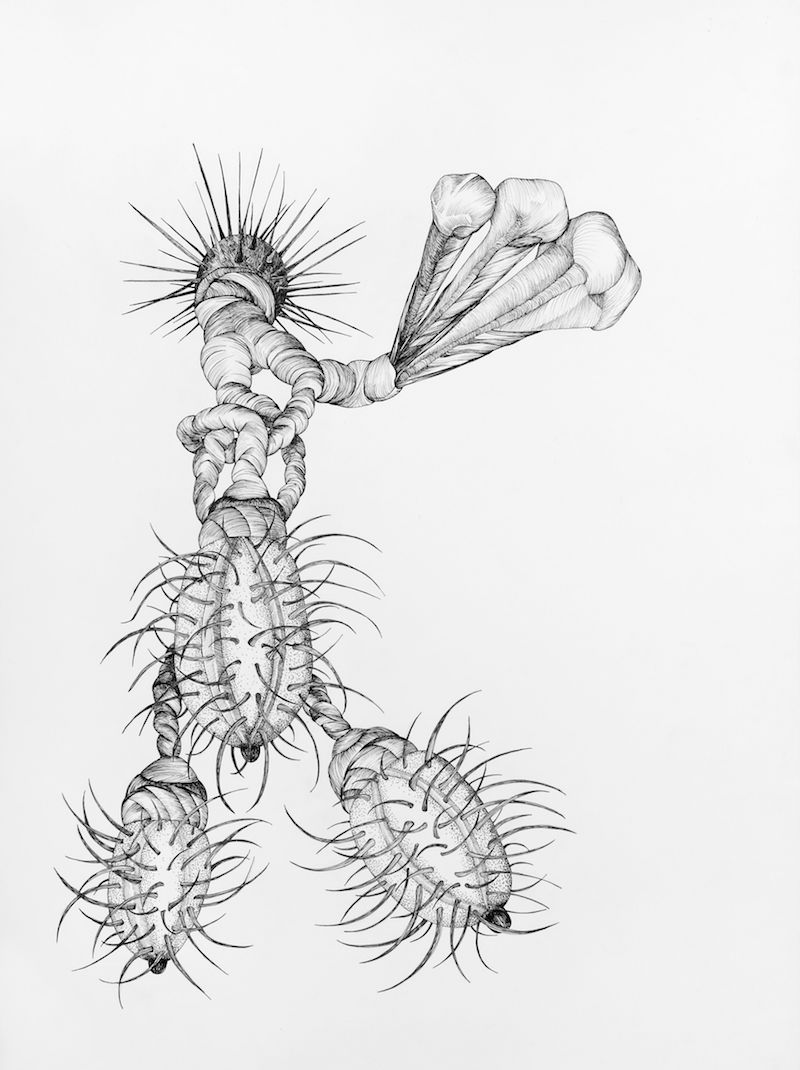

Art by Maggie Nowinski.

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#372a55′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]

[av_one_half first]

[/av_one_half]

Shelly Oria is the author of NEW YORK 1, TELAVIV 0 (FSG & RandomHouse Canada, 2014), which earned nominations for a Lambda Literary Award and the Edmund White Award for Debut Fiction, among other honors. Recently, she co-authored a digital novella, CLEAN, commissioned by WeTransfer and McSweeney’s; the novella received two LOVIE awards. Oria’s fiction has appeared in The Paris Review and elsewhere, has been translated to other languages, and has won a number of awards. She lives in Brooklyn, where she co-directs the Writer’s Forum at the Pratt Institute.

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#372a55′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”]Running sports | Air Jordan