[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#e45656′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”] Author’s Note The three short stories published in Hunger Mountain were written as part of an ongoing collaborative project with cellist/composer/instrument inventor Rafaele Andrade called Un-bow. The stories are named either for bow techniques or musical styles that Rafaele drew… Continue reading Music to Accompany Tim Horvath’s short stories in Issue #25—Art Saves

Category: Et Cetera

Why We Chose It: “Book of Leaves”

Philip Shackleton

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#e45656′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”] The short story, “Book of Leaves,” by Jim Kourlas met two of my broad criteria for the fiction I read during the fall reading period: it said something important, and it said it in an original way. The story sits… Continue reading Why We Chose It: “Book of Leaves”

Philip Shackleton

Backstage at the Rainbow Cattle Co.

Photographs by Evie Lovett

From 2002 to 2004, Evie Lovett photographed drag queens preparing backstage for the monthly drag show at the Rainbow Cattle Co. in Dummerston, Vermont…

BODIES SPACES

Photographs by Daniel Toby Gonzalez

Toby has found the greatest personal release exploring themes of masculinity—both his own masculinity and the way masculinity is perceived by society—and plans to dig further into the subject, attempting to “hit the bottom, if there is one.”

Paintings

by Don Fenestre-Marek

Over the past three decades, Don has worked in a variety of art media. He considers painting to have the broadest vocabulary for articulating the intersection of practical existence and spiritual inquiry.

Air

Photographs by Evie Lovett

Ten photographs from the series “Ari” by Evie Lovett. Originally featured in Hunger Mountain Issue 19: The Body Issue.

Collage & Mixed Media

by Matt Monk

[doptg id=”7″] Editor’s Note: Matt Monk’s design work was originally the featured art for the Prizewinner Issue—December 2014. In can now be seen in the Creative Nonfiction section. “In my collage and mixed-media work, I explore systems, typography, and narrative through experimental methods involving an expansive range of accretive and erosive processes including painting, gluing,… Continue reading Collage & Mixed Media

by Matt Monk

Illustrations

by Kerri Augenstein

…what a great opportunity to sit in the same space as all of the amazing authors occupying all of the brilliant content of Hunger Mountain.

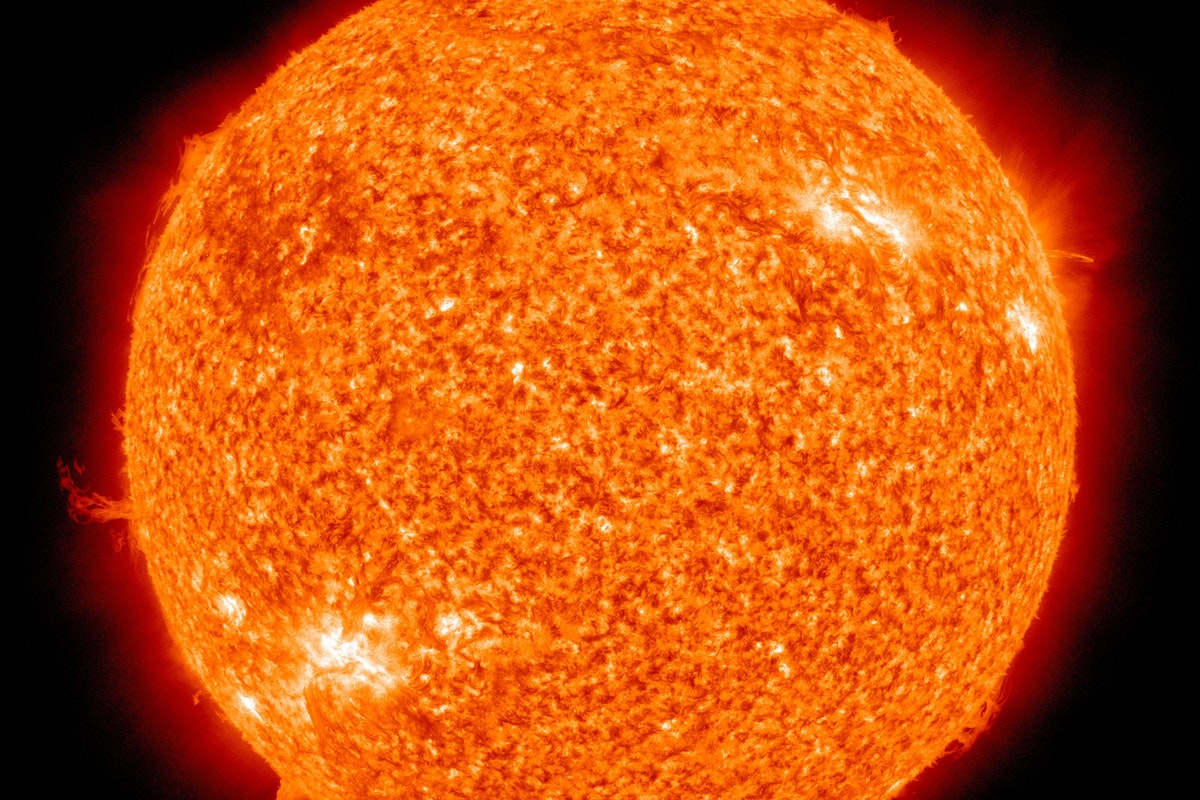

art as a gorged star: eight erasure poems

by Tyler Friend

These are erasures of a book published by MOMA, which features transcribed versions of three lectures given in the 50’s and early 60’s

Visual Art: “Firsts” Video Project

This gallery is in answer to Hunger Mountain‘s open call for one-minute videos addressing the notion of First Experiences. We asked artists to interpret this notion in the broadest possible terms. Here is an assorted and provocative sampling of what we received: Nike air jordan Sneakers | NIKE HOMME

Wonderland:

Readings by Matthew Dickman

“It seems like everyday now, anytime we make art, or really listen to someone else’s point of view, or empathize with the other, that it’s a fight against meanness…”

A Poetry Reading

from Tom Paine

3 Poems from Tom Paine

Didi Jackson Reads

“On the Death of my Father”

His outsider art graces the album cover of Little Creatures

by the Talking Heads, and a vision of his dead

sister climbing down from Heaven

Alison Prine Reads

“Coming Out”

Alison’s poem, Coming Out, is featured in Hunger Mountain 21: Masked/Unmasked on sale now.

How (And Why) to Build an Author Website

by Adam Robinson

Ultimately, don’t be afraid to fail, don’t be afraid to ask for help, and don’t be afraid to simplify, simplify, simplify. Computer people call this “iterating,” as in “let’s iterate on the simplest minimum viable product.”

DIY—Are You a Real Writer?

Amy Souza

Of all my internal struggles, one I really hate has to do with self-publishing. The true me, the one hiding deep down, has never understood why publishing your own work is seen as controversial, vain, worthy of mockery. The socialized me, the one I fight with regularly, buys into the idea that it’s not a legitimate option for “real” writers.

Keep Calm and Query On

Luke Reynolds

Query Letters: Reflections on Bulldozing Writing Walls Now that my wife, Jennifer, and I have been living in York, England for six months, some of the immediate gratifications of moving abroad have worn off. Instead, the steady monotony of life, raising a toddler, and writing have settled in, and I find Winston Churchill’s slogan during… Continue reading Keep Calm and Query On

Luke Reynolds

Why I Have Hemingway Tattooed on My Forearm

David G. Pratt

“Why do you have tattoos?” I often hear.

“Because I like tattoos,” I say.

Some people understand. Some don’t. And some don’t like it…

Memories of Mr. Myers

We asked writers, editors, and educators to remember Walter Dean Myers, the author of more than 100 books, whose profound contributions to children’s literature go well beyond the printed word.

Write Hard, Die Free: Searching for a Mentor and Finding Bob

Kevin Fedarko

Early in my career, lusting as I was to become a literary light in the nonfiction world, I realized that I desperately needed the services of a mentor. I imagined a sort of a cross between an Oxford don, a Jesuit spiritual advisor, and Dr. Phil – an uber-mentor in my mind’s eye. I pictured this person in very specific terms.

7 Deadly Sins of the Writing Life: Introduction

Cheryl Wilder with Suzanne Farrell Smith

Sin. Such a little word. Our lips are drawn together as the hiss of s escapes the lungs, struggling between teeth and tongue through friction. Ssss—the serpent’s sound.

7 Deadly Sins of the Writing Life: Envy

Suzanne Farrell Smith with Cheryl Wilder

Suzanne Farrell Smith shows us her green-eyed monster and wants us to hold a mirror to ours.

7 Deadly Sins of the Writing Life: Sloth

Cheryl Wilder

Sloth, real Sloth, is easy to recognize. Greasy hair, potato chip crumbles down the shirt, dirty dishes stacked at the sink and on the coffee table.

7 Deadly Sins of the Writing Life: Lust

Suzanne Farrell Smith

There are days when I so badly want to write, that I think I could put my infant son in his crib, close the nursery door, and let him wile away the day so I could surrender to my urge. I don’t. Of course I don’t. But sometimes I think I could.

7 Deadly Sins of the Writing Life: Gluttony

Cheryl Wilder with Suzanne Farrell Smith

While studying poetry as an undergraduate in UNC Wilmington’s Creative Writing program, I became obsessed with line breaks. I marveled at how the decision to move a word from one line to the next created suspense and anticipation in the poem. I was in love.

7 Deadly Sins of the Writing Life: Greed

Suzanne Farrell Smith with Cheryl Wilder

“Greed” comes easy to the tongue. Elizabeth Warren spoke at the Democratic National Convention about decades-old “corrosive Greed” reincarnated today in billionaires with Cayman Islands tax shelters.

7 Deadly Sins of the Writing Life: Wrath

Suzanne Farrell Smith with Cheryl Wilder

Wrath doesn’t sound fierce enough for its meaning. It starts with a liquid consonant and ends with a breeze through the teeth, and it’s comprised of a single syllable that contains the first vowel sound we teach to children.

7 Deadly Sins of the Writing Life: Pride

Cheryl Wilder with Suzanne Farrell Smith

I needed to be heard.

I was in the fifth grade in 1984, when missing children—almost always dead children—stared at me from the milk carton as I ate my breakfast.

22 Questions For Poets

Bruce Smith

1. The donée is the unasked for, the inescapable thing that is given to

you. For Lowell it was history, for Berryman it was the Freudian myth of

the Id, for Hughes it was forms of blackness, for Dickinson it was

devotion and skepticism. What is your donée?

Ten Rules For Writers (and an encouragement)

Bruce Smith

1. Poems – lingering and leaping.

I imagine twelve poems of depth and vision, beautiful shapes and

astonishing revisions. One assigned poem that will break us into a kind

of sobbing joy. There are no assignments, per se, but the Exemplars are

there to be used as music to play towards.

Literary & Laundry To Do List #15

Paul Lisicky

Finish storm cleanup. Wipe slop from porch, shovel up mush of leaves. Wash windows a third time. Sweep walk. Pick up torn shingles, torn papers, loose plastic. Hose off white table to make it white again. Stop thinking about the fact that you now live in a part of the country where there can… Continue reading Literary & Laundry To Do List #15

Paul Lisicky

The Menagerie’s Menagerie

Pam Houston

There are twenty-one dog toys on my living room floor because William, my four-month-old Irish Wolfhound puppy, is a hoarder. His much older brother, eight-year-old Fenton, stopped caring about toys long ago and has left many of them to fade in the yard under the yearly feet and feet of snow…