I imagine it’s what breasts feel like

welling up, except this was in my ears

and the tiny roots of my hair,

Author: Miciah Bay Gault

Miciah Bay Gault is the editor of Hunger Mountain at Vermont College of Fine Arts. She's also a writer, and her fiction and essays have appeared in Tin House, The Sun Magazine, The Southern Review, and other fine journals. She lives in Montpelier, Vermont with her husband and children.

Three Poems

The Popinjays Die Lightly

Caroline Misner

Three days. It’s been three days now and people are starting to ask questions. David Jones is no longer a name on an attendance sheet; he’s no longer a member of the computer club; he’s no longer one of the blank-faced rabble that pass through the corridors of Hederton High in preparation for a lifetime of obscurity.

Ballpoints/Homecoming

W.M. Lobko

First week of school all my pens clench up.

Faulty by the boxful, snapped pencil points.

What few words there are are warped.

Two Poems

Sally Rosen Kindred

This was back when meaning was trapped

in pebbled covers the color of his suit.

This was back when meaning

was the engine up the drive…

Missing the Illusion of One

Sara Michas-Martin

Hello internal assembly team.

I am un-singular today in this rash of faces.

I sense the careful in me trolling.

An itch welling at the crown.

Visiting with Robin Black

by Claire Guyton

What’s your best “This is how I got that idea” anecdote? In my collection If I Loved You I Would Tell You This, there’s a long story called “The History of the World,” which is about sixty-five-year-old twins on a celebratory (sort of celebratory) holiday in Italy. He has significant trouble with word retrieval, so… Continue reading Visiting with Robin Black

by Claire Guyton

The Potential of the Peripheral: Secondary Characters in Jane Smiley’s The Age of Grief

by Robin Black

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#339999′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”] INTRODUCTION1 Some years ago, toward the end of an hour-long class during which a group was workshopping one of my stories, someone in the room said, “I was just wondering, don’t these people ever run into anyone else? Don’t… Continue reading The Potential of the Peripheral: Secondary Characters in Jane Smiley’s The Age of Grief

by Robin Black

Three Poems

Sarah Stanton

I’d tear the ceiling from the sky

to grow taller; dove-tail,

pigeon-tail and rip its bonnet

smaller…

Fossiliferous

Nancy Lord

I wasn’t crazy about the height. There we were, one paleontologist who might have been a mountain goat, his two assistants, and me, scrabbling up a mountainside of tilted and crumbling rock strata—or what my companions called “bedding planes.” Loose gravel and rock dislodged by our feet bounced all the way to the glint of streambed in the canyon’s crease below.

The Rivals

Sayantani DasGupta

There is blood all over the battlefield, the broken bodies of warriors and weapons. Spirit shadows rise like mist from the ground, and among the fallen soldiers rides Yama, the god of death, upon his mighty buffalo. Dark as a rain-cloud, with eyes of burning flames, he brandishes a noose and spear in two of his four hands. Newborn babes in Bharat are never given names too early, lest Yama call them to him. And until they are old enough to protest, mothers mar the cheeks of their sons with black spots of kajol, so that the god of death is not tempted by their beauty.

The White House

Jennifer Wolf Kam

Amarilla Sarah Weathersby was not one to have her feathers ruffled. The grown-ups in her life said this time and again and so most of them steered clear of her feathers. The girls, however, did not—those dreadful girls at The Preakney School, Julianna Mattheson, Gwendolyn Goddfrey and the rest, with their whispers and giggles and sideways glances at the lunch table.

Two Poems

Michael David Madonick

My wife does not believe me, in fact

she has started to mock me, to register

in her discourse and demeanor a kind of

flippant disregard for my sincerity…

Back Porch, Twilight

Murray Silverstein

Back porch, twilight, garden on its late-summer binge.

Striders all over the pond. My mother called them Jesus bugs.

They don’t, though, walk so much as land, dimple-&-drift

on water, give it—you can almost hear—a sideways thwack…

The Herd

David Starkey

What is it about my seaside town

ninety miles north of LA

a chattering of starlings, a labor of moles

that makes the washed-up celebrities

who have washed up here…

Story Water

Sayantani DasGupta

Gather ‘round, children, and I will tell you a story.

It is a familiar scene. The storyteller is a village elder, or a grandmother, or a wandering minstrel. The passel of eager-eyed children, and perhaps some adults, sit close. It is the still evening, under the fluttering mosquito-net; or perhaps mid-day, in the shade of an old acacia tree; or a darkening and cold afternoon, by the light of a roaring fire.

Visiting with Elizabeth Gonzalez

by Jodi Paloni

Hunger Mountain interviews author Elizabeth Gonzalez about her prize-winning short story “The Speed of Sound” and asks her question about her processes and philosophies when it comes to writing.

“In my experience, writing “rules” are dull knives.”

Visiting with Donald Quist

by Jodi Paloni

What inspired your story “The Ghosts of Takahiro Ōkyo”? “The Ghosts of Takahiro Ōkyo” came out of nowhere, and everywhere. I think of it as an attempt by my brain to pull together and make sense of a bunch of disassociated ideas I had at the time. I didn’t set out to write a story… Continue reading Visiting with Donald Quist

by Jodi Paloni

Corn Maze

Pam Houston

When I was four years old, my father lost his job. We were living in Trenton, New Jersey at the time, where he had lived most of his life. With no college education, he had worked his way up to the position of controller at a Transamerica-owned manufacturing company called Delavalve. The company restructured itself and dismissed him. My parents decided to use his sudden unemployment as an opportunity to take a vacation, to drive whatever Buick convertible we had at the time from New Jersey to California.

An Excerpt from Marble Boys

Tamara Ellis Smith

From high in the sky, above the pathways of parrots, above cloud lines, above the blue—where the moon and the sun take turns shining over rivers and valleys, oceans and forests, towns and cities and farmlands—from here you can see things.

Flooded with Understanding

Tamara Ellis Smith

Flood water smells old. It smells like something decaying, like something that has been left out for too long, like a mix of oil and compost and mold. Flood silt is heavy. It sticks to everything it touches. A pair of blue jeans covered in it is almost too hard to carry. I know these things.

Sideways Review: Please Eat the Pastrami

by Claire Guyton

I dated a man in college who could not bear to leave food on a plate, his or anyone else’s. He would dispatch his food with good speed, then pick at the borders of my meal while I ate. Before my fork hit the table he’d drag my leftovers to his side and tuck in.

On Material: Writing Prompts

Prompts can be more than just a warm-up to the real writing; they can lead us to material in surprising ways. A dominant left brain can lead to over-thinking, playing it safe, and self-judging—all of which can block the creative right brain. Prompts help us loosen up and let go of control.

Two Poems

Chris Featherman

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#8f2866′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”] These Gifts (Letter to Brooklyn During War) Dear Brian, You’re right: there’s nothing left in war but to believe in a woman with three names who gives me mandarins and to mourn our friends as kings but not kings and… Continue reading Two Poems

Chris Featherman

The Menagerie’s Menagerie

Pam Houston

There are twenty-one dog toys on my living room floor because William, my four-month-old Irish Wolfhound puppy, is a hoarder. His much older brother, eight-year-old Fenton, stopped caring about toys long ago and has left many of them to fade in the yard under the yearly feet and feet of snow…

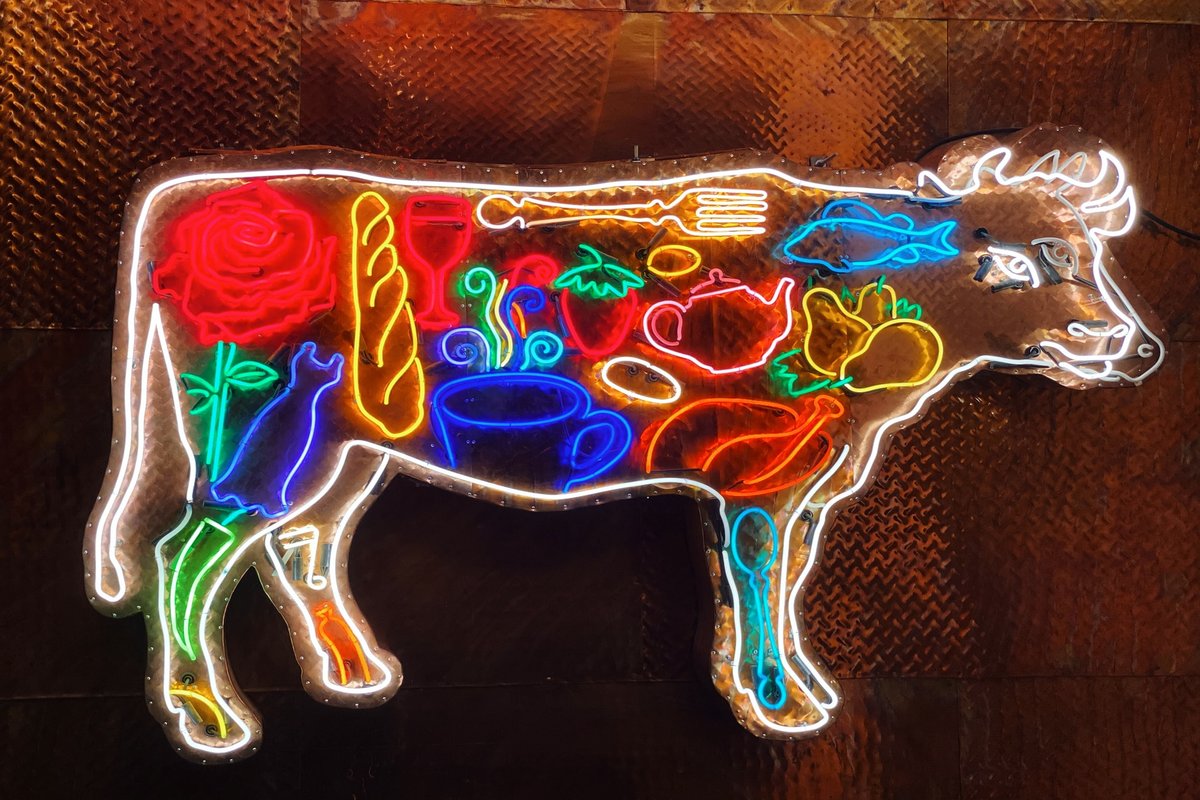

The Bull

Ron Carlson

When they led me

into the China Shop

I didn’t mind,

though it was a bright place

and the wooden floor creaked.

Two Poems

Bradley Harrison

This is the sound of the terror

of isms Of my rickshaw heart beating

yours

Black Bear

Heather E. Goodman

Black bear rouses from hibernation at the end of April when I summon her. She emerges from her den by the cedar grove behind my childhood home in Tower, Minnesota where as teenagers, Mac and I made love. Weary from the long winter, she heads south to the Twin Cities. She cuts through clusters of budding birches under silver moonlight and labors through swampy cattails in honeyed sunrises. She gobbles fronds, catkins, and shoots to feed her empty belly.

The Screaming Divas

Suzanne Kamata

Trudy was riding a city bus, trying not to inhale. The passenger next to her smelled of sweat and garlic. Someone had let out a fart.

Jewel Tones

Samantha Kolber

For twenty-five dollars

my mother can dress your feet

in jewel tones. You send her a check,

she’ll send you jewel tones.

Out on the Bendy Branches

Lindsey Lane

Writing teachers often tell their students to “write what you know” because writers must learn to write clearly and authentically, and the best way to do that is to write about what they know. It’s a place to begin. It’s a place to grow from. It’s a place where we start to hone our facility with craft and voice.

Mad Men and the Writing Life

Sue Eisenfeld

Evening after evening of watching the creative process at work at Mad Men’s Sterling Cooper agency, I began reminiscing about all I had left behind.

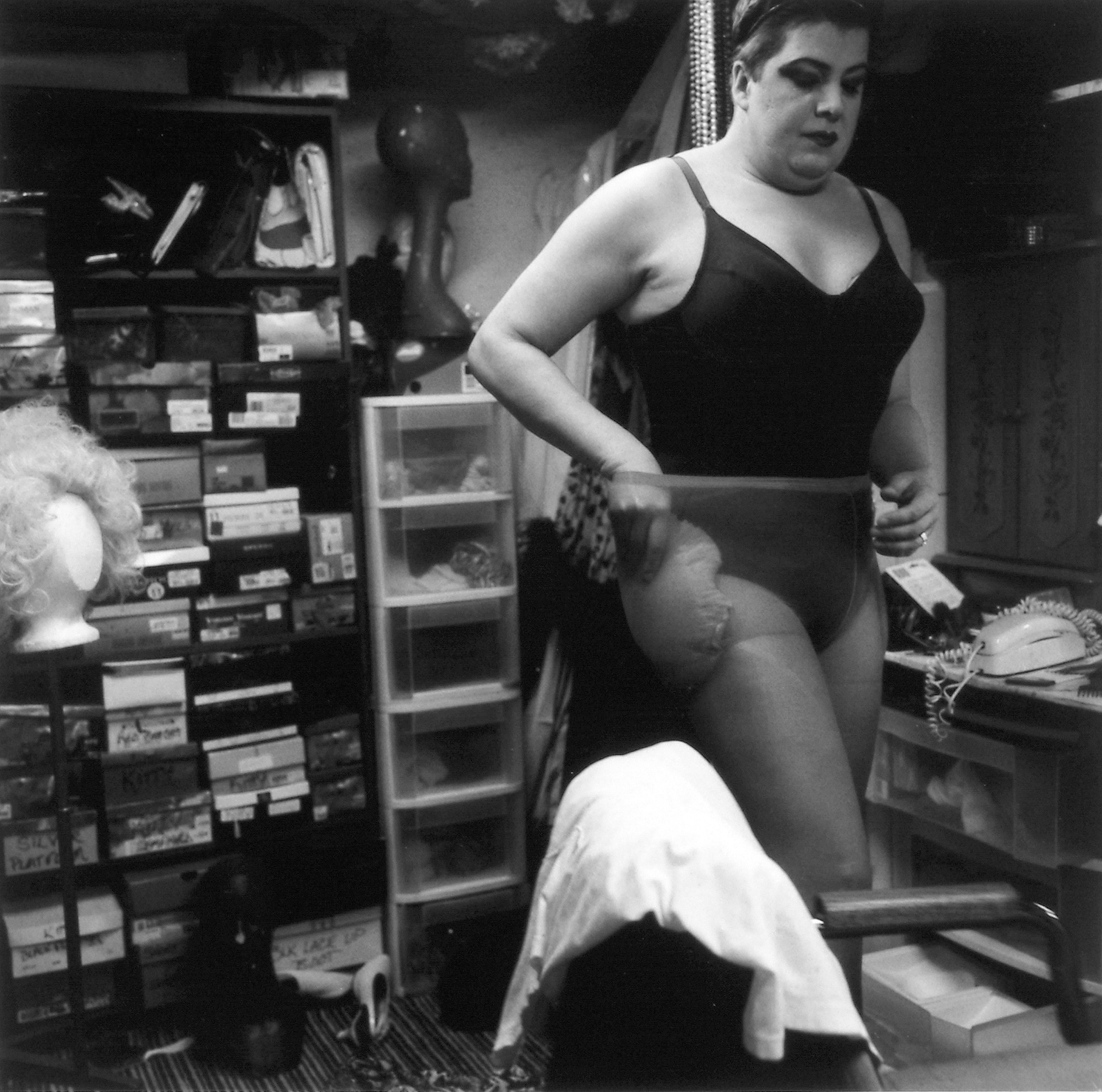

Sideways Review: Her Last Costume

by Claire Guyton

“[T]he instant I decided to retrace the pioneer journey of Laura Ingalls Wilder, I knew I would wear a Laura dress.”

………—from the opening of My Life as Laura

Sideways Review: One Perfect Sentence

by Claire Guyton

When friends recommend movies I shush them. Because no one—least of all me—can recommend a movie without launching into what it is, exactly, that makes the movie worth seeing.

And I don’t want to know! I don’t!

Three Poems

Guadalupe Garcia McCall

Her long, thin arms

warmed us when the North wind

wheezed, like an old man,

Teaching, Writing, and the Practice of Illusion

Can we talk, not to be grandiose or anything, about truth? I don’t mean the kind of truth John Ruskin went on about in his architectural critiques, decrying flexible tracery as barbaric and making fearless leaps between such judgments and the virtue and enlightenment of man. Which pretty much, I would like to point out,… Continue reading Teaching, Writing, and the Practice of Illusion

Writing from Both Sides of the Brain

As writers, we spend a lot of time seeking the shy, elusive muse or avoiding the judgmental, overbearing inner critic. Julia Cameron, author of The Artist’s Way, calls her inner critic Nigel. She writes, “Like my Nigel, everyone’s critic has doubts, second thoughts, third thoughts. The critic analyzes everything to the point of extinction. Everything must always be groomed and manicured. Everything must measure up to some mysterious and elusive standard.”

Idiosyncratic Tone in the Novel

My novel is set in a time and place—1850’s west—that’s already solidly ingrained into the American consciousness as a mostly historically inaccurate and over-dramatized milieu. For three years, I spent enormous energy creating the historical details—believable characters, a rich sense of place, credible plot. All this realism came at a cost. My novel was missing… Continue reading Idiosyncratic Tone in the Novel

The Perks of Being Bipolar

Bobbie Pyron

Recently, I spoke at a benefit event I’d put together for my local animal rescue organization. I’d brought together five authors (including myself) who all wrote about and were inspired by their love for dogs. I told the audience how the idea burst into my mind two months before my book, A Dog’s Way Home, was due to be released.

The Stage Manager

Jennifer R. Hubbard

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#33999′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”] My father would not get out of bed. Well, he did sometimes, usually to go to the bathroom, but other than that, he pretty much lived in bed. Although he didn’t get up, he moved around a lot. Sometimes he’d… Continue reading The Stage Manager

Jennifer R. Hubbard

On Rhythm: In Sentences

Rhythm is the foundation of good riding. Clint McCown told me, “The difference between bad writing and good writing is rhythm.” If I can control a horse’s rhythm, surely I can wrangle nouns and verbs.

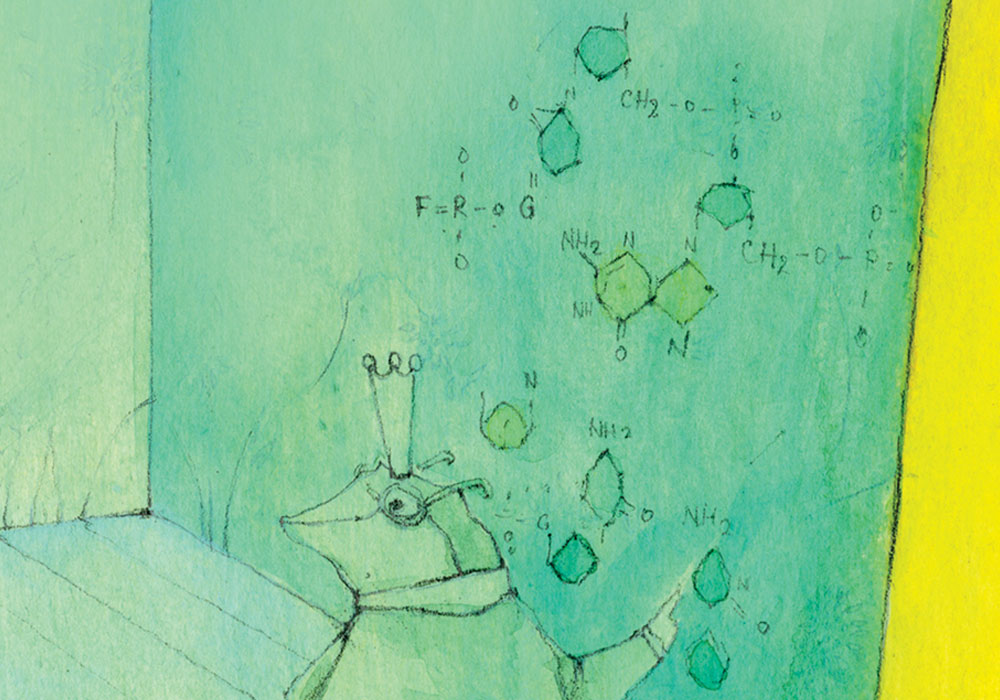

On Poetry: Sine Waves

I’ve found that many contemporary lyric poems—though certainly not all—make interwoven use of three distinct elements: image, narrative, and rhetoric. Sometimes I think of the interaction between and amongst these elements as representing a sine wave or sinusoid. A sine wave looks like a regularized horizon of hills and valleys: first a hill, then a… Continue reading On Poetry: Sine Waves

The Violin

Jennifer R. Hubbard

It was April and all Monticello was stirring, but in their cabin

Mama had just put baby Maddy down to sleep and she told

Beverly and Harriet to be still. Beverly did not want to be still.

The Best Ideas

Emily Pulfer-Terino

We’ve said desire requires absence.

We’ve said a lot, the good wine gone,

light draining. Outside, pavement dizzy

I Craft, Therefore I Am: Creating Persona through Syntax and Style

Persona is the mask writers wear in their novels, short stories, poems, essays and memoirs. It is the artfully crafted or created “self” on the page. Poet Ezra Pound defined persona as a literary stand-in for the author’s voice. It is not the actual self or author; real lives can rarely be contained within the margins.

Another Visit with Deborah Vlock

by Claire Guyton

For me, it’s probably harder to make someone laugh – I’m not, alas, a very funny person. Although I’ve lately been writing darkly humorous stories, my typical mode is fairly serious, even heavy. At heart I’m a pretty emotional person, and I like to evoke emotions – including levity, but also anxiety, sadness, […]

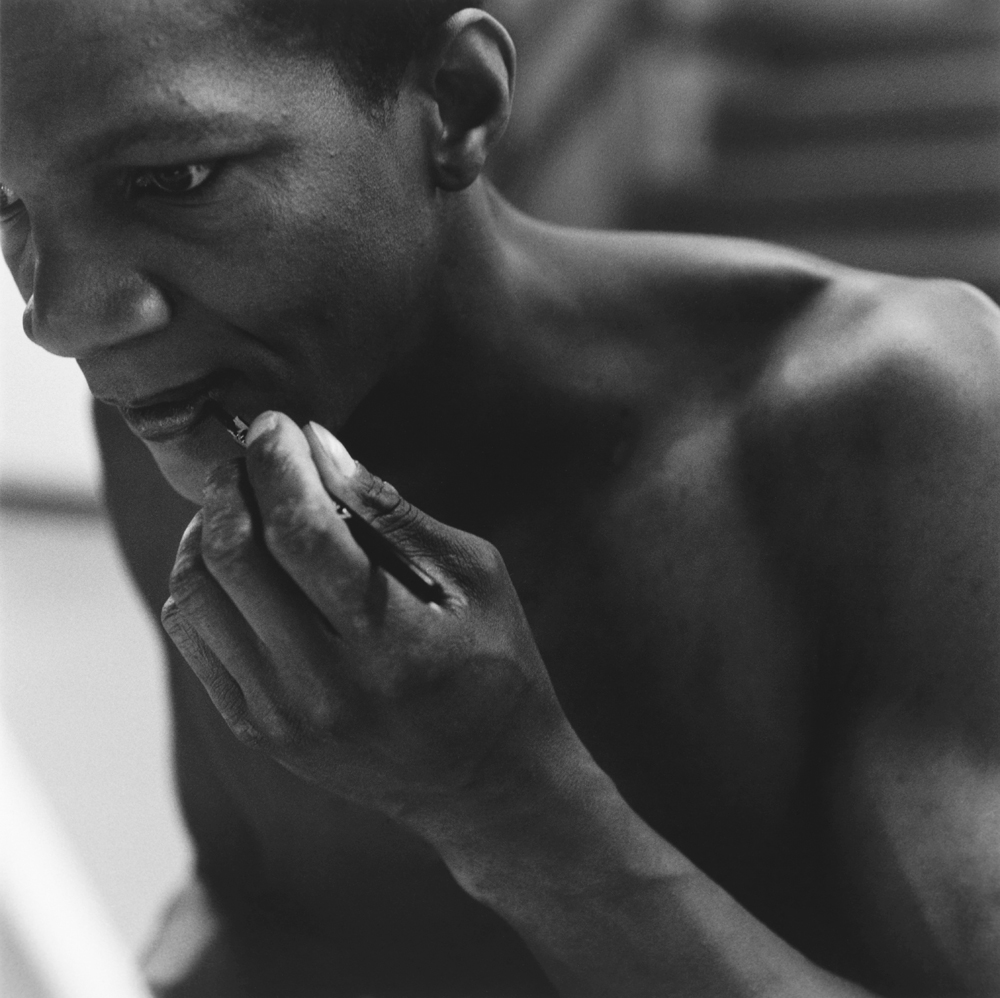

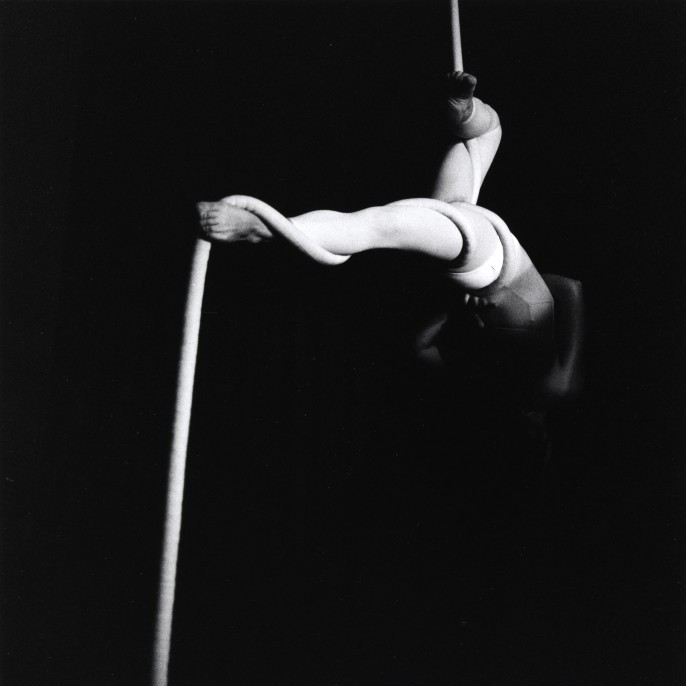

What More Can a Body Do?

Charisse Coleman

You are in training, learning how to help people with the sorrows, fears, and angers they want to banish, the pains they wish to exorcise or learn to carry more lightly. You are introduced to a man with cancer. He is exactly your age. Forty-eight. The first time you meet is the second week of your internship as a clinical mental health counselor.

Visiting with Heather Sharfeddin

by Claire Guyton

What’s your best “that’s how I got that novel idea” anecdote? I often go to the cemetery to think (not any one in particular, just whatever is convenient). A cemetery is a place where you can curse, talk aloud or cry, and no one asks if you need help. Once, while I was mulling the… Continue reading Visiting with Heather Sharfeddin

by Claire Guyton

The Happy Ending Effect

Why do I write? Considering the odds of publishing, we have all asked ourselves that question at one time or another. If we haven’t, we should. When I set out to write a novel some ten or more years ago, I had a grand vision in mind, in which I would hit the New York… Continue reading The Happy Ending Effect

When Elijah Pritchett Goes to the Gym

Julie Marie Wade

I sometimes go with him, & so does our friend James.

I joke it is like a “mind gym,” but not in the cultish, self-help sense of the phrase.

Quarry

Kevin Waltman

Be nice. That’s the second rule. Even when they’re being assholes, or putting you down, or leering at some other girl—be nice. That’s Gospel, according to Janice, who hasn’t been a virgin for a year and a half now, because there’s nothing guys dislike more, she says, than a disagreeable girl.

Death by Pufferfish

Mayumi Shimose Poe

Kazuo Ikeda’s first and last taste of fugu had been the spring he turned seventeen. Seventeen was practically adulthood. Kazuo’s goals for his adult self were: 1. Do something interesting. This did not include camping in the car amongst redwoods with his parents; eating salted toffee while visiting historic Old Sacramento and nearly as historic old relatives; or catching the cable car to Fisherman’s Wharf only to end up overstuffed at Ghiradelli Square.

Stone Field

Christy Lenzi

I’m a loaded gun.

Henry knows. He thinks he and Jesus can save me from myself.

Visiting with Mayumi Shimose Poe

by Claire Guyton

Boredom, a restaurant review, and San Francisco airport. In spring 2008, my husband Dave and I had a really early morning flight out of SFO. At the time, he worked at the airport as a Flight Operations Officer for JAL. He worked the night before we left, so I tagged along with him so we could go straight from the office to the gate.

Monsters

Jennifer R. Hubbard

In her Young Adult piece, “Monsters”, Jennifer R. Hubbard looks at the different types of “monsterhood” in the world and what it’s like to live like one: “There are other monsters. So many, and of so many different types, that sometimes I wonder who draws the line between monster and non-monster.”

The Proposal

Lindsey Lane

Marshall steers the lumbering station wagon past the edge of the pull-out behind the cactus and scrub cedar. He turns off the car and opens the windows. He knows no one can see his car tucked back here. Especially at twilight. It’s like the gathering shadows swallow him.

Snow, For Instance

Austen Rosenfeld

This day is like a painting

hung

a little too far to the right

or to the left. Step back.

Nocturne

Karen Munro

I went home with a woman from the bar, which is something I never do. She had black hair with a long streak of grey in it, and I thought she looked tragic and romantic. She reminded me of my aunt Dolorosa, who grew a grey streak after all her stargazers died at once.

When Cody Told Me He Loves Me on a Weird Winter Day

Liz Prato

Cody and I are sitting side-by-side on a picnic table, looking toward the Rocky Mountains covered by ponchos of snow. Black-necked geese are honking, and I’m thinking, They must be lost. They shouldn’t be in Denver. They should be in Acapulco.

Lovebird

Carolyn Walker

It is autumn and the leaves of October have begun to fall, but still Jennifer’s summer romance blossoms with a freshness that even the first cherry trees of April might envy. Her boyfriend David, who is trapped in his body like a mummy in its sarcophagus, calls her almost every day.

Self-Portrait #21

Denise Bergman

All evening my tongue

a manic magician in a submerged metal trunk

unknotting constraint.

Sure

Jean Esteve

The sun that succumbed to the mudflats

some time around four in midwinter

was blue as an owl and now its power

to rouse us is gone, gone, like the nuclear

end-of-the-world. I’m glad you were sure.

Two Poems

Phillip B. Williams

Built up only to collapse—your body over mine, into

mine, a hollow pentacle easily fallen into disrepair:

your tip still spilling as my body did drink.

The Slug

Karen Holmberg

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#8f2866′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”] ………It glides by with the grand leisure of a whale in migration. Yet once it sees me ………it retires, melts a little ………………foreskin over . ………its face. The prompt eyes probe upward and re-bloom, dewed with humectants. I stroke its… Continue reading The Slug

Karen Holmberg

Soul Food

Ginny MacKenzie

You pull into a diner and order your life

to change. On the road

you saw farmhouses

with stacks of frayed hay

The Kneebone Boy: Excerpts from a Novel

Ellen Potter

There were three of them. Otto was the oldest, and the oddest. Then there was Lucia, who wished something interesting would happen. Last of all was Max, who always thought he knew better. They lived in a small town in England called Little Tunks. There is no Big Tunks. One Tunks was more than enough for everyone.

Espionage Is a Risk

Amanda Skelton

Each tread of the staircase in our rented apartment measures roughly nine inches. The risers are eight inches high. Builders use various formulae (e.g. height plus depth equals seventeen) to fix the tread/riser ratio. I use a formula—the word “recipe” seems overgenerous—to prepare the protein shake I carry upstairs, five times a day, to my twelve-year old son.

Worm Apples

Jeffrey Boyer

I sit in my parlor with the man on the phonograph.

“Can you help me find a policeman?” The man on the phonograph speaks like there is no danger. “Konnen sie mir helfen polizisten zu finden?”

Ode to Wilmington

Jeff Tigchelaar

Wilmington, Delaware; Wilmington, Delaware.

Does any real mail

ever come from there?

Here There Be Dragons

J.D. Lewis

Here is what I like to think happens when we die: first, we float. Alone in boundless blackness, we are conscious only of absence. Then, all around us, faint pinpoints of light brighten slowly, imperceptibly, so we don’t notice until we’re surrounded.

Mom Says

Liz N. Clift

Summer was going to be perfect:

the mall, the beach, the computer,

no Kevin whenever he was at camp,

which was all but one week this summer.

The Race

Rachel Furey

“Unbelievable,” Mr. Wortz said, holding my twin sister’s file in one hand and mine in the other. He set them both down on the desk and ran a hand through his beard.

The Eve of St. Agnes

Margaret Nevinski

I hop out of bed and pull open the blinds. Snow. Thick flakes fall onto the backyard topiary that’s Mom’s masterpiece. About five inches on the elephant’s head. Not enough to call off school. I slip past my parents’ door to the kitchen and grind my organic Kenyan coffee beans. Wonderful, everyday normalcy.

Wings

Jennifer DeMotta

The stones would skim across the water, hopping lightly, like rabbits. The record was five hops before the stone sunk. When we got bored with that we went swimming in the lake to cool off until our bodies turned into wrinkled old prunes and we had to lie in the sun to plump back out.

Hornworms

Angelica Jackson

The fat body of a hornworm hit my pail and Elsie dashed to catch up. I don’t know why she was rushing; it’s not like there weren’t plenty to go around. Each plant was alive with hungry mouths tearing at the leaves; the ground was littered with the dark pellets that come out the other end.

A Sister’s Story

Jenny Hubbard

Where was I when it happened? Like a lot of kids, I was in a classroom watching the clock with its slow, indifferent hands. It was almost time for lunch, and no one was paying attention to Mr. Maynard, who was trying to teach us about fault lines.

Three Birds of South Africa

Steve Myers

An early blessing—

neither “the image of Industry

in winter,” nor “flashing seraph,”

but pure figure

Trucker’s Lament

Casey Thayer

Loneliness needles him like a ghost limb

on Sunday nights, so he porch-sits.

He cracks the tab from a can of Bud,

scans the valley’s gallery of streetlights.

Pantala flavescens

Marie Gauthier

Day’s close—August’s ineluctable heat

avows rain, relief. Above the new-mown

meadow, an aria of wings:

the swarm strafes gold.

Ota Benga in the Land of the Dead

David Yost

Ota Benga, flecked with shadow and besmeared with elephant dung, crouches at the base of a zebrawood tree. He hears branches crashing down, liana tearing free of the canopy, and then his prey shoulders past: the elephant, the meat that walks like a hill.

Dialogue

Deborah Vlock

Ute Schmidt’s first lesson, upon arriving in Boston, is that Americans talk fast and laugh at things that are not funny. She learns this while going through customs and immigration at Logan airport, when an officer asks her where she is hiding the sausages and then laughs immoderately.

Descent

Frank Paino

Early December and the moon bloats with milky light.

Hyde Park sleeps, silvered in ice that wraps the naked elms—

all the lampposts and curved benches. Inside her, heaviness

like the thick silt and mud on the Serpentine’s bottom.

Burial

Jessica Ratigan

We walked down to the water together

the day his old friend just didn’t wake up.

I had no words to offer as we sat in the sand

watching the mother osprey hunt.

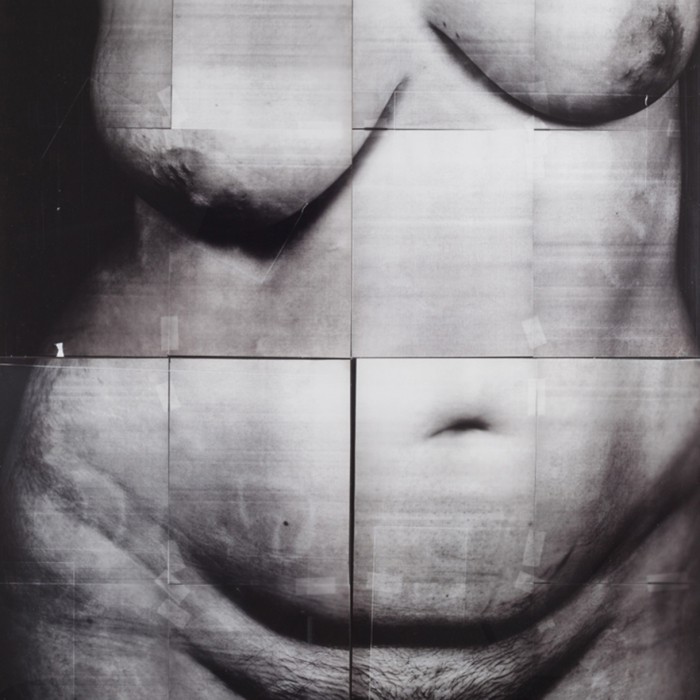

Belly

Lauren Goodwin Slaughter

I’m tired, she says. We’re sleeping, he says.

Who knew a beginning could be totally quiet.

Bones in the Cellar

Cheryl Spanos

Finn’s baggy trousers hadn’t been able to hide his trembling knees. But no one called an O’Reilly a coward. Finn had bristled and accepted the challenge. Wherever Finn went, Ida followed. She’d had to accept the dare, too. Family honor depended on it.

Cloud of Witnesses

Jane Hertenstein

“Watch out now, Granny.”

I had a sheet of wrapping paper spread across the living room floor. It was Christmas Eve and I was busy wrapping up a present for Mama.

Tell Me a Secret

Holly Cupala

It’s tough, living in the shadow of a dead girl. It’s like living at the foot of a mountain blocking out the sun, and no one ever thinks to say, “Damn, that mountain is big.” Or, “Wonder what’s on the other side?” It’s just something we live with, so big we hardly notice it’s there. Not even when it’s crushing us under its terrible weight.

Definition

Kerrin McCadden

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#8f2866′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”] I once found a deer collapsed near a lake—sleek, immaculate, & unmoving except for its antlers, which swarmed with orange-&-black-speckled butterflies that obliterated the velvet beneath. Whatever word explains this, I don’t want to know it yet. —Matt Donovan The… Continue reading Definition

Kerrin McCadden

Vultures

Shane Joaquín Jiménez

The kid crouched behind the chuparosas along the ridge. Down in the valley, the man stoked the fire with a long, crooked sage switch. The kid imagined that he felt the outer warmth of the fire, but the desert cold coiled cruel and true inside his bones.

Visiting with Natalie Serber

by Claire Guyton

What inspired your story “Shout Her Lovely Name”? Fear. All that can go wrong and how to make sense of it. All writers have favorite words we have to guard against over-using. What are yours? Any words to do with dental hygiene. I don’t know why, but it seems dental care is my default mode.… Continue reading Visiting with Natalie Serber

by Claire Guyton

Triumph

Chris Haven

Snow was coming down hard, better than an inch an hour according to the radio. Ed Wilson’s wife Winnie had gone to dinner with friends from the non-profit where she volunteered, unaware that the worst blizzard of the decade was blowing in.

Orchid

Erika L. Sánchez

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#8f2866′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”] Woman’s destiny is to be wanton, like the bitch, the she-wolf; she must belong to all who claim her. — Marquis de Sade In Cicero the white prostitutes in front of the Cove Motel lean into cars— knotted hair, limp… Continue reading Orchid

Erika L. Sánchez

Our Own Version of Iowa

Richard Adams Carey

It was 1963, but Barney Wetterer said we were living in the Year One, A.B.—After Bonnie. It was still less than a year since the Sprinkles had moved in, and Barney had the day he first saw Mrs. Sprinkle circled in red on his calendar.

“We came to visit…”

Gregory Orr

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#8f2866′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”] We came to visit, though You’d died that spring; Came to see, one more time, Your famous, dense garden In all its summer glory. Came to sit under the cedar That shadows the path And read your poems aloud And… Continue reading “We came to visit…”

Gregory Orr

Killing the Rabbit

Amber Flora Thomas

[av_hr class=’custom’ height=’50’ shadow=’no-shadow’ position=’center’ custom_border=’av-border-fat’ custom_width=’100%’ custom_border_color=’#8f2866′ custom_margin_top=’30px’ custom_margin_bottom=’30px’ icon_select=’no’ custom_icon_color=” icon=’ue808′ font=’entypo-fontello’ admin_preview_bg=”] You have to hit it on the head with a hammer, good and hard between the ears. You will think of hunger, as its tongue preens its wet nose and its legs buck air and its eyes roll back into… Continue reading Killing the Rabbit

Amber Flora Thomas

Living In Sin

Tony Perkins

Lois Fleming and Bob Cuso are ninety-five years old, and they’re not married. It’s a scandal—they’re living in sin.

Champlain

Sarah Cornwell

We stand on the ferry’s top observation deck, I with my binoculars, elbows on the rail, trying to spot Camp Island—the bluff, the dock, the raft—and Rose leaning into the battering wind with closed eyes, savoring some private thought.

A Country Where You Once Lived

Robin Black

It isn’t even a two hour train ride out from London to the village where Jeremy’s daughter and her husband—a man whom Jeremy has never met—have lived for the past three years, but it’s one of those trips that seem to carry you much farther than the time might imply.

Bobby Malone

Clint McCown

Even before he got dropped off at his parents’ house, Bobby Malone had begun to worry. The streets near the square were deserted, and all the streetlamps were out, leaving the familiar neighborhoods in darkness

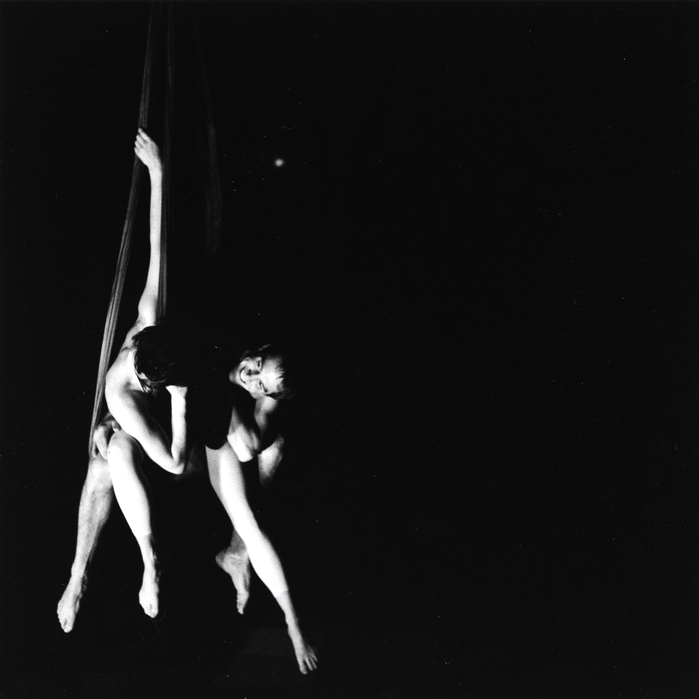

Dissolve

Aimee Pokwatka

When my lips hit the floor, I taste blood and think of kissing. The hardwood is gritty and scuffed from our shoes. I sit up and touch my mouth, find a feather from last night’s magic show. Richard keeps shouting the choreography, slapping his thigh to keep the beat.

Harmonious Earth

John Spaulding

The stars shine tonight /

like lights in vinegar.